x

x

LOS ANGELES, CA.

568Please respect copyright.PENANArw349QB8yv

Kathy Lakas humped her suitcase up the stairs, opened the door to her apartment, and found five of the seven committee members waiting for her in her living room.

"I hope you don't mind, Kathy," Larry apologized. "It was important that we meet and your landlord let us in."

Kathy shrugged. "Make yourselves at home. So, what brings you guys here?"

"We asked you to call off that mercenary. Instead, we find out that you've talked him into going back to Harborview. Why?"

"There's still a chance he'll find a way to rescue Mischa Barton, Matt," she accused, "you've been influencing them."

Matt nodded. "They share in our responsibility, therefore they had a right to know."

"After what's happened in Harborview," Larry cut in, "we don't want the responsibility for the mercenary's death---nor do we want the responsibility for anyone he might kill. We resigned ourselves to a minimum of violence to achieve what we believe is an important social objective. But in using this guy, Dragov, we're already in way too deep. I told you before and now the committee is instructing you: call him off, tell him there's no contract. If he's in Harborview, get him out of there as soon as you can."

"What happens to the committee then?" Kathy asked. "Are we just going to rot?"

"No, Kathy, of course not," Borgas protested. "We haven't abandoned Ms. Barton. It's just that we're backing off from direct action. We'll still petition and canvass and put pressure where we can. We'll campaign for human rights harder than ever before---but peacefully."

"Peacefully---you're going to get a woman like Mischa Barton out of Pescadero peacefully! That's bullshit and you know it," Kathy exploded angrily. "People have been trying to free their loved ones from the godforsaken place for over fifty years." She felt betrayed by her colleagues.

"We've just got started on the only course left open to us and already you're running scared," she said bitterly. "We've been all over the morality of what you're doing---I thought you felt deeply enough about this, that you cared enough to take the risks."

"Oh, spare us, Kathy," Larry said. "We care, sure we care, that's why we formed this committee, but we've had our wars. We've got our careers and our families on the line. It's clear to us all now that we should never have let you talk this committee into taking direct action."

"And Mischa Barton and all that bullshit we believed about finding a new direction, a new catalyst to unite liberal consciousness," Kathy asked, "what'll we do with that now?"

"I'm not saying your way won't work," Borgas answered her from across the room. "I'm not even arguing the morality of using a mercenary. But think about it, Kathy. If this goes sideways, and I'm involved in any way, it's not just my career on the line. It's my life. Do you understand?" he blustered. "Call that contract off."

"O.K.," Kathy said, despising them, knowing that Dragov had read them right all along and almost preferring the mercenary's morality to theirs. "I'll do it alone."

"You can't be serious?" Matt exclaimed, startled. "You can't go anywhere without us. Where'll you find the money to pay him?"

"I'll find it," Kathy replied stubbornly. "When I started this I meant to see it through. And if Dragov finds a way to get Ms. Barton out of Pescadero, I'll back him. I'll resign from the committee and I'll take full responsibility for what happens."

Kathy opened the door. The committee members filed silently out of the room. Borgas stopped in front of Kathy, "You're a very stubborn woman," he said, "but let me tell you, when you mix with killers, whatever your good intentions, the violence will eventually come home."

Matt stayed behind.

"Get the hell out of my face, Matt," Kathy said.

"No, not until you get a little sense," Matt replied. "You can't possibly employ a mercenary and go against a place like Pescadero on your own."

"I'm not on my own, I've got my brother with me on this and if there's a way, we're going to do it." Kathy collapsed tiredly into a chair, faltering for a moment. "Oh God, Matt," she said, her resolution faltering for a moment, "we were part of a generation that brought down a president when he tried to change the course of American society, what's happened to us? Whatever happened to our courage?"

