x

x

With Gorbachev resigning as President of the USSR, the remaining republics including Kazakhstan, Belarus and Russia, declared their independence and the Soviet Union ceased to exist on December 31, 1991. This dissolution complete, all the safeguards that had previously kept Zarmaria and Shamajar at peace disappeared and a full-scale war erupted between the two countries. Untold thousands were killed or wounded.

The fighting continued until the Zarmarians captured the strategically important town of Shikhu. The two sides surprised the world by agreeing to a ceasefire deal on May 9, 1994, the prize, Mochi-Jojeji, going to Zarmaria. Since then, the territory had settled down, the hand of the Zarmarian government's hand greatly strengthened by the construction of several major highways to like them with their brother republics. There had been a few border incidents, brawls breaking out between rival ethnic groups, but no more so, apparently than in, say, Israel's West Bank. All seemed set fair for the coming years in this part of the world.

But there were rumors.

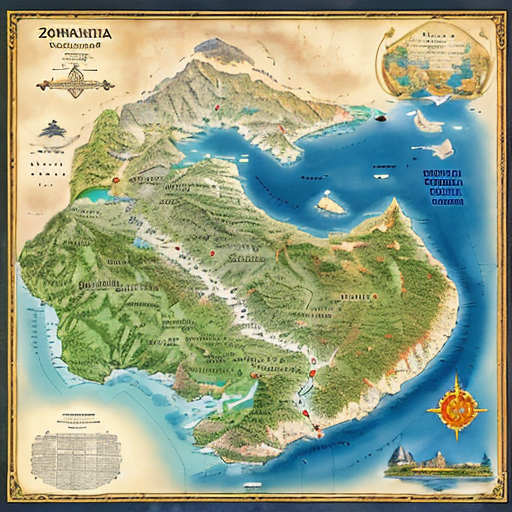

I read papers, studied maps and figures, and on the surface, this was a textbook operation. I crammed in a lot of appointments, trying to have at least a few words with anyone who was directly concerned with the Mochi-Jojeji business. For the most part these were easy, the people I wanted to see being all bunched up close together in the capital; but there was one exception, and an important one. I talked to Beauregard about it first.

"Isn't Herolutions Ltd. a major military contractor? Why them? This isn't a military operation."

Beauregard explained. British Aerospace had part ownership of one company that specialized in making heavy-duty, high-tech vehicle maker, a firm with considerable overseas experience and well under the thumb of the Board, but they were currently occupied with other work. There were few other British firms in the same field (the majority being American), and Beauregard had tendered the job to a Canadian American company, but in the end the contract had gone to someone who seemed to be inappropriate for the business. I asked if some kind of shady deal had been made behind his back."

"Oh, good heavens, no," Beauregard said. "This crowd has good credentials, a good track record, and their price is damned competitive. There are too few firms about who can make the kind of vehicle we need, and their prices are getting out of hand---even our own. I'm willing to encourage anyone if it will increase competition."

"Their price might be right for us, but is it right for them?" I asked. "I don't see them making much money on this."

It was vital that no firm that worked in tandem with us ever come out badly. British Aerospace had to be a crowd whom others were anxious to be alongside. And I was far from happy with the figures that Herolutions was quoting, attractive though they might be to Harper and Beaumont.

"What are they doing over there?"

"They're there because they know their job. It's a splinter group from Clifton Cloverprises and we think the best of that bunch went to Herolutions when it was set up. Their main man is a youngish chap, Andy Hale, and he took Cliff Giles with him for starters."

I knew both those names, Hale only as a noise but Giles and I had met before on a different kind of job. That one was simply a matter of moving a giant electrical transformer from the British industrial midlands up to Scotland; no easy matter but a cakewalk compared with moving a satellite through two emergent and barely developed nations. I wasn't aware that Herolutions had any overseas experience, so I decided to find out for myself.

To meet Hale, I drove up to Accrington-on-Thames and was mildly startled at what I found when I got there. I was all for a brother company ploughing its finances into the heart of the business rather than setting up fancy offices and shop front prestige, but to find Andy Hale running a show from a prefab shed right in amongst the workshops and garages was disturbing. Herolutions had, for some reason, set up something made of string-and-brown paper and Beauregard was crazy enough to be proud of it!

