x

x

The Arkangel-class starship Exodus moved silently in the Priplanus Sector—a relic of a fallen empire, its once-glorious structure now a decaying ark adrift amid scattered memories. Millennia ago, a thriving planet orbited between two Earth-like worlds in this forsaken system. Its legacy now echoed in the ghostly remains of a colossal, Grecian-clad statue—a guardian of lost wisdom. For centuries, the monument had withstood the ravages of cosmic warfare, until today, when a stray shard of ancient debris shattered its enduring calm. With a sudden, haunting impact, the relic split asunder, its fragments drifting like the remnants of hope.

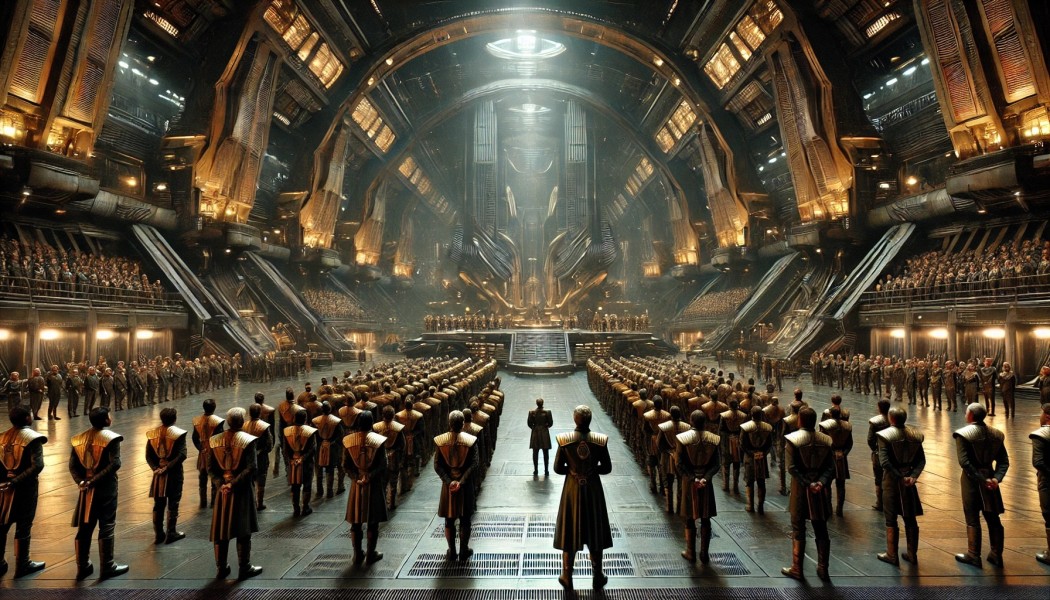

Inside the Exodus, a blend of celebration and solemn duty filled the vast, cavernous hall—once a training ground for elite defenders. Warriors from Blue One, Red One, and Yellow One had gathered. They were not leaving to explore distant worlds; they were to stand fast and protect their fragile ark against the decay that threatened to claim it.

Among them, Crispin—a determined young warrior with eyes as steady as ancient stars—exchanged a quiet word with his twin sister, Lavinia. Their bond, forged in the crucible of relentless duty, had made them inseparable. No longer merely cadets, today they were recognized as the vanguard of the Exodus’ defense.

At the front, Jaspar, the seasoned flight instructor whose wisdom had guided countless warriors, stood alongside Professor Fenn, a mentor revered for both his brilliant mind and compassionate resolve. Together, they oversaw the ceremonial simulation—a holographic tribute that rekindled time-honored traditions and bolstered the spirits of every warrior present.

The simulation burst to life on a vast projection screen, unveiling the emblem of the Exodus: a phoenix intertwined with celestial orbits. For a fleeting, humorous moment, the image glitched—its colors warping into unexpected hues—and laughter rippled through the assembly. Even amidst the gravitas of their duty, a spark of levity endured.

"It's a curious thing, isn't it—leaving behind the old ways?" Crispin murmured to Lavinia, his voice rich with wistful nostalgia yet underpinned by the steady resolve of a true guardian.

Lavinia offered a gentle smile and said, "Crispin, our legacy lives within us. Each breath we take honors the memory of what has been and secures the promise of what may yet come."

Their words resonated with every warrior. In this new order, every assignment was a pledge to protect the Exodus. Crispin had been appointed to Central Defense Command—a role demanding unwavering vigilance—while Lavinia, affectionately known among her peers as Doctor Gentry, had been entrusted to the Science and Recon Unit, where her keen intellect would safeguard the ark’s fading lore.

Jaspar strode through the crowd with effortless cool, extending firm handshakes as he went. "Blue One," he declared with a blend of wry confidence and resolute pride, "it's an honor to stand with you—the steadfast guardians of our ark."

A murmur of determination pulsed through the hall. Amid the celebration, a subtle tension lay over every word: the Exodus was deteriorating, and its survival depended on the courage and skill of its defenders.

Suddenly, a crisp command rang out over the intercom in the clear, steady voice of Deputy Oberon: “Jaspar, Saphira—report to the bridge immediately.”

Jaspar’s eyes flashed with determination as he replied, “Understood, Deputy.” Turning back to the assembly, he declared, “Today, we are not just warriors in training—we are the officers charged with protecting our only home.”

A ripple of approval passed among the ranks. Amid laughter, heartfelt greetings, and the busy hum of preparations, an ominous shadow loomed beyond the celebration. In the dark expanse of space, Magnus Voss, the enigmatic leader of the Obsidian Order, observed with cold calculation. His dark designs threatened not only the Exodus, but the fragile hope that sustained its defenders.

As the convocation drew to a close, the warriors—united by honor, kinship, and the heavy burden of duty—advanced toward the bridge. Their footsteps echoed in the cavernous halls as they prepared to confront the looming darkness, the legacy of a fallen empire burning in their hearts.

“Blue One!” called Professor Fenn, and the warriors moved as one—a single force, steadfast and resolute, ready to defend the ark against the night.