x

x

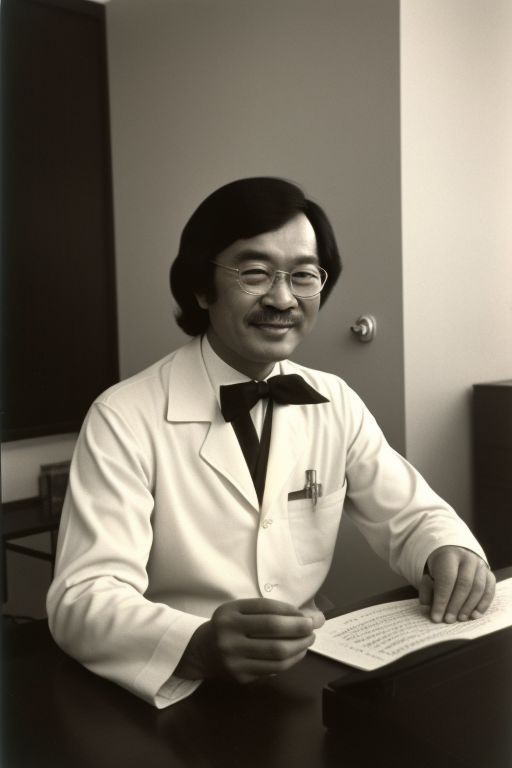

Dr. Duan Qigang had been nauseated all morning, and he was not sure if it was something he ate, drank, or possibly the nurse he had slept with the night before. Medically, he knew there was no disease he could contract from sexual intercourse whose symptoms of nausea would appear the very next day.

Morally, however, he felt he was being justly punished for not even liking the woman, but rather taking her because he was there, she was there, and both were willing. Somehow, it went better with roses and soft words. And maybe that was why he had drunk too much and eaten too much, to make up for the lack of romance. He wasn't eighteen anymore. He should've had higher standards, he felt.

Unfortunately, this late afternoon at the university hospital complex, he was paying for it, and he could not return to the apartment his embassy had provided him here in Oslo because he was promised to meet an American scientist today who was bringing a specimen.

A good one, he hoped.

"A whole body?" Dr. Duan had asked. "What kind of decomposition was there? None that the Americans could see? In glacial ice? What kind of ice? Where?"

"Do you want it, Dr. Duan?"

"Possibly. And you are?"

"Dr. Kittridge Carson. We met at the conference in Stockholm last year."

"Which one, Doctor? I am part of a Sino-Scandinavian Friendship Pact, so I do make many appearances."

"The one on cryogenic applications to medical problems. Frostbite, if you prefer. You were gearing it somewhat for a lay audience. We were more interested only in how we could immediately save lives."

"Saving lives is never 'only', doctor. I don't seem to place your name."

"I'm sort of tall. Geologist."

"The Texan!"

"Uh, yeah."

And then Dr. Duan remembered; he remembered the Texan because that was what the big American had seemed to be reluctant to divulge last year. When asked where he came from in America, the American had said, "All over." He had studied in Chicago and California; "all over," he said. But where was he born?

"Oh, just a little place in Texas," he'd said, and Dr. Duan until that time had never known there were any negative feelings about people coming from certain parts of America, least of all Texas. The Texans he had met always seemed rather proud of it. Cowboys and all that.

So, feeling somewhat embarrassed by accidentally stressing the one point he'd assumed the American had felt somewhat uneasy about, Dr. Duan had said he would be happy to take the specimen. But he had not mentioned what part of the university complex he would meet him at.

There was his office on the third floor of one building, and the laboratory he shared in the basement of that building, and the hospital itself, which was yet another building. Now, which entrance in which building? Where did one deliver a frozen cadaver?

When confronted by this problem, Dr. Duan tried to remember which air base the American had phoned from, so that he could send more specific directions, instead of the University of Oslo hospital complex. Failing to remember, Dr. Duan prepared to receive a cadaver somewhere.

There were many ways it could be received. A good specimen whose sustained low temperatures had retarded body action could go directly into one of the cryogenic cylinders in the lab to be examined later.

