x

x

As I walked into the security command center of SchwarzTech Towers, I felt like I had stepped onto the set of a "Star Wars" movie. The room was vast, with walls lined by enormous, curved screens displaying a multitude of live security feeds, complex schematics, and real-time data analysis. The lighting was dim, with a soft blue glow emanating from the floor and ceiling, creating an almost ethereal atmosphere.

In the center of the room, a holographic table projected a three-dimensional, rotating image of the entire building, complete with moving indicators of personnel and security threats. The operators, seated in sleek, ergonomic chairs, were equipped with augmented reality headsets that allowed them to interact with the holographic displays through simple gestures. Their movements were precise and fluid, like a choreographed dance with the cutting-edge technology they commanded.

Everywhere I looked, there were advanced touchscreens and voice-activated controls. The air was filled with a faint hum of servers and the occasional beep of alerts being acknowledged. Even the chairs and consoles seemed to adjust automatically to the operator's needs, responding to body movements and commands as if they were an extension of the users themselves.

I couldn't help but compare this ultra-tech marvel to the security setups back home. In the U.S., our systems were bulky, often outdated, and riddled with inefficiencies. We were stuck using clunky keyboards and grainy monitors, constantly battling software glitches and hardware failures. Here, everything seemed to flow seamlessly, a testament to the Germans' relentless pursuit of perfection and innovation.

A wave of disgust washed over me. It wasn't just envy; it was frustration with the stark reality that we were falling so far behind. This command center was a tangible reminder of our bureaucratic bloat and overregulation, the very things that stifled American progress and innovation. We were stuck in the past, while the Germans were living in the future.

As I stood there, trying to mask my disdain, one of the operators glanced up at me. His expression was neutral, almost indifferent, as if he knew exactly what I was thinking. I could sense a smirk behind his professionalism, a silent acknowledgment of the technological chasm that separated our nations.

I forced a nod, clenching my jaw to keep my frustration in check. "Yeah, impressive," I muttered, unable to shake the feeling of inferiority that the sight of this high-tech haven had stirred within me. This wasn't just a room full of advanced gadgets; it was a symbol of everything we were missing, everything we had lost sight of in our struggle to keep up. And standing there, in the heart of SchwarzTech's futuristic command center, I couldn't help but wonder if we'd ever be able to bridge that gap.

Tom Smolley was the guard on duty. He was a black man in his mid forties. His gray SchwarzTech Security uniform was soaked around the collar, and dark under the armpits.

He asked us to leave t he door open as we entered. He appeared noticeably uneasy to have us there. I sensed he was hiding something, but Rehn approached him in a friendly way. We showed our badges and shook hands. Rehn managed to convey the idea that we were all security professionals, having a little chat together.

”Must be a busy night for you, Mr. Smolley.”

”Yeah, sure. The party and everything.”

“At least you’ve got this high-tech marvel all to yourself.”

Smolley wiped sweat from his forehead. “Far from it. All of them packed in here. Jesus.”

I said, “All of who?”

Rehn looked at me and s aid, “After the Germans left the 46th floor, they came down here and watched us on the monitors. Isn’t that right, Mr. Smolley?”

Smolley nodded. “Not all of ‘em, but quite a few. Down here, smoking their damn cigarettes, staring and puffing and passing around faxes.”

”Faxes?”

”Oh, yeah, every few minutes, somebody’d bring in another fax. You know, in German. They’d pass it around, make comments. Then one of ‘em would leave to send a fax back. And the rest would stay to watch you guys up on the floor.”

Rehn said, “And listen, too?”

Smolley shook his head. “No. We don’t have audio feeds.”

”I’m shocked,” Rehn said. “This equipment seems so futuristic.”

”Futuristic? Hell, it’s a hundred years ahead of its time. These folks, I tell you one thing. They do it right. They’ve got the best fire alarm and fire prevention system. The best earthquake system. And of course the best electronic security system: best cameras, detectors, holographic projectors, everything.”

“I can see that,” Rehn said. “That’s why I was shocked that they didn’t have audio.”

”No. No audio. They do high-resolution video only. Don’t ask me why. Something to do with the cameras and how they’re installed, is all I know.”