But I was impressed by him and his paperwork and couldn't find fault with either. I had wanted to meet Hale again, only to be told that he was already in Zarmaria with his foreman and crew, waiting for the arrival of the rig, the Stardust, by train. Hale himself intended to fly out when the Stardust was ready for its first run, a prospect which clearly excited him: he was in the '90s equivalent of the New World, where no one had ever been before. I tried to steer a course midway between scaring him with examples of how different his job would be from anything he had ever experienced before, and overboosting his confidence with too much enthusiasm. I still had doubts, but I left Accrington-on-Thames and later Heathrow with a far greater optimism than I'd have thought possible.

On paper, everything was splendid. But I've never known events to be transferred from paper to reality without something being lost in the translation.

Dunin was hot and sweaty. The temperature was climbing up to the hundred mark and the humidity was struggling to join it. Brian Tipton met me at the new airport, what had once been a Soviet Air Force based: runways that originally took bombers now took jumbos and it had a concourse three times the size of Penn Station. It was large enough to serve a city the size of, say, Rome.

A chauffeur driven car awaited outside the arrivals building.

I got in with Tipton and felt the sweat break out under my armpits, and my wet shirt already sticking to my back. I unbuttoned the top of my shirt and took off my jacket and tie. I had suffered from cold at Heathrow and was overdressed here---a typical tourist's nightmare. In my case was a superfine lightweight safari suit by Huntsman---that was for hobnobbing with Cabinet ministers and suchlike---and two desert camouflage jumpsuits. For the rest I'd by local gear and probably dump it when I left. Cotton shirts and shorts (these days made in China by slave labor) were always easy to get hold of.

I sat back and watched the country flow by. I hadn't been deep into the heart of what had once been the USSR before, but it wasn't much different from Russia, the Mongolian steppes, or any other Eurasian landscape. Personally, I liked the less lush bits of Asia, the scrub and semi-desert areas, and I knew I'd be seeing plenty of that later on. The advertisements for Schwinn Bicycles and Lipton Tea proclaimed a new kind of Western imperialism, that of the commercial kind, although those for Coca-Cola were universal and had flourished even under communism.

It was early morning and I had slept on the flight. I felt wide awake and read to go, which was more than I could say for Tipton. He looked tired, and I wondered how hard it was getting for him.

"Do we have a company plane?" I asked him.

"Yes, and a good pilot, a Ukrainian." He was silent for a while and then said cautiously, "Funny meeting we had last week. I was pulled back to London at 12 hours' notice and all that happened was that we sat around telling each other things we already knew."

He was fishing and I knew it.

"I didn't know most of it. It was a briefing for me."

"Yes, I rather guessed as much."

I asked, "How long have you been a company man?"

"Seven years."

I'd never met him before, or heard of him, but that wasn't unusual. It's a big outfit and I met new faces constantly. But Tipton would have heard of me, because my name was trouble; I was the hatchet man, the expediter, sometimes the executioner. As soon as I showed up on anyone's territory there would be that tightening feeling in the gut as the local boss man wondered what the hell had gone wrong.

I said, to put him at his ease, "Relax, Brian. It's just that Beauregard's got ants in his pants. Trouble is they're invisible ants. I'm just here on an interrupted vacation."

"I'm sure you are," Tipton said, not believing a word of it. "What do you want to do first?"

"I think I want to go up to the site at Sutovo for two days, use the plain and overfly this road of theirs. After that I might want to see someone in whatever's passing for the government here. Any suggestions?"

Tipton stroked his jaw. He knew that I'd read up on all of them and that it was quite likely I knew more about the local scene than he did. "There's Iskrai Muirairraiel--he's Minister for the Interior, and there's the Treasury Minister, Absem Runluaiel. Either would be a good starting point. And I suppose Denerhaiel will want to throw his hat in the ring."

"What's he supposed to be? The local Goebbels?"

"As a matter of fact, yes. He's the Minister for Misinformation."

I grinned and Tipton relaxed a little more. "Who's got the itchiest palm? Or by some miracle are none of them on the take?"

"No miracles here. As for which one is the greediest, that I don't know. But, in this nation of farm workers, I'm sure you'll be able to buy a few tidbits of information from almost anyone."

We were as venal as the men we were dealing with. There was room for a certain amount of honesty in my profession but there was also room for the art of wheeling and dealing, and frankly I rather liked that. It was fun, and I didn't ever see why making one's living had to be a joyless occupation.