A decomposing corpse, however, was just that, a corpse. That was not his area. The normal body process at normal temperature was to take apart the body and put it back into the life cycle of the earth. A decomposing cadaver would have to be taken to the emergency room of the hospital. There it would be pronounced dead, and proper papers filled out. Dr. Duan expected it would not be a decomposing corpse. The American was a scientist and he should understand the limitations of cryogenics.

Therefore, thought Dr. Duan, the body would have to be a specimen.

Probably.

He decided, after pushing three different buttons in an elevator between the ground floor that led to the emergency room of the hospital and the basement that led to the lab that he shared, to wait in neither place, but in his office, justly suffering the physical pangs of a too-late evening the night before.

One of the more attractive nurses suggested that he should not smoke in the elevator, and he apologized, saying that he had not thought about it. For three floors they politely discussed smoking while he was trying not to stare at the delicate and lightly freckled breast cleavage appearing between the white lapels of her uniform. He wanted to be gallant, but he found himself turning his gaze forcibly, time and again, from her chest. He imagined her breasts bare. They were perfect. Breasts always were, in his imagination. He noticed the glimmering of opportunity, when somehow and not too smoothly she let him know she would be alone that evening.

He tried to decline the evening without declining the woman. It came out that he preferred a frozen corpse to her.

When he reached his tiny office, the phone was ringing. It was the emergency room. An American was there with a specimen. Did Dr. Duan want it brought to the laboratory?

"I don't know. No. Tell him to wait there. What does it look like?" he asked in Norwegian. He was fluent in four foreign languages: Norwegian, Swedish, German, and English. He preferred to work in two, however---Norwegian and English. Norwegian because he had worked here for the last four years and English because of American scientific journals.

"What does the specimen look like?" he asked again.

"I don't know, Dr. Duan. It's outside in a truck, and the man who brought it said you wanted it. He didn't say where."

"Tell him...tell him...."

"Yes?"

"Stay there. I'll be down to take a look at it," said Dr. Duan, deciding on the sure course. Not only was he nauseated from the previous night, but now the annoying little tension of trying to make sure he met someone at the right place in the sprawling university hospital complex made his stomach contract in little pains.

He ignored this and rapidly straightened up in front of a little mirror he whisked from a desk drawer. He was in his early forties, and his fleshy face hovered dangerously close to fat. His dark lips and slanted eyes created a sense of unhappiness that if not dispelled by a definite smile gave the impression he was constantly dissatisfied with his surroundings. But when he smiled it was a quantum leap into unheard of joy.

He dressed well, he knew----today, in British tweed jacket and gray flannel slacks, with a white Italian shirt and a severe British regimental tie. He did not believe in denying himself life's pleasures, and in no way did this detract from his commitment to his work.

He thought about this as he left his office on his way to the other side of the university complex. He had sought work as part of this exchange program just because of his commitment. Not that Peking would deny him any equipment or space. Indeed, the space was better back home. But back home, the Cold War was still being fought, this competition with the West.

It had led to dramatizing those scientific achievements which most captured the imagination----creating a two-headed dog through grafting techniques: parapsychology; and of course the freezing of the cat's brain for two months and returning it to certain functions, that is, getting it to transmit waves that could be recorded.

The important work here was not so much with the brain but with the blood, which at normal temperatures provided life and which at low temperatures became crystallized, causing massive cellular destruction. It wasn't that the brain had been revived, but that extensive work had been done with blood elements. Unfortunately, red blood cell counts and white blood cell counts, osmotic fragility, and hemolysis hardly trumped the triumph of socialism among the masses.

Therefore, significant work was subordinated to the imagination of some propagandists. It was natural, humanly natural, to drift into what would gain the most fame.

But Duan Qi wanted more. He wanted more for his country and for the people whose labors had paid for his education. He wanted more for all those scientists who had preceded him and on whose work he built. What Dr. Duan Qigang wanted was to add another solid brick to the body of knowledge for others to build on. He was not in competition with the West. He was partners with them, from the ancient Egyptians to the latest brain surgeons in New York City.

