x

x

Dimitri awaited Alexei's return from the camp gate in his tent, seated behind his field desk and scowling at the aimless patterns he had been scratching on a pad of paper before him. He knew it'd been a mistake to greet Alexei in such peremptory fashion. They were brothers, after all, and they hadn't seen each other for several years. A little more warmth might have been displayed without serious prejudice to discipline. His reaction, now that he considered it, had been a little more priggish than needed.

Bringing the noblewoman to a military post was technically a breach of the regulations, but it could've been handled a little more delicately. Dimitri could have suggested the lady's removal after an exchange of formalities that were recompense for any amount of hostility.

What rankled deeper than an affront to the enforced decorum of a military camp, Dimitri realized, was this new demonstration of the fact that Alexei had only a perfunctory interest in Raisa Milekhina, now that he had taken her away from Dimitri.

How else could his theatrical entrance with the countess be construed? Not content with having taken Raisa away from him, Dimitri had to show how little the triumph meant by flaunting a casual affair with another woman. A woman with the countess's opulent beauty and operatic charm was hardly the kid to take a maternal interest in a young officer serving in a new territory.

Somehow, Dimitri realized, he would have to school himself to deal impersonally with his brother. He would have to remember that Alexei's self-absorption was so complete, so perfect, that it was immune to the ordinary methods of reasoning. In a sense, one had to communicate with Alexei through sign language, not because he was stupid but because he lived in a different world, a world with a population of one, himself. Since childhood, Alexei had refused to recognize anyone else's rules and went along with them, if need be, only so long as it took to find a way to circumvent them. His only advantage in dealing with this brother was the fact that Alexei had never been able to fool him for very long.

He looked up from the desk at the sound of approaching footsteps. Alexei marched into the tent, his face rigid and impersonal with military propriety. He presented, in fact, a caricature of the proper subordinate as he saluted and presented his orders.

"At ease," Dimitri said. "Sit down, Alex. Take that camp stood over there."

"Thank you, sir...."

"You can dispense with the 'sir' for the time being."

Alexei managed to lounge gracefully even on so shaky a perch as a canvas stool. "I thought you were going to have me confined to quarters," he said with the boyish grin that had so many admirers.

"That was a silly stunt bringing the Countess What's-her-name into camp. Not that it didn't provide amusement for the men."

"The lady offered to drive me out here, and it would have seemed boorish to refuse."

"The lady, no matter how gracious, would be classified as an enemy national, unless they've recently said they're willing to acknowledge the Czar as their sovereign. We have to be careful out here, Alex. We're on probation in a sense, and a lot of people are waiting for us to make a serious slip."

"May I speak as Alex to Dimitri?"

"Of course. That's why I told you to take a seat. For the moment there's no rank between us."

"I think you're being a little stuffy.

"That's what you've always thought, Alex, but there's nothing I can do about that, is there?"

"You might try not to take everything so seriously."

Dimitri studied his younger brother, once more wondering how it came that his air of irresponsibility, his sophomoric tendency to be flippant on all occasions---a tendency which Alex always exaggerated for Dimitri's benefit----had failed to hamper his career. Maybe it was because people were willing to forgive a touch of the juvenile about a soldier. Soldering isn't a "serious" profession, in many people's views; it's a mere extension of schoolboy play. So long as a soldier impresses everyone with his bravery, people are willing to entrust the lives of their sons and the ultimate destiny of their country to a man whose sense of responsibility is no greater than a wayward boy's. How else could one explain a Napoleon? Dimitri could only hope that some kind of shock---perhaps a closer acquaintance with the true and terrible facts of soldiering in the field---would bring Alex to his senses and keep him from becoming one of those mock heroes, glory drunkards, who dealt out ruin with a grisly high humor and who were truly understood only by the men serving under them.

Perhaps, though, he had always been too fast to judge Alex, perhaps there was more envy, deep in his system, than he dared to admit to himself.

Between the two brothers (physically) there was a strong resemblance, which diminished the closer one came to them. Both were dark-eyed and -complected, compactly built, with something Mongollike about the vigor and ease of their movements. On closer inspection, it was evident that Alexei was a more refined and graceful version of his older brother. There was a stubborn strength, a rocklike quality to Dimitri; he moved squarely on an objective and gave the impression of disdaining subtly and finesse. Alex was quick and fluid in his movements. If Dimitri was a boulder, Alex was a drop of quicksilver. Alexei had a quick and impatient mind and was a creature of intuition, not logic. Nothing could have bored him more than a game of chess or irritated him more than the suggestion that war greatly resembled that game. Alexei could see war only as a matter of individual valor and was outraged by abstract thoughts concerning it.

