x

x

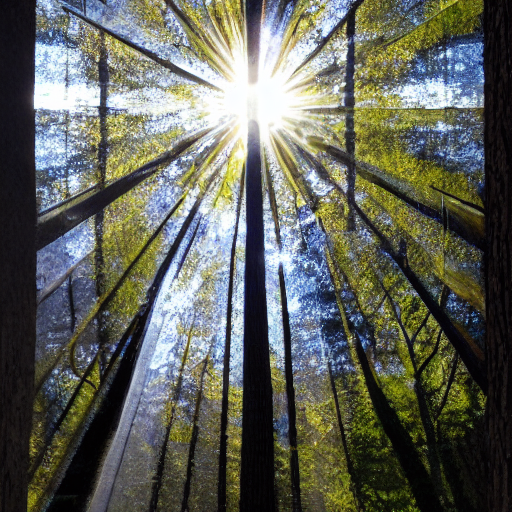

A shaft of sunlight filtered through the treetops, flashing off a dangling mirror. For just an instant Nick Pembroke was blinded by the glare. Then a breeze whispered through the trees. The mirror fluttered, redirecting the ray to the basin of water at his side, and Pembroke put out a steadying hand, smearing shaving cream on the glass. It was just one more of the minor inconveniences when he was on a mission.

Pembroke finished shaving, splashed cool water on his face, and toweled off. While other men trotted about the site in the early morning without shirts, he returned to the tent for his. He was their leader and they expected to see him reappear wearing the khaki short-sleeved shirt with his colonel's eagles on the collar.

He smiled down at Pilar, still sleeping on the raised platform that served as their bed. They were used to better accommodations, but at least the wooden deck was high enough off the ground to keep snakes, scorpions, spiders, and other things off them as they slept. The netting that was their door kept mosquitoes and other airborne insects out if the tent remained darkened at night. As long as Pilar was with him, that was all right with Pembroke.

Colonel Nick Pembroke was the commanding officer of Special Unit Madrid. Each special unit of the VC was named after a revolutionary hero. He wanted to name his group after the Costa Rican, Juan Rafael Muro, but the Muristas were giving that name a Chinese smell these days. Special Unit Madrid had been trained for months in Ciudad de la Revolución, Cuba, in the art of high-speed coastal attacks. The unit was now camped in the hills overlooking Portobelo, a Caribbean coastal town about twenty-five miles northeast of Colon.

Pembroke's strikingly handsome features were the result of the mixture of bloods beginning with his great-grandfather before the turn of the century. The first Nick Pembroke, a determined engineer from New Orleans, arrived in Panama in 1882 from New Orleans, one of five hundred jobless blacks hired to work on the construction of the Panama Canal. In those days white men were the engineers, surveyors, accountants, and paper pushers, and blacks from America's deep south, Jamaica, and other islands, were laborers along with many of the country's Indians.

The French were paying decent wages in the jungles of Panama. The work day was from five-thirty in the morning until six at night, grueling under the hot sun, whenever it shone, and in the oppressive humidity during the eight-month rainy season. There were a multitude of ways to enter the next world before a man's time was up. If the mudslides didn't crush him, he might be bitten by a snake, a scorpion, or a tarantula or attacked by a jaguar. He might also suffer a pain-wracked death as a result of one of the many jungle diseases, though malaria and yellow fever were by far the most common way to die.

Of the five hundred blacks recruited, more than two hundred of them were dead within three months. Another hundred and seventy-five were gone in six months. It seemed obvious to Nick Pembroke that he must be immune to yellow fever, but he had no idea why he failed to contract malaria since there was simply no known immunity to it.

His contract with the company expired at the end of twelve months but, unlike most of the others who purchased tickets from the company to sail back to New Orleans, Pembroke stayed. He knew a black man could expect little in the way of opportunity in Louisiana, but he could be accepted nearly as an equal in this Central American country. There were so many mixtures that natives could trace black, Spanish, Indian, English, Portuguese, or Mayan blood in their heritage. The tall, handsome American Negro was accepted there, especially with the money he'd doubled in poker games and a desire to stay in their country and develop a business.