On the curved screens I saw five different views of the 46th floor, as seen from different cameras. Apparently the Germans had installed cameras all over the floor. I remembered how Rehn had walked around the atrium, staring up at the ceiling. He must have spotted the cameras then.

Now I watched Ramirez in the conference room, directing the teams. She was smoking a cigarette, which was completely against regulations at a crime scene. I saw Kelli stretch and yawn. Meanwhile, McClung was getting ready to move the girl’s body off the table onto a gurney, before zipping it into the bag.

Then it hit me! They had cameras up there, five different cameras covering every part of the floor.

I said, “Oh my God” and I spun around, very excited. I was about to say something when Rehn smiled at me in an easy way, and placed his hand on my shoulder. He squeezed my shoulder hard.

“Lieutenant,” he said.

The pain was incredible. I tried not to wince.

“Yes, Captain?”

”Would you mind if I asked Mr. Smolley one or two questions.”

”No, Captain. Go right ahead.”

”Perhaps you’d take notes.”

”Good idea, Captain.”

He released my shoulder. I got out my notepad

Rehn sat on the edge of the table and said, “Have you been with SchwarzTech long, Mr. Swolley?”

”Yes, sir. Six years now. I started over in their La Habra plant, and when I hurt my leg in a car accident and couldn’t walk too good, they moved me to security in the plant. Because I wouldn’t have to walk around, you see. Then, when they opened the Torrance plant, they moved me over there. My wife got a Job in the Torrance plant, too. They do Volkswagen subassemblies. Then, when this building opened, they brought me here, to work nights.” .

”Yes, it comes to about 6 year just like you said. You must like it.”

”Well, I tell you, it’s a secure job. That’s something in America. I know they don’t think much of black folks, but they always treated me okay. And hell, before this I worked for GM in Van Nuys, and that’s——you know, that’s gone.”

”Yes,” Rehn said sorrowfully.

”That place,” Swolley said, shaking his head at the memory. “Jesus. Those management assholes they used to send down to the floor. You couldn’t believe it. MB fuckin’ A, out of Detroit, little weenies didn’t know jack shit. They didn’t know how the line worked. They didn’t know a tool from a die. But they’d still order the foremen around. They’ll all pulling in two hundred fuckin’ thousand a year and they didn’t know shit. And nothing ever worked right. The cars were all pieces of shit. But here,” he said, tapping the counter. “Here, I got a problem, or something doesn’t work, I tell somebody. And they come right down, and they know the system, how it works, and we go over the problem together, and it gets fixed PDQ. Problems get fixed here. That’s the difference, I tell you; these guys pay attention.”

”So you really do like it here.”

”They always treated me okay,” Swolley said, nodding.

That didn’t exactly strike me as a glowing endorsement. I had the feeling this guy wasn’t committed to his employers and a few questions could drive the wedge. lol we had to do was encourage the break.

”Loyalty is important,” Rehn said, nodding sympathetically.

“It is to them,” he said. “They expect you to show all this enthusiasm for the company. So you know, I always come in fifteen or twenty minutes early, and stay fifteen or twenty minutes after the shift is over. They like you to put in the extra time. I did the same at Van Nuys, but nobody ever noticed.”

”When is your shift?”

”I work nine to seven.”

”And tonight? What time did you come on duty?”

”Quarter to nine. Like I said, I come in fifteen minutes early.”

The original call had been recorded about 8:30. So if this man came at a quarter to nine, he would have arrived almost fifteen minutes too late to see the murder.

“Who was on duty before you?”

”Well, it’s usually Ed Bishop. But I don’t know if he worked tonight.”

”Why is that?”

The guard wiped his forehead with his sleeve, and looked away.

“Why is that, Mr. Swolley?” I said, with a little more force.

The guard blinked and frowned, saying nothing.

Rehn said quietly, “Because Ed Bishop wasn’t here when Mr. Swolley arrived tonight, was he, Mr. Swolley?”

The guard shook his head. “No, he wasn’t.”

I started to ask another question, but Rehn raised his hand. “I imagine, Mr. Swolley, you must have been pretty surprised when you came into this room at a quarter to nine.”

”You’re damn right I was,” Swolley said.

”What’d you do when you saw the situation?”