Some mutation, disregarding the common clay from which their faces had been molded, made Alexei startlingly handsome. Dimitri's face was strong-boned, with high cheekbones, a spare but prominent nose, a firm mouth, and a craggy jaw. His hair was coarse, thick, and straight, black as pitch. Yet there was nothing brutal in the strength of Dimitri's face---it was the strength of simplicity and directness.

Alexei's face looked as if some more classic sculptor had smoothed down its planes and informed them with, not exactly delicacy, but a fineness and mobility, lacking in Dimitri's. Dimitri may have looked at a distance like some displaced Viking chief, but Dimitri was a young Mongol emperor---or so a rather romantic colonel's wife had remarked on seeing them together during Dimitri's visit to St. Petersburg some years before. There was a liquid fire in Alexei's eyes, a challenge that most men and many women responded to with a giddy yearning. Alexei did not bother to hide recognition that in appearance alone he was accorded superiority over other men. An inch or two shorter than Dimitri, he held himself so casually erect that people thought he was the taller of the two.

Born in the right period---so Dimitri dourly remarked to himself----Alexei would have made a splendid buck of the Regency....and with just the right temperament for the role.

But he said out loud: "There are many times when I wish I could take things less seriously, but I don't have your talent for frivolity."

Alexei exposed his very white teeth in a pleased smile. "I'm glad you recognize it as a talent, not a weakness. It takes some study and considerable practice to manufacture nonsense---I mean deliberately, not accidentally. I don't suppose we'll ever really understand one another, Dimitri, but I'm not quite so much of a lightweight as you make me out. If I seem somewhat frivolous at times, you might be charitable enough to look for a reason behind it. Life can rub me raw, too, you know. Maybe I'm only whistling in the dark." Dimitri could see that this was spoken in the spirit of mockery, with a crooked smile of self-deprecation which he particularly detested. "Maybe I, too, am haunted by despair in the final watches of the night."

"I hope you're not turning into a philosopher," Dimitri said. "I like you better as the laughing cavalier." He added, "Well, I suppose it's time I asked how things are at home."

"Yes, please do."

"Come to think of it, I probably know as much as you, thanks to the efficiency of the Imperial postal service. Mother and Father are well. So's Raisa. And you and General Gorshkov, according to Father, are impatient to wade into the carnage."

"I guess you're up to date. The last letter I had was just before we took the last train from Sebastopol."

"When are you and Raisa going to get married?" Dimitri blurted out. He hadn't had any intention of asking such a question and regretted it the moment it was uttered.

"I wondered when we'd get around to Raisa. Still smitten?"

"I'm fond of her, still, and hope she is still fond of me."

"Fond. Now there's a mealymouthed word. I've never been fond of anyone, especially a female, in my life."

"You always did run to extremes."

"Furthermore, Dimitri, I don't believe you're fond of her either. I think your feelings are a hell of a lot stronger than that. Remember your last leave? Most of it spent in St. Petersburg mooning around Raisa?"

"I don't believe I was mooning around her, but I remember she was distressed at the time over your conduct. You were carrying on quite openly with the wife of an assistant military attache in one of the embassies."

"And you lent her your big-brotherly shoulder to cry on. There was, I understand, a dramatic scene in the Gorshkov garden, an exchange of protestations between you and Raisa, which may have been sincere enough on your part but were of dubious value on Raisa's. She loves scenes, you know, like most women, and mustn't be taken too seriously."

"I didn't take it too seriously myself."

"Maybe not. I hope you're not a complete damn fool.....Anyway, I wormed it all out of her when I noticed a certain smugness in her attitude after you left St. Petersburg. You know how women are, they like to keep two strings to their bow. All of them, the best of them. I guessed she had an eye on another man; not seriously, because she's not bold enough for an affair with someone else, but someone from whom she could draw comfort. I honestly didn't think it'd be you, after the way she gave you the mitten."

There was a tase of betrayal, a bitter and corrosive flavor indeed, in Dimitri's mouth. It was bad enough that Raisa had drawn those "protestations" from him as a balm to her pride, which he later recognized for what they were, a flare-up of the old passion on his part and a rather foolish and meaningless attempt on her part to get back at Alexei and his casual romances. but it was worse of her to have told Alexei about them, downright dishonorable, except that no realist expected a woman to have a sense of honor.

