x

x

Cha-Ka and his companions had no recollection of what they'd seen, after the Pylon had ceased to cast its hypnotic spell over their minds and to experiment with their bodies. The next day, as they went out to forage, they passed it with barely a second thought; it was not part of the ignored background of their lives. They could not eat it, and it could not eat them; therefore it was irrelevant.

Down at the river, the Others made their usual asinine threats. Their leader, a one-eared Paku of Cha-Ka's size and age, but in poorer health, even made a brief foray toward the tribe's territory, screaming loudly and waving his arms in an attempt to scare the opposition and to shore up his own courage.

The water out of the stream was nowhere more than 1 foot deep, but the farther One-Ear moved out into it, the more unsure and unhappy he became. Very soon he slowed to a halt, and then moved back, with exaggerated dignity, to join his companions. Otherwise, there was no change in the normal routine. The tribe gathered just enough nourishment to survive for another day, and nobody died.

That very night, the golden Pylon was still waiting; surrounded by its pulsing aura of light and sound. The program it had contrived, however, was now subtly different. Some of the Pakuni ignored it totally, as if it was concentrating on the most promising subjects.

Among those subjects was Cha-Ka; once more he felt inquisitive tendrils creeping down the unused byways of his brain. And presently, he started to see visions. They might have been within the golden Pylon, they might have been wholly inside his mind. In any case, to Cha-Ka they were completely real. Yet somehow the usual automatic impulse to drive off invaders of his territory had been lulled into quiescence.

His eyes beheld a peaceful family group, differing in only one respect from the scenes he knew. The male, the female, and two babies that had mysterious appeared before him were gorged and replete, with sleek and glossy pelts---and this was a condition of life that Cha-Ka had never thought possible. Unconsciously, he felt his own protruding ribs (note: the ribs of these creatures were hidden in dense rolls of fate). From time to time they stirred lazily, as they lolled at ease near a cave entrance, seemingly at peace with the world. Occasionally the big male emitted a monumental burp of contentment.

There was no other activity, and after five minutes the scene suddenly disappeared. The Pylon was no more than a glimmering outline in the darkness. Cha-Ka shook himself as if waking up from a dream, abruptly realized where he was, and led the tribe back to the caves.

He had no conscious memory of what he had seen; but that night, as he sat brooding at the entrance to his lair, his ears attuned to the noises of the world around him, Cha-Ka felt the first faint twinges of a new and potent emotion. It was a vague and diffuse sense of envy---of dissatisfaction with his life. Of its cause he lacked any idea, still less of its cure; but discontent had come into his soul-----and he had taken one little step toward humanity!

Night after night, the spectacle of those four plump Pakuni was repeated, until it'd become a source of fascinated exasperation, serving to increase Cha-Ka's eternal, gnawing hunger. The evidence of his eyes could not have produced this effect; it needed psychological reinforcement. There were gaps in Cha-Ka's life now that he would never remember, when the very molecules of his primeval brain were being twisted into new patterns. If he survived, those patterns would become eternal, for his genes would pass them on to future generations.