”Well, right away, I said to the guy, ‘Can I help you? Very polite but still firm. I mean, this is the security room. And I don’t know who this guy is. I’ve never seen him before. And the guy is tense, very tense. He says to me, ‘Get out of my way.’ Real pushy, like he owns the world. And he shoves past me, taking his briefcase with him. I say, ‘Excuse me, sir, I’ll have to see some identification.’ He doesn’t answer me, he just keeps going. Out the lobby and down the stairs.”

”Didn’t you try to stop him?”

”No, sir, I didn’t.”

”Because he was German?”

”You got that right. But I called up to central security up on the 9th floor to say I found a man in the room. And they say, ‘Don’t worry, everything’s fine.’ But I can hear they’re tense too. Everybody’s tense. And then I see on the monitor….the dead girl. So that’s the first I knew what it was about.”

Rehn said, “The man you saw, can you describe him?”

The guard shrugged. “Thirty, thirty-five. Medium height. Dark blue suit like they all wear. Actually, he was more hip than most of them. He had this tie with triangles on it. Oh—-and a scar on his hand, like a burn or something.”

”Left or right hand?”

”Left. I noticed it when he was closing the briefcase.”

”Could you see inside the briefcase?”

”No.”

”But he was closing it when you came in the room.”

”He was.”

”Was it your impression that he took something from this room?”

”I really couldn’t say, sir.”

Swolley’s evasiveness began to annoy me. I said, “What do you think he took?”

Rehn shot me a look.

The guard went bland: “I really don’t know, sir.”

Rehn said, “Of course you don’t. There’s no way you could know what was in somebody else’s briefcase. By the way, do you make recordings from the security cameras here?”

”Yes, we do.”

”Could you show me how you do that?”

”Sure thing.” The guard escorted us to a section of the room that housed their state-of-the-art video recording system. The setup was unlike anything I had ever seen. At the heart of the system was a series of transparent, cylindrical towers filled with a faintly glowing, blue liquid. The liquid pulsed rhythmically, reminiscent of a living, breathing organism, as it processed and stored vast amounts of data in real-time.

"That’s the Quantum Data Repository," Swolley explained, a hint of pride in his voice. "They utilize quantum computing principles to record and store video footage at a level far beyond conventional systems."

I watched in awe as he demonstrated the system. A holographic interface projected from the surface of one of the cylinders, displaying a three-dimensional timeline of recorded events. The guard manipulated the timeline with a wave of his hand, zooming in and out with fluid motions that made it seem like he was conducting an orchestra.

"With this system, we can capture video from thousands of angles simultaneously," he continued. "Each camera feeds into the quantum processors, allowing us to create a fully interactive, 360-degree reconstruction of any event. You can view the scene from any perspective, even ones that weren't originally captured by the cameras."

He tapped on the holographic timeline, and a scene materialized in the air before us—a perfect, three-dimensional replay of the lobby of SchwarzTech Towers. We could see every detail, every person, from every possible angle. The guard moved through the timeline, showing how they could isolate specific individuals, enhance audio, and even analyze micro-expressions on faces with incredible accuracy.

"This system also uses predictive algorithms to fill in gaps," the guard added. "If there's a blind spot, the AI can extrapolate based on surrounding data, ensuring we miss nothing."

I couldn't help but feel a pang of jealousy and frustration. America's video recording systems were clunky and limited. We relied on fixed camera angles, grainy footage, and time-consuming manual reviews. These guys had a system that not only recorded events in stunning clarity but also allowed for comprehensive, interactive analysis.

Rehn, still trying to process the sheer sophistication of the system before him, furrowed his brow and turned Swolley. "This is all pretty mind-blowing," he said, his voice tinged with a mix of admiration and skepticism. "But I have to ask—where exactly are these recordings stored? I mean, with a system this advanced, it must require some serious infrastructure. Is it all kept on-site, or do you have some off-site, ultra-secure storage facility for all this data?