"Let's forget about it," Dimitri said wearily. "It didn't mean anything to either of us. An embrace or a kiss or two."

"You're sure you didn't tumble her into the shrubbery?"

"Now, goddamn it, Alex...."

"Don't be so fusty, Captain, sir. That's what I would have done in your place. In fact, right after she made her little confession, I had her right on the Persian rug in her father's parlor. Lucky the old general didn't wander downstairs in search of a cigar at that moment."

"I think you'd better get the hell out of here," Dimitri said. The picture that Alexei summoned up for him with a deliberate and relishing crudity made him feel sick with rage and disgust....disgust for all three of them.

"Ah, don't be so namby-pamby. There shouldn't be any secrets between brothers, should there?"

"Why couldn't you have kept it to yourself? How can you speak that way about the girl you're supposed to marry?"

"Because I'm a shameless bastard, and you better get used to that. All the same---even though I can't manage virginal blushes over what passes between Raisa and me---I mean to marry the lady. Make no mistake about that. Don't get up any hopes that you can cut me out."

"I've never had any hopes from the moment you decided to step between us."

"Maybe I would not have been so indelicate if you hadn't turned the countess out of camp in such a lofty manner---like two-bit army whore."

Dimitri felt that if his brother stayed in the tent another minute he'd be unable to control the urge to smash him in the face.

"All right," Dimitri said evenly, "I've had enough of this. Henceforth our relations will be strictly military. You're dismissed, Captain Karamazov."

Alexei quickly rose to his feet, saluted, was about to stalk out of the tent.

Dimitri detained him for a moment. "Oh, there's one more thing....what was the official business that kept you in Korosun?"

"My second-in-command must have understood me. I told him to say I was detained on unofficial business. The Countess was supplying me with information on the customs of the country---and what delightful customs they are. Have I the captain's permission to withdraw?"

"Get out," Dimitri said.

Shortly after noon of an April day a river fleet was assembled on the river near Morkhai to carry the provisional brigade on its expedition into the heart of the oblast of Kenzank. The prime objective was the city of Ikaphoghar in the southeastern quadrant of the Kenzankian desert, the sea of sand dunes shaped like a hand with three fingers. Ikaphoghar, located on the "shore" of the third finger of that hand, was the principal market of the richest oblast in Turania. Its capture would "hit the rebels right in the breadbasket," and sever their communications between the forces in northern and southern Kenzank, as Colonel Spravtsev had pointed out at a meeting of the regiment's senior officers.

The expedition had its risky aspects. It would land some sixty miles deep into enemy territory and its only communications would be across Kenzank and down the Ilburz to the main body of the Russian forces. None of the provisional brigades had been trained in river-borne operations. The flotilla would be manned by soldiers with little or no experience in handling such tricky craft as would carry the expedition to Ikaphoghar. There were reports, too, that the rebels had placed batteries along the southern banks of the Ilburz in anticipation of a Russian move in that direction.

Discussing the reports of possible enemy artillery action as they watched the leading elements of the brigade boarding the riverboats, Spravtsev told Dimitri, "The trouble is, with our lack of navigational skill, we're going to have to creep around the river close to the shoreline. Otherwise, we'd get lost and scattered for sure. That'll bring us close to the guns they're said to have emplaced. The Sasanfanifis are supposed to have a number of Krupp guns, eight-centimeter pieces, and somebody who knows how to fire them in a battery. It's pretty hard to keep an artillery shoot a secret, and we've had word that they've been getting in a lot of practice."

"I doubt whether Turanians would know which end of an artillery piece to aim," Dimitri said. "I'm not downrating them, but according to the reports I've read, they're not even trained in musketry."

"Maybe so, but they've got someone teaching them which end of a cannon is which. I hear that it's a renegade Englishman, a deserter from the Indian Army, who's been instructing them."

"Our gunboats should be able to handle them."

"Apparently you don't know much about water-borne warfare, Karamazov. There's nothing that any kind of warship hates than the idea of dueling with shoreline batteries. They're sitting ducks, while the artillery onshore is dug in and often hidden by the terrain."

"We should be well past that stretch of the riverbank east of the Ilburz's mouth before daybreak."

"Yes," Spravtsev admitted, "there's that consolation---if all goes smoothly and we shove off in time. But it would be plain murder if our wooden boats were taken under fire from the land. You'd best pass the word through your companies that there's to be no smoking and no loud talking on deck prior to our making landfall."