I said, "Right. Now, don't tell me you don't have any problems. You wouldn't be human if you didn't. What's the biggest headache on your list right now?"

"The satellite itself."

"Herolutions? What the hell's going on?"

"Well, the satellite is scheduled to leave a week from the day but the train carrying the Starduster hasn't arrived yet. She's on board a special freight train, not on a regular run, and she's being held up in Turkey. Customs problems, they tell me. Herolutions' foreman is here and he's fairly sweating bullets. He's been going up and down the road checking gradients and tolerances and he's not too happy with some of the things he's seen. He's back in town now, ready to supervise the unloading of the Starduster."

"The satellite?"

"Oh, the solar panels and instrument package are all OK. But they're impossible to carry up on a Land Rover. Do you want to meet him right away?"

"No, I'll see him when I come back from Sutovo. No point in our talking until there's something to talk about. And the non-arrival of the Starduster isn't a topic."

I was telling him that I wasn't going to interfere in his job, and it made him happier to know it. We had been traveling up the sunny side of a gentle mountain and now emerged into a maze of stark, foreboding high-rises shooting up on both sides of our car like the gruesome trees of some Brothers' Grimm fairy tale. Unlike in Western cities, these buildings were not designed to adorn each other. There was no evidence of recreation here, either. Dunin was a city of monotony and boredom, no paragon of classical beauty that would have been missed in a US/USSR nuclear war.

We wove through the haphazard traffic and stopped at one of the last remaining bits of Soviet architecture in sight, complete with peeling paint and sagging wooden balconies. It was, I am sorry to say, my hotel."

"I had a bit of a job getting you a room," Tipton said, thus letting me know that he wasn't without the odd arm to twist.

"What's the attraction? This place is hardly any kind of tourist's Mecca."

"Of course not! The attraction is money, the chance to help an adolescent country grow up. You'll find Dunin is full of businessmen and missionaries from all over the world, particularly Americans. The government has been eclectic in its franchises."

As the car pulled up, he went on, "Can I do anything for you right now?"

"Nothing for today, Brian, thanks. I'll book in and get changed and cleaned up, do some shopping, take a stroll. Tomorrow I'd like a car here at 7:30 to take me to the airport. Are you free this evening?"

Tipton had been anticipating that question and indicated that he was indeed available. We arranged to meet for a drink and a light meal. Any of the things I'd observed or thought about during the day I could then try out on him. Local knowledge should never be neglected.

By nine the next morning I was flying along the coast following the first 200 miles of road to Khentulga where we were to land for refueling before going on into Mochi-Jojeji. There was more traffic on the road than I would have expected, but far less than a road of that class was designed to carry. I took out the small pair of binoculars I carried and studied it.

There were a few saloons and four-wheel drive vehicles, Suzukis and Land Rovers, and a fair number of junky old Soviet-era trucks. What was more surprising was the number of big trucks; thirty- and forty-tonners. I saw that one of them was carrying a load of electrical cable. The next was a bucket truck, then another, carrying from the trail it left, excavation mud. This traffic was technology-generated and was laying down infrastructure from Dunin southwestward to Shamjara.

I said to the pilot, a cheerful young man called Artem Sirenko, "Can you fly to the other side of Khentulga, please? Not far, say twenty miles. I want to look at the road over there."

"Ach, road peter out one mile, think more, beyond the town. But, for you, I go on," he said.

And, true to Artem's words, the road indeed vanished into the miniature build-up around Khentulga, reemerging inland from the coast. On the continuation of the coastal stretch another road carried on southwards, less impressive than the earlier section but apparently perfectly usable. The little train station didn't look too busy, but there were two or three fair-sized trains idling in the nearby rail yard. Not easy to tell from the air, but it didn't seem as if there was a building in Khentulga higher than three stories. The endless frail smoke of shantytown cooking fires wreathed all about it.

Refueling was done quickly at the airstrip, and then we turned inland. From Khentulga to Sutovo was about 800 miles and we flew over the broad strip of concrete thrusting incongruously through bogs, pine-tree forests, savannah and the scrubby fringes of desert country. These new "roads" were being built by Italian engineers, Japanese surveyors and a mixture of road crews with Russian money and they were costing twice as much as they should, the surplus being siphoned off into a hundred (or more) unauthorized pockets and numbered accounts in Swiss banks----a truly international venture.