"That was a long time ago now,' Matt answered her gently. "You heard Larry; we've made our statements, paid our dues. We're naturalized citizens, with all the rights, privileges, and responsibilities thereunto pertaining. You're still fighting and you've got what it takes, but you don't have as much to lose as we do."568Please respect copyright.PENANAJfq3ZUVSUv

568Please respect copyright.PENANAHERAOCpDUB

568Please respect copyright.PENANABjUQMcw3Vx

568Please respect copyright.PENANALz1mRmOzdT

568Please respect copyright.PENANAJyFec8eZcl

568Please respect copyright.PENANAcCThlWTbtt

After leaving Harborview, Dragov decided to lay low in Los Angeles for a while, allowing the heat from his recent ordeal to dissipate. He remained in the city for several weeks, cautiously monitoring his surroundings and avoiding potential risks. Once he felt it was safe to proceed, he booked a flight from Los Angeles to Paris. His route involved traveling to Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) and boarding a direct flight to Paris to Charles de Gaulle Airport (CDG).

A taxi set him down on the Rue St. Louis en L'ile before a narrow doorway with a number almost eaten away by age. The door was open; he checked the names on a row of mailboxes and climbed the steep stairway to the fourth floor. After a few moments a stocky, bespectacled, bearded man opened the door.

"You Viktor Dragov?" he said. "I'm Michael Lakas." He was a few years older than Kathy and possessed the same direct manner. "My sister called, I've been expecting you, come in."

Dragov followed Michael Lakas into a small but very comfortably furnished apartment.

"Do I continue with this contract," Dragov asked immediately, wanting to know where he stood, "or has your committee decided to terminate it?"

"We're still picking up your expenses," Michael replied, "and I've got a message for you from Kathy. She needs to know how much a rescue, if it's possible, could cost."

"Tell her I have no possible way of knowing at this point," Dragov answered, "but if it can be done, then she can tell her committee that it is unlikely to cost less than two hundred and fifty thousand U.S. dollars."

"Two hundred and fifty thousand dollars?" Michael exclaimed, his shock evident in his voice.

"The challenges of Pescadero make it a very expensive target," Dragov stated bluntly, his tone unsympathetic.

Michael replaced his glasses and tried to read Dragov's face. It would be no good attempting to appeal to his sympathy or concern for human rights. Dragov's dark eyes were empty of all expression like a sunless sea. This man was unreachable and very dangerous.

"Kathy said you wanted to see all the documents." Michael led the way to a small dining room. "I've laid all the magazines, books, and press clippings out on the table for you," he said, "you can go through them here, it's private and it will save hotel bills." More than ever now that he'd met him, Michal had no intention of sharing his apartment with Dragov---he found the chilling presence of the man unnerving. "I'll move in with my wife---we're cited---until you're finished."

Dragov nodded.

"There's food in the kitchen, make yourself at home."

Dragov turned on the lamp which cast a pool of light over the table, then he pulled up a chair and drew a file towards him. He was not sure exactly what he was looking for, but he knew that amongst the mass of clippings, there would be something about Mischa Barton he could use, some weak spot, perhaps, in the guard system.

Michael had packed a bag and was heading for the door when Dragov stopped him.

"Is there something else about Mischa Barton of which I am unaware?" Dragov inquired, puzzled. "How is it possible for something like Pescadero to exist in a country like the United States?" he continued, his disbelief apparent. "What was the nature of Ms. Barton's offense? And how long has she been an actress?"

"Mischa Barton has been an actress since childhood, with notable appearances in shows like 'Star Trek' and several others throughout the years," Michael began, his tone filled with reverence. "Her lineage is impeccable. Mischa's father is Lord Paul Marsden Barton, the most powerful man in Europe, both politically and financially. But it's her ancestors that truly elevate her status. Did you know she's related to one of the Tudor kings? Henry VII, to be precise.

"The charges against Mischa Barton stemmed from a DUI incident," Michael elaborated, frustration evident in his tone. "Despite her honesty about being under the influence during the incident, the judge's arrogance led to her sentencing at Pescadero. I'd say he probably saw her case as an opportunity to make a name for himself and to flex his authority without considering the human cost.

"Now, about Pescadero....In the United States, the Constitution places strict limits on the power of the federal government. It outlines the rights and freedoms of individuals and imposes checks and balances to prevent any one branch from becoming too powerful. However, when it comes to matters of law and order, each state has a jurisdiction of its own. While the federal government is restrained by the Constitution, states have more leeway to enact laws and regulations of their own. This means that while there are federal laws that protect certain rights, such as those outlined in the Bill of Rights, states can have vastly different legal systems and standards. Some states may have more lenient or stringent laws, depending on the political climate and the values of the population. In the case of Pescadero, it's likely that the laws of California and the decisions of its local judges allowed for such a facility to exist, despite its questionable practices and conditions."