The boarding of the river fleet proceeded smoothly enough that afternoon, with close to fifteen hundred men, carrying just rations and ammunition in their packs, jamming their way into the boats. All animals, whether transport or tentage, were left behind The fleet consisted of seventeen dhows, two chaikas, eight launches, and three riverine ironclads, the Klenovy List, Alaya Ledi, and Kachaniye.

The two companies of Dimitri's battalion were loaded onto six dhows. Two launches towed three of the river barges apiece. Dimitri boarded one of the chaikas carrying the company of Arkhangelsk Volunteers, while Alexei took charge of his company in the other string of three dhows.

Since the conversation in his tent the evening of Alexei's arrival, Dimitri had found nothing to complain of in his brother's conduct of company affairs. Alexei was strict about camp sanitation, stern about drills, concerned over the mess facilities, efficient with morning reports and other forms of paper juggling. He'd kept his distance and approached Dimitri only in the line of duty. Perhaps, Dimitri thought, this was the only way to handle Alexei, keep him at arm's length, deal with him impersonally, coolly, and justly.

And yet.....Dimitri was a little concerned over Alexei's casual acceptance of the situation. It wasn't like him to desist, withdraw into a shell of formality when he felt that he had the upper hand over somebody. There must have been some motive for Alexei's unduly frank discussion of his relations with Raisa Milekhina; it must have been more purposeful than a petulant reply to Dimitri's curtness in ordering the removal of his lady friend. So far as Dimitri knew, though, Alexei had not left the camp long enough to visit her.

But there were other things to worry about now. Water and other supplies had to be hurried aboard and the chaikas prepared to shove off by 4 P.M. to take advantage of the few hours of daylight left. The flotilla must navigate the narrow channel of the Ilburz between Morkhai and the first dunes of the Kenzankian Desert, before darkness could finish the job.

The flotilla finally weighed anchor, led by the little ironclads. The launches towed the chaikas and dhows upriver in a long slow procession over the yellowish-brown water. Thickets grew close to the river and became more menacing with each lengthening of the evening shadows. It was not hard to imagine hundreds of balaratis hidden in the thickets and waiting to spring into the boats when darkness fell. The last purplish blaze of sunset made a garish avenue of the river.

Once the final light had faded, the fleet began having its troubles.

No experienced boatmen had been available and the boats kept running aground in the soft mudbanks and shifting shoals. They proceeded so slowly that it was not hard to get them afloat again, but with each halt, all the chaikas and dhows behind were delayed while the launches maneuvered to free the boats they were towing.

The plan of operations called for the flotilla to reach a medium-sized lake (the maps called it Lake Rahar) by nightfall, but it was well after midnight before the first boats entered the tame waters of the glassy lake. The moon glided a path across the dark waters as the ironclads felt their way along the shoreline and guided the launches and unwieldy craft they towed towards the western reaches of the lake.

30 miles of water were still to be negotiated before they hove to the beach west of Ikapoghar and made their landfall. Disembarkation was scheduled for dawn, but it would be more like noon at the rate the fleet was traveling now.

Dimitri saw that Alexei's launch and dhows were following close behind. His brother had chosen to ride in the launch, although most of the company commanders embarked in the leading dhows with their men. Well, that was a small matter of free choice at that. Maybe he felt in firmer command riding the launch.

Once around 3:00 in the morning an alarm shot through the flotilla when a rocket suddenly soared into the sky from the desert shore to the starboard. Officers and men alike wondered if it was a signal from a Sasanfanif post watching movements on the lake. An ironclad darted in towards the shore to guard that flank, or at least give assurance to the column of boats it was shepherding that an ironclad spiked with three-inch guns was there to engage anything that attacked. If the rocket was a signal as Dimitri suspected, nothing immediately transpired to indicate that the Sasanfanif were ready or able to take action in that dark region. The men sprawled out on the decks of the boats and tried to get in a little sleep before the sun rose and the heat became unbearable instead of just exasperating.

The sky to the west was turning gray-indigo when a headlamp, which thrusts its way into Lake Rahar like some humpbacked monster slipping into the sea, loomed before the flotilla.

As the boats swerved to port to navigate the headland another rocket tore into the sky and popped with a great sheet of white light over the flotilla. It was followed in rapid succession by half a dozen other rockets, flaming alternately white and red. Again one of the ironclads darted to the shoreward flank of the waddling flotilla.