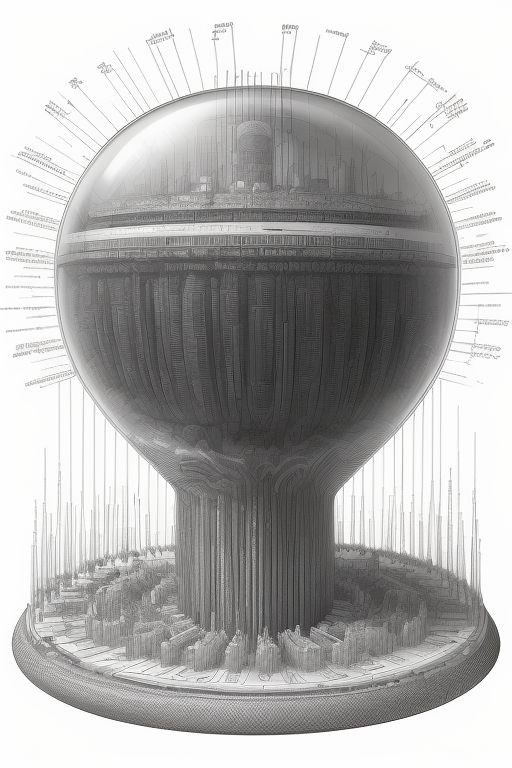

Swolley led us to another section of the room, where a massive, translucent sphere hovered above the ground, suspended by magnetic fields. Inside the sphere, intricate patterns of light pulsed and shifted, resembling a miniature galaxy in constant motion.

"This," Swolley began, "is our Neural Quantum Storage Matrix. It's not just any storage system; it utilizes neural network principles combined with quantum computing to ensure real-time data integrity and almost infinite storage capacity. The recordings are fragmented and encrypted at the quantum level, then distributed across multiple secure nodes globally. This ensures that even if one part is compromised, the data remains intact and accessible."

He tapped a control panel, and the sphere projected a holographic map of the building, highlighting the various secure nodes scattered across different sections. Each node is housed in a fortified facility with top-tier security measures. The redundancy and encryption make it virtually impossible for unauthorized access."

Swolley looked at us with a satisfied expression. "Not bad, huh? But it wasn't easy getting up to speed with all this tech. It's not bad enough I had to study Popular Mechanics articles to make sense of how it worked, but I also had to learn German, as if Spanish wasn’t bad enough." They really don't make it easy, but once you get the hang of it, it's a game-changer. They’re light-years ahead of what we’re used to.”

Rehn hesitated. “Perhaps I’d better write this down.” He produced a small pad and a pen. “Now, how long does each recording last and how many different sets do you have?”

”Eight hours. And we have nine different sets.”

Rehn wrote for a moment, then shook his pen irritably. “Damn thing! It’s out of ink. You got a wastebasket?”

Swolley pointed to the corner.

“Over there.”

”Thank you.”

Rhen threw the pen away. I gave him mine. He resumed his notes.

“You said there are nine sets, Mr. Swolley?”

”Right. Each set is numbered with letters, from A to I. Now when I come in at 9:00, I eject the nodes and see whatever letter is already in there, and put in the next one. Like tonight, I took out Node C, so I put in Node D, which is what’s recording now.”

”I see,” Rhen said. “And where did you put node set C?”

”Right here.” Swolley walked over to a sleek control console adjacent to the floating sphere of the Neural Quantum Storage Matrix. His fingers danced over the holographic interface.

A section of the sphere's surface shimmered and then projected a series of concentric rings, each one labeled with different data categories and time stamps. "The retrieval process is incredibly efficient. Think of these rings as a dynamic drawer system," Swolley explained. "Each ring represents a different category of data, and within each category are layers of encrypted recordings."

Swolley tapped a specific ring, and it expanded outward, displaying a timeline with multiple sub-categories and events. "To access a specific recording, we simply navigate through these layers. The system uses an AI-driven interface to predict and highlight the most relevant segments based on our search parameters."

He gestured towards a small, rectangular panel embedded in the console. "This is where the drawer analogy comes in. This panel functions like a physical drawer, but instead of pulling it open, we use biometric verification." Swolley placed his hand on the panel, and it scanned his fingerprints and retina simultaneously. The panel slid open with a soft hum, revealing a compartment containing a slim, crystalline data rod.

"The data rod is like a physical key," Swolley continued. "Once authenticated, it allows us to download and access specific segments of data from the quantum storage. The rod itself is encoded with unique access permissions, ensuring that only authorized personnel can retrieve sensitive information."

