x

x

"We could make a stretcher," Mr. Del Carlo said, already on his feet and hobbling out of the room. "I was a builder, you know. Got all kinds of things laying around from past jobs."

Richard had suggested using a wheelbarrow to carry his mother, but the thought of her falling out into the dirt and broken glass along the way made him discard that idea even as he voiced it. Did the Del Carlos even have a patio lounge? Maybe they could roll it downhill to the hospital. But even that idea wouldn't work. She'd be jostled and bumped. She'd be a mass of ooze and pain by the time they got her a block away.

"A stretcher. Good idea."

It was Washington's voice behind him, weak yet firm. He'd stopped vomiting during the night and Mrs. Del Carlo's care---aspirin and forced liquid---had brought down his fever.

"How do you feel, Washington?" Richard asked.

"Like a wet dishrag." Washington forced a weak smile. "Don't worry. I don't think it's radiation. Probably that nervous stomach of mine, or I'd still be puking." He gave an embarrassed laugh.

"He shouldn't be out of bed," Mrs. Del Carlo said. "He's dehydrated. That fever won't stay down."

Mr. Del Carlo sighed. "Ada, Ada. Why don't you see what the children need to take with them?" He turned to Richard. "Boys, give me a hand here, will you? These poles will do fine."

Richard helped pull 2 eight-foot-long poles form under a pile of lumber stacked on a shelf. "Put them on that workbench. Now where's that old tarp?" Mr. Del Carlo beamed the flashlight along the various shelves of building materials until he found what he wanted. "There. Take that down. It's heavy----there's likely twenty, maybe 30 feet of the stuff---but that will be just the ticket."

Richard couldn't quite visualize how the boards, rods and tarp would all go together to make a stretcher, but he kept silent, unwilling to show his ignorance. He saw the light of comprehension already dawning in his brother's eyes as they unrolled the unwieldy canvas. "Oh, I get it," Washington said. "You'll cut the tarp so you have the gromets on one side and tie to one of the rods. But what about the other side? How will you secure that? Got a stapling gun?"

"Wish I did."

"Then how? Oh! You're gonna roll the tarp over the rod then nail those boards together with the tarp between." Washington's hand trembled, and perspiration dropped down one cheek.

"Something like that," Mr. Del Carlo said.

Something like that, Richard thought. It was so obvious, but he hadn't been able to see it.

The cutting of the tarp took the longest time, but once done, Richard and Washington went at tying twine through the grommets while Mr. Del Carlo hammered the wood holding the tarp on the opposite side. Suddenly the emergency broadcast system began sending again. They all looked up.

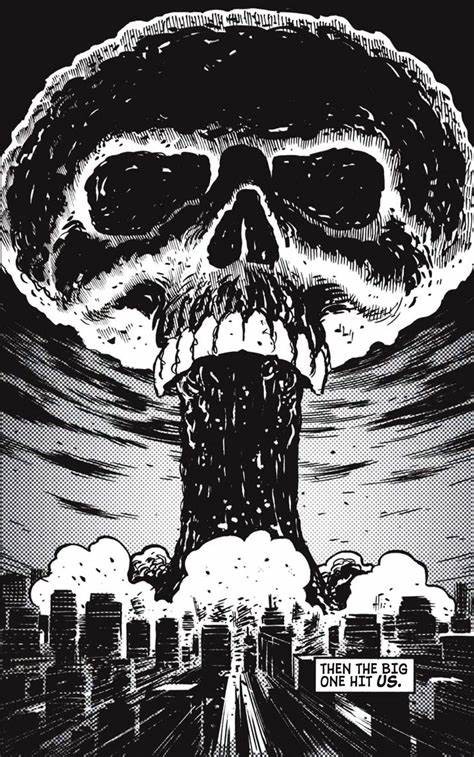

"This is the Emergency Broadcast System," the voice said. "All persons in coastal areas from Santa Barbara south to La Jolla are advised to shelter in place until further notice. Foothill residents may leave their homes, as the nuclear cloud is moving westward. Please assist your neighbors. State and federal assistance is being mobilized, but it may be forty-eight hours or more before it reaches your community. Damage is extensive. Roads and airfields are blocked or damaged. Until help comes, you must make every effort to extinguish your own fires and remove trees or other obstacles from roadways. Stay tuned for further information and instructions."

"Boy, were we lucky," Washington said softly. "The winds must be carrying that nuclear cloud to sea. Thing bothering me is, what happens when the Santa Anas die down?"