This made him no less a Chinaman, no less a believer in his form of government. It made him want to work outside of China and escape the competitive nature of Chinese science.

These things he thought about, going down in the elevator toward the main floor. He suddenly noticed the nurse with the cleavage had taken the elevator down with him and he had ignored her. He was also aware that his headache was gone and his stomach contractions had ceased.

He left the elevator stepping briskly. The big problem with cryonics, low-temperature medicine, was that too many people around the world had treated it like some kind of medical miracle, like resurrection.

Even today, especially in America, rich people with gargantuan bank accounts and fear of death were arranging for their dead bodies to be incarcerated in capsules, temperatures lowered rapidly with liquid nitrogen and sustained in that state by technology supported by the interest of those gargantuan bank accounts.

They froze the dead. And then expected some future scientists to resurrect the dead body. As Dr. Duan had told one person at one of those horrible embassy parties, "You don't need a scientist, you need a Christian minister. They believe in resurrection. I don't. It is possible as an article of faith, sir, not as a scientific fact."

The embassy had also prevailed upon him to speak at one of those cryonics societies that had sprung up around the world, many of those members entertained some fantasy of having a double life, one natural and the other through freezing.

"Yes, we might have a chance of suspending animation through cryonics. First, we need a volunteer. He, or she, has to have a good heart, be in perfect physical condition, and ideally be in the early to late twenties. Then we drain his blood, rapidly replacing it with a substance, probably glycerol, which also has a very good chance of killing him at normal temperatures, and we lower his temperature fast enough during this process---a very risky combination of blood transfer and temperature reduction. Do I have any volunteers?"

There was a hush in the hotel room, rented for that meeting.

"That may work if we had a volunteer," Dr. Duan went on. "Let me tell you what will not work: terminal cancer patients, already weak from the ravages of the disease; old people whose bodies have given out and have little chance of surviving now, let alone against the massive assault upon the body a freezing process entails; and, most of all, those people who have just died. If their bodies are not capable of sustaining life at 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit, how are they going to do so at below zero degrees Celsius?"

And then came that persistent rationale for the most unscientific of expectations. A hand had been raised and that old statement made. Dr. Duan kept reminding himself not to be cruel as he heard it.

"Sir, I am neither a scientist nor a doctor. But I do know this. If we bury someone and put them into the ground to decompose, there is zero chance of recovery. There is no chance. But if we freeze someone, on the chance that a later age will have cures for the disease, that person has a better than zero chance of recovery. Isn't that so?"

And Duan, holding back his rage, his voice lower than normal, each word precise, had answered:

"Yes, better than zero. You are right. It is as good as this lucky krone I have in my pocket, which I will sell you for everything you own. Put this krone in your mouth and you will never die. It is magic. Now, the odds are certain you will die. We have precedent for that assumption.

"So, you are certain of dying. But maybe the psychic believes that holding this krone in your mouth will give you eternal life, and keep you from dying. That, too, is a greater than zero possibility. And just as good. If you want resurrection, may I recommend some excellent Lutheran churches in this country."

The meeting had broken up. There had been a protest to the embassy that if Dr. Duan was any indication of the Sino-Scandinavian Friendship Pact, he was surely not doing the People's Republic of China any good, and that the writer had been previously well disposed toward communism before Dr. Duan's appearance at their meeting and now felt otherwise.

The true tragedy of the meeting came with a beautiful, pale blonde woman in her early twenties. There was an offer of seduction, and Duan had taken it. In the second week of the affair, Duan, glowing from every active corpuscle in his 42-year-old body, was asked to look at the girl's father. Perhaps Duan could do something with low-level temperatures to help the father. What diseases did the father have, Duan had asked; heart failure had been the answer.

"I would suggest a heart specialist."

"But they failed, Duan darling. That's what killed him."

The woman had wanted him to get her father dug up after eleven months of burial.

After that, Duan Qigang refused even to consider any prospect concerning his field that didn't come from a reputable scientist.