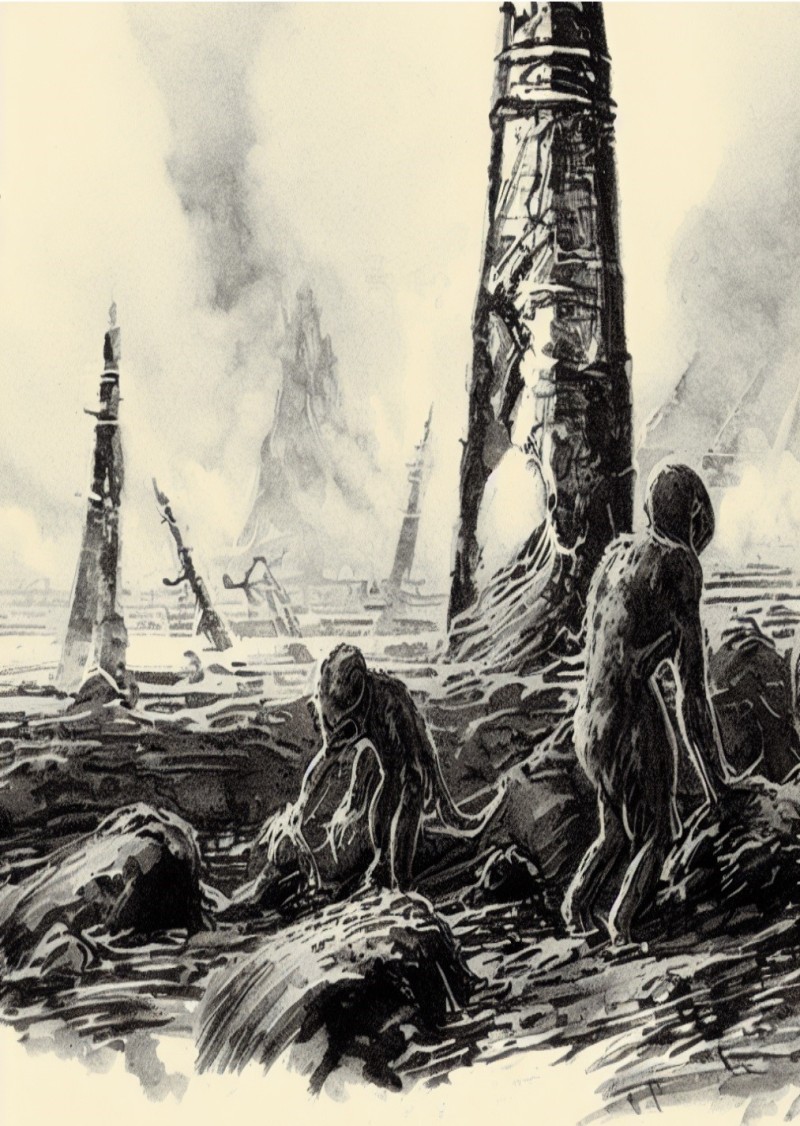

It was a slow, tedious business, but the golden Pylon was patient. Neither it, nor its replicas scattered across half the world, expected to succeed with all the scores of groups involved in the experiment. 100 failures wouldn't matter, not when one success could change the course of this planet's history.

By the time of the next new moon, the tribe had seen one birth and two deaths. One of these had been due to starvation; the other had happened during the nightly ritual, when a Paku had suddenly fainted while attempting to tap two pieces of stone delicately together. At once, the Pylon had darkened, and the tribe had been released from the spell. But the fallen Paku had not moved; and by the morning, of course, the body was gone.

There had been no performance the next night; the Pylon was still analyzing its mistake. The tribe streamed past it through the gathering dusk, ignoring its presence absolutely. The night after, it was ready for them again. The four plump Pakuni were still there, and now they were doing extraordinary things. Cha-Ka began to tremble uncontrollably; he felt as if his brain would explode, and wanted to avert his eyes. But that remorseless mental control would not relax its grip; he was compelled to follow the less to the end, although his instincts rebelled against it.

Those instincts had served his ancestors well, in the days of warm rains and lush fertility, when food was to be had everywhere for the plucking. Now times had changed, and the inherited wisdom of the past had become folly. The Pakuni must adapt, or they will die---like the mighty lizards who had come before them, and whose bones now lay sealed within the limestone hills.

So Cha-Ka stared at the golden Pylon with unblinking eyes, while his brain lay open to its still unsure manipulations. Often he felt nausea, but always he felt hunger; and from time to time his hands clenched unconsciously in the patterns that would determine his new way of life.

As the line of warthogs moved snuffling and grunting across the trail, Cha-Ka came to an abrupt halt. Pigs and Pakuni had always ignored each other, for there was no conflict of interest between them. Like most animals that didn't compete for the same food, they just stayed out of one another's way.

Yet now Cha-Ka stood looking at them, wavering to and fro uncertainly as he was buffeted by impulses which he could not understand. Then, as if in a dream, he started searching the ground---though for what, he could not have explained even if he had had the power of speech. He would recognize it when he saw it.

It was a heavy, pointed stone that was six inches in length, and though it did not fit his hand perfectly, it would do. As he swung his hand around, puzzled by its suddenly increased weight, he felt a pleasing sense of power and authority. He started to move toward the nearest pig.

It was a young, foolish beast, even by the undemanding standards of warthog intelligence. Though it observed him out of the corner of its eye, it didn't take him seriously until way it was too late. Why would it suspect these innocent creatures of any evil intent? It went on rooting up the grass until Cha-Ka's stone hammer obliterated its dim consciousness. The remainder of the herd went on grazing unalarmed, for the murder had been swift and silent.

All the other Pakuni had stopped to watch, and now they crowded round Cha-Ka and his victim with admiring wonder. Presently one of them picked up the bloodstained weapon, and began pounding on the dead pig. Others joined in with any sticks and stones that they could gather, until their target began a gruesome disintegration.

Then they became bored; some wandered away, while others stood hesitantly around the barely-recognizable corpse----the future of a planet hinging upon their decision. It was a surprisingly long time before one of the nursing females began to lick the gory stone she was holding in her paws.

And it was longer still before Cha-Ka, even after all that he'd been shown, really understood that he need never be hungry again.

440Please respect copyright.PENANAhHZtb135c3