Mr. Del Carlo put down his hammer. "Just take it a minute at a time, son. That's all any of us can do. For now---we've made a decent enough stretcher. Let's see how we can move your dear mother without hurting her too much. Then you can be on your way."

Finally they stood together at the Del Carlos' front door, ready to leave. Mrs. Del Carlo hugged each of them as if she thought she'd never see them again, tears in her eyes. "If you can, let us know how it goes," Mr. Del Carlo said to Richard. "Take good care of yourselves." He put an arm around his wife and stepped aside.

Richard took the lead, a stretcher pole in each hand. Behind him his mother lay, covered by a clean white sheet on the canvas. Stacey and Washington each held one of the back poles. But within a block Washington began faltering.

"Stacey," Richard called. "Give Washington a rest. Can you take the full load?"

"I'll give it my all." She grasped both rods, but the weight was more than expected, and she almost fell.

"Washington, come up here and hang onto me," Richard said. He spoke irritably. His own arms ached from the weight, and he couldn't see how Stacey would hold out all the way. He scanned the debris-filled streets for help, but the people outdoors seemed busy with their own.

"It's easy, Stacey," he said, trying to sound lighthearted. "Larkin makes us go beyond what we think we can do all the time. When I'm running, and I think I can't go another step, I tell myself----just ten more, then just nine more, then just eight more."

Stacey stumbled, nearly dropping her end of the stretcher. Richard called out to her sharply. "I can't do it!" she protested, tears in her eyes. "My arms are shaking...."

"Come on," he urged. "Just tune it out. I'll talk to you. You know Mr. Del Carlo? Well Mom says he's eighty! Spry as a puppy, too. Last week he was up on our roof putting a screen in the chimney." As he maneuvered around a downed telephone pole, he took in the scene ahead. So many fallen trees, so many smoldering homes. So many people standing around in shock, or hysterical. So many burned and miserable people carrying belongings out of their homes, wandering aimlessly.

Richard gazed skyward as he heard what sounded like a squadron of helicopters overhead, but he still couldn't see anything.

Washington leaned heavily on him, his face unnaturally pale, and his mom whimpered from time to time as they moved too roughly. He welcomed the sound, though each time it hurt like a blow to the stomach. It meant she was still alive. Everything depended on him now. He had to keep Washington going, Stacey too.

"Hey, you should hear the funny story Mr. Del Carlo told Mom," Richard said, hoping to get Stacey's mind off her pain. "There's this couple, married 75 years, goes to a judge to ask for a divorce. 'She's impossible,' he said, and he gives all the reasons why he hates her. And she says, 'He's impossible,' and goes on non-stop about him. 'If you hated each other so much all these years, why did you wait so long to get a divorce?' the judge asks. 'We stayed together for the sake of the kids, and now they're all dead,' the couple says."

When Stacey didn't even smile, he said, "You know---maybe in a way, John Hinckley Jr. did us a favor...." He paused. "Stacey, you're supposed to ask me what did he do."

"All right.... what did he do?" Stacey replied weakly.

Good, she's listening, he thought. He tried to readjust his hold on the stretcher without jarring his mother. "Thanks to him, we won't need lights at night. People will glow in the dark!"

He heard a weak titter from Stacey and glanced back. She was very near exhaustion, and they were still blocks from the hospital. He halted near a home relatively undamaged by the blast or fire, set the stretcher carefully on the ground, and unhooked a canteen of water from his jeans. "Drink, Washington," he urged, "and here's more aspirin." He shook three pills into his brother's trembling hand and held the canteen to his lips. Glassy-eyed, Washington watched him uninterested.

"Turkey," Richard chided as he touched his brother's hot forehead. A chill of fear raced through him. He spilled some of the precious water into his hand and patted it on his brother's face. "You're just trying to get out of the heavy work, that's all." Washington didn't answer, and Richard's heart contracted. Normally Washington would never let him get away with a taunt like that. As much as he used to hate the put-downs, he'd give anything for one now, no matter how harsh.

"Okay, let's get going," he said gruffly. "Stacey? Lift!" He sifted through his repertoire of jokes and funny tales and began telling another, but Stacey wasn't listening.

Washington's weight on him, plus the weight of his mother, made his arms feel like they were being ripped from their sockets. He fixed his eyes on the ground and trudged along, gritting his teeth.

"I can't.... I can't do this anymore," Stacey cried in anguish as they came in sight of the Fellowship of Jesus Christ Gospel Church.