Early spring was coming to Norway, and Dr. Duan breathed gusts of moisture as he trotted through the courtyard between the building and the hospital. He tried to remember what the American scientist looked like, but all he could remember was Texas and that the man was someone tall.

At the emergency room, he saw someone who had to be Dr. Carson, but he didn't remember him that tall. The man was dressed like an Eskimo, a giant in fur.

"Dr. Carson?"

"Yes. Dr. Duan?"

"Yes. Where is this specimen you say you have for me? A whole body, yes?"

"Yes," said the American.

He stuffed a big glove in his parka. He explained he had been traveling since the day before and had just flown in and had kept the body wrapped in a tarpaulin. He was tired and sweating. And he was glad to be here.

Dr. Duan reached for a chit of paper that the American was taking from his shirt, but the American yanked it back and apologized. It was company business, and the body was outside.

"I understand," said Dr. Duan. "How did it die?"

"I don't know. I'm a geologist. We found it. Like the mastodon found in permafrost in the Soviet Union."

"It is a human body?" asked Dr. Duan. Suddenly he was experiencing severe doubts about what this man had brought him. A small rented van was parked, blocking access for ambulances.

"Yes, and it's in there."

"How badly decomposed is it?"

"I didn't look at it long. I didn't see any."

"Uhhum," said Dr. Duan, registering this fact and waiting for the rear door of the van to open. The big American swung the door open easily, and water broke out of the van. Dr. Duan saw a brownish tarpaulin. The hospital's lights glistened off the dark water at the bed of the truck, as if the water had broken out of the tarpaulin itself.

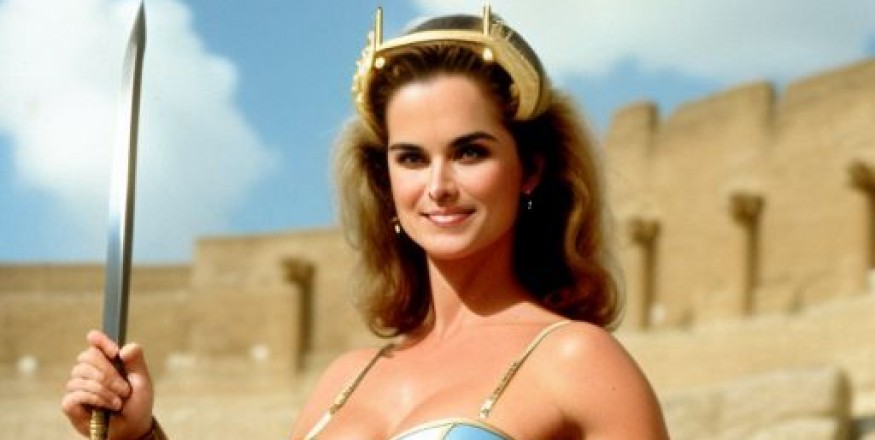

The big American reached inside and, with an effort to get the closed tarpaulin off, ripped a strand of cord with his massive hands. He pulled back an edge to the wall of the truck, and Dr. Duan saw long, dark hair through a smooth covering of ice.

The melting process had begun in the truck proper but had not reached the body. With grunts, the big American climbed into the back of the truck, and both he and Dr. Duan eased the tarpaulin away. The American had amazing strength, and Dr. Duan cautioned him not to drop the water-slick ice with the specimen inside.

A small light in the back of the van showed flashes of skin, with very little discoloration.

It was a muscular young woman. There was a wound, Dr. Duan found, in the right thigh, but that should not have been the cause of death.

"That was our fault," said the American. "Our core tube went right through it."

Dr. Duan pressed his forefinger into the cylindrical wound. He tried to feel the crack of crystals between thumb and forefinger. It was rubbery. He tried to find a vein, but there was not room enough to do this by eyesight alone since he was wedged against the side of the van, and the frozen specimen was right against him. If there was a vein at his fingers, it too had yet to be crystallized.

"My God!" gasped Dr. Duan, who did not believe in God. "She's beautiful. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you."

ns 15.158.61.51da2