After Michael left, Dragov worked until the early hours of the morning, then dozed on the sofa for a while. He worked again for the rest of the day. When his eyes became too tired to follow the print he stood at the window and looked down at the street.

On the afternoon of the second day, he left the apartment and made his way to a house on the Rue Paul Valery in the fashionable 16th arrondissement just off the Champs Elysees. The house was a brothel, the best in Paris, once owned, the story went, by the famous Madame Lucile. She had received police protection since the Second World War when an integral part of the Resistance Movement was run from her establishment. She had sheltered Jews and Allied airmen alike from the Nazis, and old men handed her phone number on to their sons. Times had changed. Madame Lucile had retired and the new owner, Madame Pauline, had made her reputation and fortune in Moscow as the official whoremonger to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Dragov was shown into the ground floor reception area. There was a small, well-appointed bar and beyond that a hall, lit by chandeliers, with a stairway leading to it from the bedrooms above. It was just after three in the afternoon, the time when French businessmen liked to relax after lunch. Madame Pauline was behind the bar. She was a stocky fifty-year-old woman, expensively dressed, with a round face that showed her age despite her carefully applied makeup. Pretty girls were reporting for work dressed in Levis and jerseys, nodding to Madame Pauline as they passed and then reappearing in chick evening dresses.

Madame realized Dragov was a stranger and poured him a drink. "Cheri," she said, looking him over, "I am glad you have come here. The girls on Rue St. Denis know what you want but I, Madame Pauline, know what you need."

All of the windows of the building were shuttered, closing out the dark gray of the winter afternoon. The lights around the bar were subdued.

"Would it be possible for me to talk with you privately?" Dragov asked.

Madame Pauline thought he was shy and led him to a side room with long curtains and antique chairs. She took twelve or so photographs that showed her girls in poses that were sensual, and erotic, but not vulgar, and tossed them down in front of him with the confidence of a hustler dealing a stacked deck to an unsuspecting player.

Dragov shook his head and gave her back the photographs. "I was in Moscow," he said quietly, "you would have known my uncle then." He gave her the KGB identification code. Madame Pauline's eyes narrowed as she sensed trouble. "What was your name again?" she asked.

"Dragov. Viktor Dragov."

The name rang alarm bells in her mind and instinctively she moved away from them. She had left the U.S.S.R. behind her; she wanted no part of it here.

"You can tell me where Zoltan is," Dragov said. "I need to find him. I have information that he's working with you again. He's nearby, I know that."

"Who told you about me?" Madame Pauline asked softly.

"It doesn't matter. Where's Zoltan?"

"There will be trouble," Madame Pauline warned.

"No," Dragov said, "there will be no trouble. I can handle Zoltan."

She looked into his face and believed him. She knew all about Dragov's training as a KGB assassin, about his defection to the West. "The building opposite this one," Madame Pauline said quickly, "the third floor in the front." She got up. "Now please leave here."

Dragov walked across the street. The building was let as apartments and there was a sign up announcing that it was shortly to be demolished to make room for the new Peruvian Embassy. He opened the door and crossed the stone-flagged hallway. A creaking, old-fashioned lift took him up to the 3rd floor. He stood on the landing, allowing his eyes to grow accustomed to the gloomy rays of light that penetrated from one dirty window. There were 3 doors off the landing. Dragov chose the one that opened into the street-facing apartment. It wasn't locked. He quietly let himself in. The occupants had moved out already: the hall was dark, light fittings wretched out, and strips of paper torn from the walls.

Dragov stepped over some cardboard boxes and a cracked lavatory cistern. From one side he heard the noise of a tap dripping into the bath. He went down the passage. The shutters across the window of the front room had been closed and only the barest glimmer of light filtered into the apartment. Dragov walked softly, but even so, his footsteps creaked on the old boards. He checked the bedrooms, the handleless doors swinging open at his touch. Then he came back along the passage and stood in the doorway of the living room. He knew Zoltan had to be there, and he waited.