"Just a little farther. Just ten more steps...."'

Stacey shook her head and slowly dropped to her knees, lowering her end to the ground. She began to cry quietly. "I can't even lift my arms. Look."

"Stay here. I'll see if I can get help from the church." He crouched beside his mother. ""You okay, Mom?" She barely nodded; her eyes were shut. "I'll get you there, don't worry." Hs throat knotted. Then he sprinted around the overturned cars to the church across the street.

The church lawn was a sea of people, all lying still, all silent, all seemingly lifeless. Some of the people on the church lawn were in a state of shock, overwhelmed by the chaos and tragedy surrounding them. They were unable to process what had happened and were stuck in a state of numbness, unable to move or react. He hated to look at them, really hated it. Some were burned, others cut, bleeding, limbs either broken or torn off. The smell of smoke, now mixed with that of vomit, body odor, and worse, made his stomach churn. He tugged at a woman rushing by, carrying a heavy bucket in one hand and an armload of towels in another. "Excuse me, can anyone help me? My mother is across the street on a stretcher. I need someone to help me carry her to the hospital."

"We don't have enough help ourselves, kid!" The woman dropped some towels beside one of the bodies and moved on. "All right, all right. Bring her here if you can."

"But she needs a doctor!"

"They all do! Now, get the hell out of the way!"

He darted around bodies to the open church door. Inside, it was even more crowded, and those helping the injured looked as disheveled and harried as if they'd been at it nonstop for days. "Mister---excuse me!" he said, stopping a man. "I need help. My mother---" his voice cracked, and he felt tears starting.

The man put a hand on his shoulder. "I know, son." He gestured to the madhouse around him. "We don't have enough bandages, medicine, or anything. Until relief comes, we can't do much. Bring her here and we'll do what we can."

As the man turned to someone else, Richard realized that it was hopeless. What was one mother when there were hundreds, thousands of mothers and fathers and children hurt? He gulped down the tears and turned back to the door. With Washington so sick, with Stacey shaking with fatigue, it was up to him.

He hurried back across the street. Stacey, bent over Washington, looked up. "He passed out!" she exclaimed.

"Washington! Washington!" He shook his brother, then stood back and cried, "Oh, god! What do I do?!" He looked around wildly. He couldn't leave his brother here alone. But if Stacey stayed behind, who'd help carry the stretcher? What should he do?

"I've got to get Mom to the hospital," he cried. "There's no other way. They're full-up at the church, and they practically have no supplies. I've just got to do it. It's her only chance."

"How? She weighs as much as you do," Stacey said.

He shook her off. "See what you can do to get Washington to the church. Maybe someone there can help him. I'll try to get back to you once I get help for Mom. But if Washington feels better, come on to the hospital." He draped the white sheet, now dirty with soot and ashes, around his mother and lifted her carefully. She cried out as he almost fell backwards, then she went on whimpering. Clenching his teeth, he tottered ahead a few steps and stopped, then stumbled on across the broad boulevard strewn with debris, swaying and reeling, on and down the road leading to the hospital.

He staggered into the hospital parking lot carrying his mom's limp body. It felt as if she were glued to his arms. Sweat trickled down his face, down his neck, down his arms and legs. His breath whistled with each step. He had barely winked during the whole walk, putting all his concentration on reaching the next house, and then the next, and on and on. Finally, he saw the hospital. Standing. Not destroyed. With a cry of hope he had run the last steps and stood in the parking lot with tears streaming down his eyes, his mother's limp body still in his arms.

"Let me give you a hand, son."

He turned to the gentle voice, almost not understanding.

"It's all right. Give her to me."

He couldn't. "She's gotta have a doctor...."

"Yeah, sure. Just set her down on that mat. We'll get to her as soon as possible."

He followed meekly; eyes fixed on the back of the man with the kind voice. When they got to a small mat, he set his mother down carefully. Her yelp of pain was a knife in his heart. When she was settled, he lifted her head and shakily offered her water from his canteen. He must see that his mother got a doctor, then he'd go back and find Washington and Stacey. For the first time he lifted his eyes from his mother and took in the crowded parking lot. The scene was even more horrible than that on the lawn of the church. Speechless, he dropped to the ground beside his mother, buried his face in his hands, and burst into tears.

195Please respect copyright.PENANA6JJlGmi06a

195Please respect copyright.PENANAbZp15L9LVl

195Please respect copyright.PENANAp7ZdwBGgoq

ns 15.158.61.20da2