Swolley inserted the data rod into a slot on the console. Instantly, the holographic interface projected a detailed, three-dimensional reconstruction of a recent event captured by the system. "From here, we can interact with the recording in real-time, analyze different perspectives, and even enhance audio and visual elements."

“I think I understand now,” Rehn said. “What you actually do is use nine sets in rotation.”

”Exactly. That way each set gets used once every three days.”

”Right. And how long has the security office been using this system?”

”The building’s new, but we’ve been going, oh, maybe two months now.”

“I must say it’s way above my pay-grade,” Rehn said appreciatively. “Thank you for explaining this to us. I have only a couple of other questions.”

”Sure.”

“First of all, these counters here…” Rehn said, pointing to the transparent orb suspended in mid-air by advanced holographic technology. The timer/clock was a marvel of German design, with its intricate layers of glowing rings and numbers. “They seem to show the elapsed times since the nodes began recording. Is that right? Because it’s now almost 11:00 and you put the tapes in at nine, and the top recorder says 1:55:30 and the next recorder says 1:55:10, and so on.”

”Yes, that’s right. I put the nodes in one right after the other. It takes a few seconds between nodes.”

”I see. These all s how almost two hours. But I notice that one ring of numbers at the bottom shows an elapsed time of only thirty minutes. Does that indicate a malfunction of some kind?”

”What?” Swolley said, frowning. “I guess it does. ‘Cause I changed the nodes one after another, like I said. But these recorders are technologically way ahead of their time. Sometimes there are glitches. Or we had some power problems. Could be that.”

”Yes, quite possibly,” Rehn said.

”Can you tell me which of these—-nodes is hooked to this recorder?”

”I sure can.” Swolley read the number off the clock, and went out to the main room with the monitor screens.

”It’s camera 46/6,” he said. “This view here.” He tapped the screen.

It was an atrium camera, and it showed an overall view of the 46th floor.

”But you see,” Swolley said, “the beauty of the system is, even if one recorder screws up, there are still other cameras on that floor, and the video recorders on the others seem to be working okay.”

”Yes, they do,” Rehn said. “By the way, can you tell me why there are so many cameras on the 46th floor?”

”You didn’t hear it from me,” Swolley said. “But you know how they like efficiency. The word is, they are going to kontinuierliche verbesserung the office.”

”So basically these cameras have been installed to observe workers during the day, and help them improve their efficiency?”

”So I heard.”

”Well, I think that’s it,” Rehn said. “Oh, one more question. Do you have an address for Ed Bishop?”

Swolley shook his head. “Nope.”

”Have you ever been out with him, socialized with him?”

”Yeah, but not much. He’s a weird guy.”

”Ever been to his apartment?”

”Nope. He’s kinda secretive. I think he lives with his mother or something. We usually go to this bar, El Capitan, over by the airport. It’s his favorite hangout.”

Rehn nodded. “Oh, one final question: where is the nearest pay phone?”

”Out in the lobby, and around to your right, by the restrooms. But you’re welcome to use the phone here.”

Rehn shook the guard’s hand warmly. “Mr. Swolley, I appreciate your taking the time to talk to us.”

”No problem.”

I gave the guard my card. “If you think off anything later that could help us, Mr. Swolley, don’t hesitate to give me a call.”

And I left.

Rehn stood at the pay phone in the lobby. It was one of those new standing booths that has two receivers, one on either side, allowing two people to talk on the same line at once. These booths had been installed in Berlin years ago, and were now starting to show up all over Los Angeles. Of course, Pacific Bell was no longer the sole provider of American public pay phones. German manufacturers had penetrated that market, too. I watched Rehn write down the phone number in his notebook.

“What’re you doing?”

“We have two separate questions to answer tonight. One is how the girl came to be killed on an office floor. But we also need to find out who placed the original call, notifying us of the murder.”

”And you think the call might’ve been placed from this phone?”

”Possibly.” He closed his notebook and glanced at his watch. “It’s late. We better get a move on.”

”I think we’re making a big mistake here.”

”Why’s that?” Rehn asked.

”I don’t know if we should leave the nodes or whatever those things are in that security room. What if someone switches them while we’re gone?”

”They’ve already been switched,” Rehn said.

”How do you know?”

”I gave up a perfectly good pen to find out,” he said.

”Oh, come on.” He started walking toward the stairs leading down to the garage. I followed him.