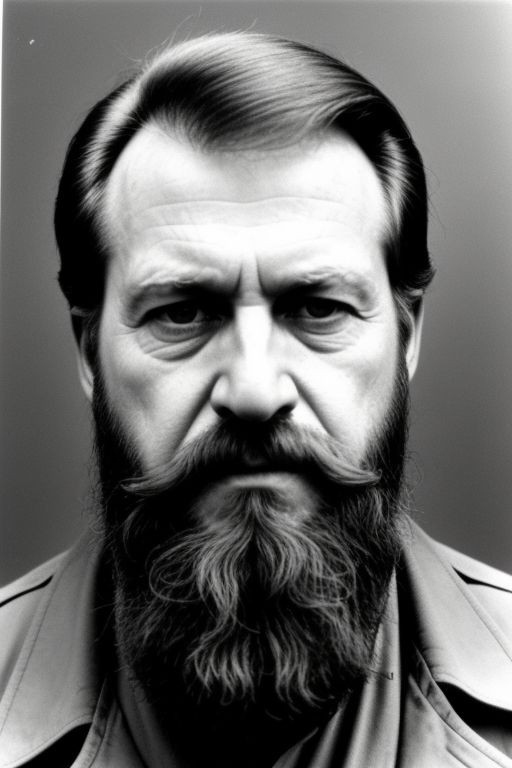

A low chuckle came from the darkness of one corner, a movement which was the clicking of a flint, and then the gas flame of a lighter flared. A weathered face appeared, stern and bearing the marks of a life spent in the shadows of espionage. The man's sharp features were framed by a closely cropped beard, adding to his intimidating presence. His piercing eyes held a depth of experience and a hint of danger, reflecting the many challenges he faced in his career as a covert operative. Despite the severity of his appearance, there was a calculating intelligence behind his gaze, always assessing and analyzing his surroundings with precision.

"Viktor, my comrade," Zoltan said and there was almost a childish pride in his voice, "you didn't get past me. I saw you long ago in the street, you could have been dead any time." Dragov ignored the Dragunov rifle and walked into the room. Zoltan let him come. He was seated by a tall window; there was no glass in the pane. He pulled the metal lever beside him and the shutter opened an inch or two, letting some light into the room. There was a sleeping bag rolled out on a piece of cloth, a folded blanket in front of the window where he could rest his arms, a tiny campus gas stove on which he could heat his food, and a bucket in which he could defecate. He had been in that room for days, and the place reeked of urine and damp and unwashed bodies.

"How long have you been here?" Dragov asked.

Zoltan glanced up at the wall where he had scratched the days. "Eleven. He will come in the next three or four days. I can feel him coming, just like the old days," he said. "Remember, I would wait and wait and sure enough my target would walk into my sights. You can get anybody if you wait long enough."

He reached into his pocket, shook out two pills, and swallowed them dry.

"You take many of those things?"

"Sure," Zoltan replied. "When I'm high I can look down to the street at night and pick out a face with my naked eye, just like I'm looking at it through a starlight scope.

He rolled onto his stomach, cradled his rifle, and quickly checked the street.

"Who are you waiting for?" Dragov asked.

"Jack Avery, he has a girlfriend at Madame Pauline's. Whenever he comes to Paris he goes to see her. Do you remember our friend from London?" Dragov recalled Avery, the solitary scourge of Europe and the U.S.S.R., who trafficked heroin and cocaine like a phantom in the darkness. The KGB had attempted to apprehend him previously, but he was too elusive and astute.

"Which of our esteemed gentlemen is footing the bill this time?" Dragov inquired.

"I don't know," Zoltan said. "I don't care. I just take the money and kill whoever I'm paid to kill."

Zoltan was born in Moscow, Russia, in 1945, just after the end of World War II. Growing up in the tumultuous aftermath of the war, he witnessed the rise of the Soviet Union and the intense ideological struggle of the Cold War era. Inspired by the patriotic fervor instilled by the government, Zoltan joined the KGB at a young age, eager to serve his country and defend its interests against perceived Western threats. His most significant mission came during the height of the Cold War when he was tasked with infiltrating and dismantling a CIA-backed espionage network operating in Eastern Europe. Zoltan's skill and cunning allowed him to successfully neutralize the threat, earning him accolades within the KGB. However, disillusioned by the corruption and political intrigue within the organization, Zoltan eventually grew disillusioned with the Soviet regime. In 1971, he left the KGB and relocated to France, where he began working as an independent assassin, leveraging his extensive training and experience to become a highly sought-after operative in the shadowy world of international espionage and clandestine operations.