Nick Pembroke's son, Joseph Pembroke, grew up during a time of significant political upheaval and transformation in the early 20th century. The era was marked by a palpable sense of change as Panama navigated its newly gained independence, confronting a myriad of challenges including entrenched inequality and pervasive corruption. Influenced deeply by his father's legacy of social justice and advocacy, Joseph Pembroke was imbued with a strong sense of purpose and commitment to reform. As he matured, he became increasingly involved in the political landscape, emerging as a fervent advocate for progressive change. Throughout the early 1900s, Joseph engaged actively with various reformist movements that aimed to tackle the systemic issues plaguing the country. His activism was characterized by a relentless pursuit of political and social reforms, as he sought to address the disparities and injustices that affected the lives of many Panamanians. His endeavors to challenge the status quo were met with a mixed response; while he garnered substantial support from those who shared his vision for a more equitable society, he also faced significant opposition from established interests resistant to change. By the 1930s, Joseph Pembroke had firmly established himself as a prominent and influential figure in Panama's political sphere. His alignment with progressive movements, dedicated to addressing the deep-seated social and economic inequalities, positioned him as a key player in the ongoing struggle for reform. His contributions to the political discourse of the time were instrumental in shaping the trajectory of Panama’s socio-political development, reflecting his unwavering commitment to creating a fairer and more just society.

Joseph Pembroke’s son, Eduardo Pembroke, was heavily influenced by the revolutionary fervor of the 1960s. As Panama faced political instability and economic disparities, Eduardo embraced leftist guerrilla movements, inspired by the global wave of revolutionary activity. Eduardo became a key figure in radical leftist circles, advocating for armed struggle against oppressive regimes. His commitment to revolutionary ideals was fueled by a desire to transform Panama into a more equitable society. Eduardo’s actions included sabotage and confrontations with government forces, which earned him a reputation as a relentless revolutionary.

Nick Pembroke Jr., Eduardo’s son, grew up surrounded by the revolutionary zeal of his father. By the 1980s, Panama was experiencing significant political and economic turbulence, and Nick Jr. followed in his father's footsteps, becoming a prominent leader in the leftist guerrilla movement. He adopted a more strategic approach to guerrilla warfare, blending traditional armed struggle with grassroots organizing. His efforts aimed to address systemic corruption and economic inequality. Under his leadership, the movement achieved notable successes but also faced severe government crackdowns. Despite the challenges, Nick Jr. remained a symbol of resistance and hope for those seeking change.

The current Nick Pembroke, born in the early 1990s, grew up amid the lingering legacy of his family’s revolutionary ideals. He had become a natural leader who had developed a hatred for the United States. Despite the formal handover of the Panama Canal and the closure of military bases, the legacy of American intervention and influence in Panama’s history was a source of resentment for Pembroke, a symbol of imperialism and oppression as far as he was concerned. When he was old enough to attend college, he viewed the Americans' departure as insufficient restitution for the past injustices, and saying so attracted followers he needed if he was going to have a part in Panama's future. He refused to follow in his other brother's footsteps and attend an American college. Instead, he chose to stay in his own country and joined the Guardia after a couple of disappointing years at the local university.

With the Americans no longer involved, the government believed that the threats to its sovereignty or the canal were relatively low. The geopolitical landscape had shifted, which led to a perception that a large military was unnecessary. Nick learned that the local security strategy was now based on current assessments of threat levels and regional stability rather than maintaining a large standing army. When he was twenty-five he was chosen to attend a military school in Fortaleza del Pueblo. He was the leader of his class and returned to his country as a proud officer.

