x

x

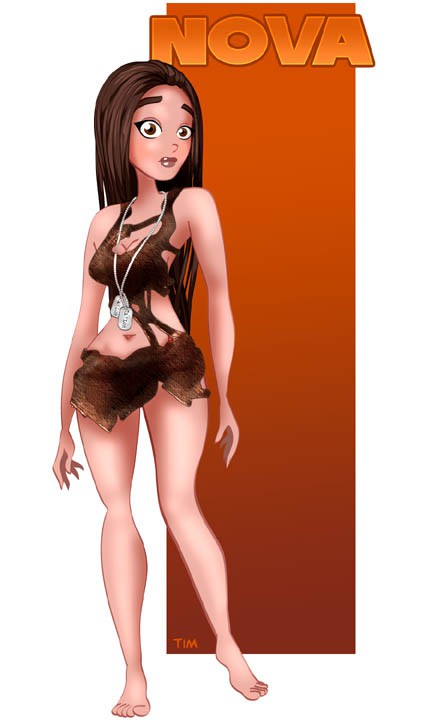

"She can only be a female savage," I said, "belonging to some backward race like those found in New Guinea or in our African forests."

I had asked without the slightest conviction. Denis Petrov asked me, almost violently, if I had ever noticed such grace and fitness of feature among primitive peoples. He was one hundred times right and I could think of nothing else to say. Professor Kaminski, who seemed to be lost in thought, had nevertheless listened to our conversation.

"Even the most primitive people on our planet have a language," he finally said. "That woman cannot talk."

We searched for the stranger around the region of the stream, but we were not able to find the slightest trace of her, so we made our way back to our launch in the clearing. The professor thought of taking off again to attempt a landing at some more civilized spot, but Petrov suggested stopping where we were for at least 24 hours in order to attempt another contact with the denizens of this jungle. I supported him in this suggestion, which eventually prevailed. We darked not admit to each other that the hope of seeing the girl again held us rooted to the area.

The afternoon passed incident-free; but towards evening, after admiring the fantastic setting of Chang-Er, which flooded the horizon beyond the human imagination, we had the impression of some change in our surroundings. The jungle gradually came alive with stealthy rustlings and snappings, and we felt that invisible eyes were spying on us through the foliage. We spent an uneventful night, however, barricaded in our launch, keeping watch in shifts. At daybreak, we experienced the same sensation, and I fancied that I heard some shrill little cry like those Novaya had uttered the other day. But none of the creatures with which our feverish imagination peopled the forest revealed themselves.

We decided to return to the waterfall. The whole way, we were obsessed by the unnerving impression of being followed and watched by creatures who refused to reveal themselves. Yet Novaya, the previous day, had been willing to approach us.

"Maybe it's our clothing that frightens them," Denis Petrov said suddenly.

This seems like the most likely explanation. I distinctly remembered that when Novaya had fled after strangling our chimp, she had found herself in front of our pile of clothes. She had then sprung quickly aside to avoid t hem, the way a shy horse might.

"We'll find out soon enough."

And diving into the lake after disrobing, we began playing again as on the day before, ostensibly oblivious of all that surrounded us.

The same trick worked again. After a few minutes we noticed the girl on the rocky ledge, without having heard her approach. This time, however, she did not return alone. A man was standing beside her, a man built like us, resembling men on Earth, a middle-aged man also totally naked, whose features were so similar to those of our goddess that I presumed him to be her father. He was watching us, as she was, in an attitude of bewilderment and concern.

And then there were others. Little by little we noticed them, as we forced ourselves to maintain ourselves to maintain our pretended indifference. They crept stealthily out of the forest to gradually form an unbroken circle around the lake. They were all sturdy, handsome specimens of humanity, men and women with golden skin, now looking restless, evidently prey to a great excitement and uttering an occasional sharp cry.

We were hemmed in and felt somewhat anxious, the incident with Nicholas still fresh in our minds. But their attitude was not menacing; they just seemed to be curious about our actions.

That was it. Presently Novaya, Novaya whom I already regarded as an old friend---slipped into the water and the others followed one by one with varying degrees of hesitation. They all drew closer, and we began to chase one another in the manner of seals as we had done the previous day only this time we were surrounded by a score, maybe more, of these bizarre creatures, splashing about and playing all with solemn expressions contrasting strangely with these absurd frolics.

After a quarter of an hour of this I was starting to grow numb and tired. Was it just to behave like schoolchildren that we had come all the way to the universe of Chang-Er? I felt almost ashamed of myself and was vexed to see that the learned Kaminski appeared to be taking great pleasure in this game. But what else could we do? One cannot easily imagine the difficulty of making contact with these creatures who are ignorant of the spoken word or of laughter. Yet I did my best. I went through a few motions that I hoped might convey some meaning. I clasped my hands in as friendly a manner as possible, bowing at the same time, in the traditional Japanese manner. I waved kisses at them. None of these gestures, I am sorry to tell you, evoked the least response. Not a glimmer of understanding appeared in their eyes.

Whenever we had discovered, during the voyage, our eventual encounter with living beings, we saw in our mind's eye monstrous, misshapen creatures of a physical aspect radically different from ours, but we always implicitly imagined the presence in them of a mind. On the planet Silarous reality seemed to be quite the reverse: we had to do with natives resembling us in every way from a physical standpoint yet who seemed to be totally devoid of the power of reason. This indeed was the meaning of the expression I'd found so disturbing in Novaya and that I saw now in the others: a lack of conscious thought; the absence of intelligence.126Please respect copyright.PENANA10OM3nvXq4

They were interested in nothing by playing. And even then, the game had to be pretty simple! We were forced to introduce it into a semblance of coherence that they could grasp, the three of us linking hands and, with the water up to our waists, shuffling around in a circle, raising and lowering our arms together the way small children might do. This seemed to move them not in the slightest. Most of them drew away from us; others gazed at us with such an obvious absence of comprehension that left us dumbfounded ourselves.

It was the intensity of our dismay that was the root cause of the tragedy. My God! Here we were, three grown men, one of whom was a world celebrity, holding hands while executing a childish dance under the mocking eye of Chang-Er, that we were unable to keep straight faces. We had undergone such restraint for the last quarter of an hour that we needed some relief. We were overcome by fits and gales of wild and uncontrollable laughter.

This explosion of hilarity finally awakened a response in the onlookers, but unfortunately it was not the one we had been hoping for. A kind of tempest ruffled the lake. They started rushing off in all directions in a state of fright than in other circumstances would have struck us as laughable. After a few moments we found ourselves all alone in the water. They ended up by collecting together on the bank at the edge of the pool, in a trembling mob, uttering their furious little cries and stretching their arms out towards us in rage. Their gestures were so menacing that we took fright. Petrov and I made for our assault rifles, but the wise Kaminski whispered to us not to use them and even not to brandish them so long as they didn't approach us.

We dressed quickly without taking our eyes off of them. But barely had we put on our trousers and shirts than their agitation grew into a frenzy. It seemed that the sight of men wearing clothes was unbearable to them. Some of them took to their heels; others advanced towards us, their arms outstretched, their hands clawing at the air. I picked up my assault rifle. Paradoxically for such obtuse people, they seemed to grasp the meaning of this gesture, turned tail, and vanished into the trees.

We made haste to reach the launch. On our way back I had the impression they were still there, albeit invisible, and were following our withdrawal in absolute silence.

126Please respect copyright.PENANAWEdSNIT7xv

126Please respect copyright.PENANAQVBiWDkB4P

ns18.117.157.126da2