He would choose his targets, hole up, and wait for them to walk into his sights. With the heavy Dragunov he used, he could pick off a man at nine hundred meters. The pills he took by the handful kept him on a constant high. "I can't make it as anything but an assassin," he said.....

"You want some coffee?" Zoltan asked.

Dragov shook his head.

"I need someone to protect me," he said. "I've got a contract, but I need someone to keep the KGB off my back."

"Why me?"

"You are the best I know."

"It's true," Zoltan turned back to the street. "You know," he went on, mostly to himself, "I don't care too much how I kill. Sometimes I just lie here sticking this rifle out of the window leading on people and cars as they pass by and the rest of me is a dead man, the only feeling I have is in the tip of this finger." He held up his trigger finger and smiled.

"Tell me where I can find you," he said. "I'll be along in a little while."568Please respect copyright.PENANAqEbb9C5uIy

568Please respect copyright.PENANA6Yh3bacGlL

568Please respect copyright.PENANAjo5yVDqFnj

568Please respect copyright.PENANA39QE6fSh41

568Please respect copyright.PENANA40pXcSQFxm

568Please respect copyright.PENANAZfO6meVeIe

Kathy Lakas made her way through the crowded Los Angeles streets to the Getty Center. She had made an appointment with one of the directors and she was ushered into his office.

"Ah, Miss Lakas," Dave Thompson greeted her from behind his desk. He was a distinguished-looking man in his late fifties with silver hair swept back off his forehead. "You have come to see the altar candlestick." He reached through his keys and led Kathy through the museum to the section housing their collection of Chinese ceramics.

They stopped before an armor-plated glass wall. The altar candlestick was spotlighted on the shelf behind, in pride of place in the collection. The label described it as early Ming c. 1400-1450, perfectly potted and beautifully decorated in underglaze blue.

"Magnificient, isn't it," the director commented over her shoulder, "and of course so very rare. As you know, the only other one like it is in the Peking Museum. Your father was a very fortunate man to have owned this."

"He brought it out of China with him in '46," Kathy said. "It was the only possession he could salvage after half a lifetime's work and four years in a Japanese P.O.W. camp. At that time not even he knew how rare it was."

"Would you like me to open the glass?" the director offered. To hold such a rare ceramic was an honor he reserved only for the very privileged. Kathy shook her head.

"I've come to ask you for a valuation. How much could we expect if my brother and I decide to sell it?"

The smile left the director's face. "Since your father left it with us, we have always felt that it was meant to be part of our collection."

"No," Kathy said firmly. "His will was quite clear. The altar candlestick was left to my brother, Michael, and me."

"I think we'd better discuss this in my office," the director said. He turned abruptly on his heel and left Kathy to follow him. By the time he reached his desk, Thompson had been able to recover some of his composure. "Well now, Miss Lakas," he said, "I suppose technically the candlestick does belong to you, but if you took it away from us, it would leave an unfillable gap in our collection. I'm sure your father wouldn't have wanted that," he said shrewdly, but he missed his mark with Kathy.

She fixed him with a very direct gaze. "You still haven't told me how much the candlestick is worth," she prompted.

"A piece as rare as this is priceless," Thompson shrugged resignedly. "The only way to put a price tag on it is to hold it up for auction and then of course there's the risk of it passing into a private collection."

"I don't want your museum to lose it," Kathy told him, "but my brother and I may need to raise three hundred thousand dollars. Would you pay that much for it?"

Thompson knew that the price she was asking was more than fair. "I'd have to put it to my trustees," he said. "How urgently do you need an answer."

"I'm leaving L.A. at the end of the week. Could you let me know by then?"

Before she left the museum, Kathy stopped again for a last look at the candlestick. Its value to her and Michael lay in that it had always represented an important link with their father. She felt guilty at the thought of selling it but consoled herself with the memory of her father telling her as a child that no one person should be able to own such an ancient and exquisite piece. Kathy's father was a man who shared the same idealistic beliefs as his daughter and was sure that he would approve the use the money would be put to.

ns 15.158.61.16da2