”You see,” Rhen said, “when Swolley first explained that system of rotation, it was immediately clear to me that there might’ve been a switch. The question was how to prove it.”

His voice echoed in the concrete stairwell. Rehn continued down, taking the steps two at a time. I hurried to keep up.

Rehn said, “If somebody switched the nodes, how would they go about it? They’d be working hastily, under pressure. They’d be scared of making a mistake. They certainly wouldn’t want to leave any incriminating recordings behind. So they’d probably switch an entire set and replace it. But replace it with what? They can’t just put in the next set. Since there are only nine sets of nodes, altogether, it’d be too easy for someone to notice t hat one set was missing and the total was now eight. There’d been an obvious empty drawer. No, they’d have to replace the set they were taking away with a whole new set. Twenty brand-new nodes. And that meant I should check the trash.”

”That’s why you tossed your pen away?”

”Yes. I didn’t want Swolley to know what I was doing.”

”And?”

"I saw the wrappers from the new nodes earlier. "The trash was full of them.”

”I see.”

"The wrappers are made of this shiny, reflective material—almost like Mylar, but thicker. And they have these intricate blue and silver patterns on them, kind of like a futuristic circuit board design. They stood out because I've seen something similar before, back when I toured a high-security data center in Silicon Valley. Rehn shook his head, a smirk forming on his lips. "I recognized them because the patterns are unique to quantum storage units. Only a handful of companies use that specific design to protect their equipment during shipping. It looks like SchwarzTech just installed some brand-new, cutting-edge nodes. No wonder their system is light-years ahead of anything we've got in this country.”

”I see.” Somebody had come into the security room, taken out twenty fresh nodes, unwrapped them, written new labels, and popped them into the video machines, replacing the original nodes that recorded the murder,” I said, “If you ask me, Swolley knows more than he was telling us.”

”Maybe,” Rehn said, “but we’ve got important things to do. Anyway, there’s a limit to what he knows. The murder was phoned in about eight-thirty. Swolley arrived at a quarater to nine. So he never saw the murder. We can assume the previous guard, Bishop, did. But by a quarter of nine, Bishop was gone, and an unknown German man was in the security room, closing up a briefcase.”

”You think he’s the one who switched the nodes?”

Rehn nodded. “Very possibly. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if this man was the killer himself. I hope to find that out at Miss Kensington’s apartment.” He threw open the door and we went into the garage.

A line of party guests waited for valets to bring their cars. I saw Baumann chatting up Mayor Tomlinson and his wife. Rehn steered me toward them.

Standing alongside the mayor, Baumann was so cordial he was almost obsequious. He gave us a big smile.

“Ah, gentlemen. Is your investigations proceeding satisfactorily? Is there anything more I can do to help?”

I didn’t get really angry until that moment: until I saw the way he toadied up in front of the mayor. It made me so mad I began to turn red. But Rehn took it in stride.

“Thank you, Herr Baumann,” he said with a slight bow.

”The investigation is going well.”

”You’re getting all the help you asked for?” Baumann said.

”Oh, yes,” Rehn said. “Everyone has been very cooperative.”

”Good, good. I’m glad.” Baumann glanced at the mayor, and smiled at him, too. He was all smiles, it seemed.

”But,” Rehn said, “there’s just one thing.”

”Just name it. If there’s anything we can do….”

”The security nodes have been removed.”

”Security nodes?” Baumann frowned, clearly caught off-guard.

”Yes,” Rehn said. “Recordings from the security cameras.”

“I know nothing at all about that,” Baumann said. “But let me assure you, if any nodes exist, we will provide you with the means to examine them.”

”Thank you,” Rehn said. “Unfortunately, it seems the crucial nodes have been removed from the SchwarzTech security office.”

”Removed? Gentlemen, I believe there must be some mistake.”

The mayor was watching this exchange closely.

Rehn said, “Maybe, but I don’t think so. It’d be reassuring, Mr. Baumann, if you were to look into this matter yourself.”

”But of course,” Baumann said. “But I must say again. I can’t imagine, Captain Rehn, that any of our nodes are missing.”

”Thank you for checking, Mr. Baumann,” Rehn said.

”Not at all, Captain,” he said, still smiling. “It is my pleasure to assist you in any way I can.”