The Russians were not perturbed by the way their money was being used. They were not penny-pinchers and, in fact, were working to see that some of the surplus money went into the right pockets. It was a cheap way of buying friends in newly independent nations---a carryover from the heady days of the Cold War when many countries, poised uncertainly, were ready to fall East or West in any breeze. In reality, Zarmaria and Shamajar were just more pieces laid on the chessboard of international diplomacy.

The road drove through thick forest and then heaved itself up towards the sky, climbing the hills which edged the central plateau. Then it crossed the sea of grass and bush to the dry region of the desert and came to Sutovo where the towers of cranes made a new forest, one of steel.

I spent two days at Sutovo talking to the men and the bosses, scouting about the workings and cocking an ear for any kind of unrest or uneasiness. I found very little worthy of note and nothing untoward. I did have a complaint from Wayne Lyon, the chief engineer, who had been sent word of the change of schedule and didn't like it.

"I'll have thirty steel fitters playing poker when they should be working," he said abrasively. "Why the bloody hell did they have to send the satellite pieces first?"

It'd all been explained to him, but he was being hateful. I said, "Chill out. It's all been authorized by Beaumont from London."

"London? What the hell do they know about it? This Beaumont doesn't understand the first damn thing about it," he said. Lyon wasn't the man to be mealy-mouthed. I calmed him down---well, maybe halfway down---and went in search of other problems. It worried me when I couldn't find any.

On Day 2 I had a phone call from Beaumont. On a crackling line full of static and clashing crossed wires his voice said faintly, ".....Having a meeting with Muirairraiel and Denerhaiel. Do you want...?"

"Yes, I do want to sit in on it. You and who else?" I was shouting.

"....Giles from Herolutions. Tomorrow morning..."

"Has the Starduster come?"

"....Unloading....came yesterday. I'll be there."

The meeting was held in a cool room in the Retributive Justice Center. The most important government man there was the Minister of the Interior, Iskrai Muirairraiel, who presided over the meeting with a bland smile. He did not say much but left the talking to a short, slim man who was introduced as Rolan Denerhaiel. I couldn't figure out whether Muirairraiel didn't understand what was going on or understood and didn't give a shit: he displayed a splendid indifference.

Very surprising for a meeting of this kind was the presence of one Major General Tadur Ecnacshaiel, the army boss. Although he was not a member of the government, he was a living reminder of Mao's dictum that power grows out of the muzzle of a gun. No Zarmarian government could live without his nod of approval. At first, I couldn't see where he fitted into this discussion on the moving and launching of a satellite.

On our side there was me, Tipton, and Cliff Giles, who was a lean Englishman with a thin brown face stamped with tiredness and worry marks. He greeted me pleasantly enough, remembering our last encounter some few years before and appearing unperturbed by my presence. He likely had too much else on his plate already. I let Tipton make the running and he addressed his remarks to the Minister while Denerhaiel did the answering. It looked remarkably like a ventriloquist's act, but I found it hard to figure out who was the dummy. Ecnacshaiel kept an overbearing silence.

After some amiable chitchat (not the weather, thank God) we got down to business and Tipton outlined some routine matters before drawing Giles into the discussion. "Could we have a map, please, Mr. Giles?"

Giles placed a map on the big table and pointed out his bottlenecks.

"We have to get out of Dunin and through Khentulga. Both are big towns and to take something like this through presents difficulties. It's been my experience in Europe that operations like this draw the crowds and I can't see that it will be different here. We should appreciate a police escort."

Denerhaiel nodded. "It will most assuredly draw the crowds." He seemed pleased.

Giles said, "In Europe we usually take these things through at extreme off-peak times. The small hours of the night are often best."

This remark drew a frown from Denerhaiel and I thought I detected the slightest of headshakes from the Minister. I became more alert.

Ecnacshaiel stirred and spoke for the first time, in a deep and beautifully modulated voice. "You will certainly have an escort, Mr. Giles---but not the police. I am putting an army detachment at your service." He leaned forward and pressed a button, the door of the room opened, and a smartly dressed officer strode towards the table. "This is Captain Dezi Checnecaiel who will command the escort."