Pride also inspired ambition and Nick Pembroke found that too many of the senior officers and the politicians in his country were pleased with what they had once the Canal had been returned to them by the U.S. Yet the people and the countryside beyond the cities were still desperately poor. His dissatisfaction was encouraged by other young men in the military and he became aware of the existence of a group that wanted to improve their country. They thought that only through a new system of government could they achieve their ends. While most rebel organizations failed for lack of money, material, and training, this organization was very much alive because of aid from their Cuban friends. Much of the assistance they received came from men whom Nick had known during his years in Fortaleza del Pueblo. They wanted to help and claimed that in twenty years the countries in the Caribbean littoral could be united much like the European Union, or the Americans to the north who were their enemy.

Pembroke rose to become a colonel very rapidly because of his natural leadership instincts. Almost before he was aware of it, he was looked upon as a critical factor in the major drive to give President Arosemana that they could appear in any part of the country and secure ports, cities, and even airports for as long as they wished. Once the people understood their power, Arosemana would listen.

The raid on Colon was planned, then, for the benefit of the people. They would see the government of the second largest city in the country in the hands of rebel forces for as long as twelve hours. What the Panamanian military didn't suspect was the naval effort that had been planned. The shock effect of an attack from the sea would send the army in the opposition direction. This was just what Fortaleza del Pueblo and a number of his counterparts for special schooling in high-speed boats earlier that year in Ciudad de la Revolución.

Pembroke strolled to the edge of the clearing and looked down the slopes through the heavy undergrowth to the town of Portobelo. It was a sleepy little place at the end of a harbor that faced to the west, a peninsula to the north protecting Portobelo's anchorage and piers from the damaging Caribbean "northers." Although the morning sun sparkled on sloped metal or red-tile roofs, it was still too early for the streets to be bustling. And since there were no major highways into Portobelo---her major commerce was fishing---the people were left to go their own quiet, poor way.

Only a select few of the natives realized that the nearby jungle, reaching the water's edge along the harbor, concealed high-speed attack craft. Some were large Chinese-made hydrofoils delivered only a few years ago to the Cubans. Others were conventional guided missile boats, heavily armed and dangerous. Skeleton crews lived aboard them, and today Pembroke and his men would join them for the attack on Colon. Rebel spies had leaked just enough word for the government to expect a land attack. A thrust from the sea would make an unforgettable impression.

"Nicolas....Nicolas." Pilar was striding toward him. Few people spoke to him by anything other than his military title. Only those who were very close called him Nicolas. That he bore an American surname was difficult enough for them to accept, but Nick's first name was too much. To them he was Nicolas.

He smiled as Pilar approached. Somehow she looked attractive even in the khaki military outfit she preferred. I couldn't have done much better, he thought to himself. The only other woman he'd ever cared for was the student he knew when he'd turned twenty, Catalina Cato. But she'd run counter to what he believed in and gone to the United States for her education. When she came home, she involved herself in the system he hated, and any relationship they might have had was lost. But he would never shake her memory.

"Nicolas, why didn't you wake me up? I might have slept there all day." But she was smiling as she chided him, and he smiled back.

"No, you wouldn't, not today. I'm surprised you weren't awake before me. You're usually the one sounding reveille." Looking all around him, he saw the camp following a well-established routine. Special Unit Madrid had constructed this simple camp months before, in anticipation of this raid. Sites had been selected by the leaders at the suggestion of their Cuban advisors, and planning was all-important. Logistics demanded an equivalent effort. Successful battles were won by proper, detailed planning and the selection of and replacement of necessary supplies well beforehand. He realized his Cuban friends had likely been taught that by their Chinese mentors. Pembroke hated the Chinese almost as much as the Americans---but still, they needed the Chinese.

"I heard movement around camp," she answered. "And the food." She sniffed the air tentatively, recognizing the odors emanating from the mess tent. "The coffee and bacon are reveille for me."

"Come on," he said, motioning her towards the source of the pleasant aromas. "Let's have some breakfast. It's the last square meal you'll get for a while." He insisted on maintaining a discrete distance from Pilar outside of his tent. There was no point in holding over his men's hands the fact that his woman traveled with him while so many were by themselves.88Please respect copyright.PENANAqDbSu3yuQc