Captain Checnecaiel clicked to attention, bowing curtly, and then at a nod from Ecnacshaiel stood at ease at the foot of the table.

Denerhaiel said, "The army will accompany you all the way."

"Won't you be breaking the cease-fire if you do that?" Tipton asked.

"The Shamaris will understand, I promise you."

I sensed that Tipton was about to say something off-color and forestalled him. "We are more than honored, Major General. This is extremely thoughtful of you, and we appreciate it. It's more of an honor than such work as this usually entails."

"'Our new police force is small, underfunded, and quite overburdened. We regard the safekeeping of such expeditions as these of the greatest importance, Mister Tipton. The army stands ready to be of any service." He was very smooth, and I guessed that we'd come out of that little encounter on level ground. I prepared to enjoy myself

"Please explain the size of your command, Captain," Denerhaiel said.

Checnecaiel had a soft voice that clashed with his appearance. "For work on the road I have four infantry troop carriers with six men to each carrier, two trucks for logistics purposes, and my own staff car, plus outriders. Eight vehicles, six motorcycles and thirty-six men including myself. In the towns I am authorized to call on local army units for crowd control."

Wow! He was bringing up the big guns with a vengeance. Just how important was the Starduster to require that kind of escort, whether for crowd control of any other safety regulations? Wasn't this usually done in wartime conditions? My curiosity was aroused now, but I said nothing and let Tipton carry on. Taking his cue from me he expressed only his gratitude and none of his perturbation. He'd expected a grudging handful of ill-trained local cops at best.

Checnecaiel was saying, "In the Zarmarian army, the rank of captain is relatively high, gentlemen. You needn't fear being held up in any way."

"I'm not," said Giles politely. "It will be a pleasure having your help, Captain. But now there are other matters as well. I am sorry to tell you that the roads have deteriorated slightly in some places, and my satellite might be too heavy for them."

Well, that was certainly an understatement, but Giles was working hard at diplomacy. Obviously, he was wondering if Ecnacshaiel had any idea of the demands may by heavy transport, and if army escort duty also meant army assistance. Ecnacshaiel picked him up and said, easily, "Captain Checnecaiel will be authorized to negotiate with the civil bodies in each area in which you may find difficulty. I am sure that an adequate labor force will be found for you. And, of course, the needed materials."

It all seemed too good to be true, but this didn't stop Giles from moving on to the next issue. "Crowd control in villages is only one aspect, of course, gentlemen. There is the sheer difficulty of pushing a big vehicle like Starduster through a town. Here on the map is an outlined proposed route through Dunin, direct from the train station to the outskirts. I estimate it will take eight, perhaps nine hours to get through the red line marks the simplest, in fact, the only route, and the figures in circles are the estimated times at each stage. That should help your traffic control, although we shouldn't have too much trouble there, moving through the central city area mostly during the night."

The Minister made a sudden movement, wagging one finger sideways. Ecnacshaiel glanced at him before saying, "It won't be necessary to move through Dunin at night, Mr. Giles. We would rather you made the move in daylight."

"That'll disrupt your traffic flow considerably," said Giles in some surprise.

"That does not matter to us. We can handle it." Ecnacshaiel bent over the map. "Why does your route lie through Boagırlsıkrınn Square?"

"There's no other way," Giles said apologetically. "Starduster doesn't bend, therefore making it impossible to move through this tangle of narrow streets on either side without a good deal of damage to buildings."

"You are correct," said Ecnacshaiel. "In fact, had you not suggested it we would have asked you to go through the Square ourselves."

This seemed to come as a wholly novel idea to Giles. I could see he was thinking on the squalls of alarm from the London Metropolitan Police had he suggested pushing a gigantic 300-ton futuristic truck through Trafalgar Square in the middle of the rush hour. Wherever he'd worked in Europe, he'd been bullied, harassed and crowded into corners and sent on his way with the stealth of a thief.

He paused to take this in with one finger still on the map. "There's another very real difficulty here, unfortunately. This big plinth in the middle of the avenue leading into the Square. It's sited at a very bad angle from our viewpoint---we're going to have a hell of a time getting around it. I would like to suggest...."

The Minister interrupted him with an unexpected deep-bellied, rumbling chuckle but his face remained bland. Ecnacshaiel was also smiling and in his case, too, the smile never reached his eyes. 'Yes, Mister Giles, we can see that. You need not trouble yourself about the plinth. We will have it removed. It will improve the flow of traffic into I don't think you need trouble about the plinth. We will have it removed. It will improve the traffic flow into Zoarom Avenue considerably in any case."

Giles and Tipton exchanged fast glances. "I....I think it may take time," said Tipton. "It's a big piece of masonry."

"It is a task for the army," said Ecnacshaiel. "Take care of it, Captain."

Checnecaiel nodded and made fast notes. The discussion continued, the exit from Dunin was detailed and the progress through Khentulga dismissed, for all its obvious difficulties to us, as a mere nothing by the Zarmarians. About an hour later, after some genteel refreshment, we were finally free to go our way. We all went up to my hotel room and could hardly wait to get there before indulging in a thorough postmortem of that extraordinary meeting. It was generally agreed that no job had ever been received by the local officials with greater cooperation, any problem melting like snowflakes in the hot Dunin sunshine. Paradoxically it was this very ease of arrangement that made us all nervous, especially Cliff Giles."

"I can't believe it," he said, not for the first time. "They just love us, don't they?"

"I think you've put your finger on it, Cliff," I said. They really need us and they're going out of their way to show it. And, from what I know of both countries, they're little better than their former Russian masters when it comes to running roughshod over the needs and wishes of their populaces. They're going to shove us into the oven in the middle of broad daylight, and the hell with anything or anybody else."

"Like a cease-fire," said Tipton.

Giles said, "I think we're missing something here, something we all need to look at more closely."

Tipton chuckled nervously. "This job certainly does seem to have a definite undercurrent, one that we've been too busy to pay attention to---until now. Now, what are we dealing with here, anyway? Is it some local bigwig who is looking for just the right excuse to start a new war over that godless piece of real-estate? Take a moment to look at things from Ugurnaszirev's perspective, if you will. What is the loss of Mochi-Jojeji to Zarma? It must have been a big humiliation, so big, in fact, that I'll bet the poor chap pooped in his breeches while still seated at the negotiating table. One does not get over a profound disappointment like that, you know. Not ever!"

445Please respect copyright.PENANAggiatSgrs2

445Please respect copyright.PENANA1NVzC0eeFZ

445Please respect copyright.PENANAL3AV4ccJhk

445Please respect copyright.PENANAzLln7B2Wrw

445Please respect copyright.PENANA98DQZo7VXt

445Please respect copyright.PENANADB1E8GFJnd

445Please respect copyright.PENANAXUtFcbntrQ

445Please respect copyright.PENANA9lLS7Q3J8j

445Please respect copyright.PENANACRDJ47lugI

445Please respect copyright.PENANAW85nsNb7CT

445Please respect copyright.PENANAIHsEqsTjd5

445Please respect copyright.PENANAiQN4713On3

445Please respect copyright.PENANArnJOZNmm5t

445Please respect copyright.PENANAfS9ZSm2qmP

445Please respect copyright.PENANAWc1XICbYTn

445Please respect copyright.PENANAUefQgnlGqI

445Please respect copyright.PENANApPfBWSyeeD

445Please respect copyright.PENANAlqMuAjYOjK

445Please respect copyright.PENANAZ6lWrdO4so

445Please respect copyright.PENANABvqixLJtmQ

445Please respect copyright.PENANAycc01kqiuL

445Please respect copyright.PENANA3fEL4dAg8A

445Please respect copyright.PENANAkVhxJEHaUC

445Please respect copyright.PENANA4THrKgcArx

445Please respect copyright.PENANAPPQnxAhJyY

445Please respect copyright.PENANAdmokrH8ib5

445Please respect copyright.PENANArLxT6Df4Fc

445Please respect copyright.PENANAe0JIafVgMk

445Please respect copyright.PENANAkq5cuhKwiZ

445Please respect copyright.PENANA23CIOYSgEL

445Please respect copyright.PENANARMDj11iPiK

445Please respect copyright.PENANAfUVjdtIV7T

445Please respect copyright.PENANA0NkqHQDmUK

445Please respect copyright.PENANALsvl8bX0lE

445Please respect copyright.PENANADEvPuAHhxk

445Please respect copyright.PENANAwGAK1mIKrb

445Please respect copyright.PENANAYqSfez07Ek