When the lights had died out and left the sky dark again, Dimitri had taken out his map, unfolded it, and turned the narrow beam of a bull's-eye lantern on it. According to Dimitri's reckoning, they had just passed a little lakeside village called Yamin-or-Baru, which was a faint flickering of light to starboard. They still had almost 20 miles to cover before reaching the lakeshore west of Ikapoghar.

Then another series of rockets blazed up from the black mass of the headland.

Sergeant Zykov wriggled his way forward to a place before Dimitri in the bow of the craft. His musket, as always, was clutched in his hand. Awake or asleep, Zykov kept the weapon within a few inches of his right hand. Dimitri suspected that he slept with it under a pillow.

"Any minute now," Zykov said in a low voice, "I figure they'll let us have it. Just about the time we round that hunk of land, I reckon."

"It would be the logical place for them to set up their guns," Dimitri said. He felt oddly comforted by Zykov's presence, the glimpse of his rough, knobby face in the gray light. Outside the army, he'd be a bum, a troublemaker, probably a jailbird; inside the army's protective and unusually forgiving clasp he had a secure place until pension time and the ultimate sanctuary of the Old Soldier's Home if he lived that long.

One of the ironclads began sending a message on its blinker to the launches. That was the first time any kind of light had been shown, deliberately, on any of the boats. With all those rockets lighting up the sky, they likely figured it didn't make any difference. The launches, evidently in obedience to the message they got, began spacing out, making a less concentrated target for any fire from the shore.

By the time the launch towing Dimitri's shows started to skirt the headland there was a faint light from the east and the whole flotilla would soon be visible.

Dimitri took his field glasses from the case slung around his shoulder and raised them to the southern horizon, studying the barren coast and the high ground which crowned the headland.

Suddenly there was a series of flashes, all the more brilliant for the darkness of the background, followed a few seconds later by the thunderclaps of sound that drummed across the filthy riverwaters. It was a shore battery opening up on the flotilla. Judging by the quick sequence of flashes, the guns were being fired by adequately trained artillerymen.

The first barrage dropped far to the left. After a brief interval for adjusting the range, the guns fired a second round. This time they were short. The third would likely drop in fairly close, the target having been bracketed. Dimitri ducked behind the gunwale, although he felt a little silly depending on that frail barrier to protect him from a shellburst. Those guns were big enough to blow a dhow right out of the water if they registered a direct hit. Dimitri tried to close his mind against the image of torn bodies littering the still waters of Lake Rahar.

A few seconds later a shell exploded on the water 100 yards inshore from the dhow, sending up a lukewarm geyser that showered water on the men cowering on the belly of the craft.

The shelling continued. Dimitri lost count of the rounds fired by the guns on the lakeshore.

One of the shells landed close enough to the launch towering Dimitri's dhow to rip open her seams and gut her steam engine. The three dhows, as well as the launch, were dead in the water. Another round from the lakeshore battery and Captain Rollan Karnaukhov of the Arkhangelsk company was laid open by a shell splinter, blood pouring from the gash in his chest. Karnaukhov was a bulky but active fellow, a lawyer in civilian life, who had mistrusted Dimitri as one of those elitist military snobs and had been watchful for any injustice committed towards him or his men as Volunteers. No doubt Karnaukhov would have made the legalistic most of any misstep. But Dimitri had slowly and painstakingly won his confidence, proved to him that military professionalism was quite as ethical as any other. With a deathly pallor, only half-conscious, Captain Karnaukhov submitted to Dimitri's fast and fairly expert attempt at dressing the wound.

There was nothing for the foundering launch to do, now, but cut the towline and let the sailless and powerless dhows drift while her crew labored to keep the steam-driven vessel afloat.

Alexei came along in the launch behind them and shouted an offer to take the men aboard his dhows before they were all sent to the lake bottom.

Dimitri cupped his hands in the shape of a megaphone and shouted back, "Clear out of here and close up behind the others."

Alexei's launch kept chugging slowly alongside.

"Clear out!" Dimitri shouted again. "You couldn't take us into your boats without swamping them."

Alexei still did not give the order for his launch to proceed at full speed.

"That's an order! Clear out!" Dimitri called to him.

Alexei finally complied, having sighted one of the squat little gunboats, the Kachaniye, pouring on the coal and coming to their rescue. The gunboat, her crews still firing away at the onshore battery, managed to take the launch's crew aboard her and picked up the dhows' towline.

Within a few minutes, they were out of range of the Sasanfanif guns. Only the Arkhangelsks' captain had been wounded on Dimitri's boats and the bleeding from his wound seemed to have been stanched. One of the regimental surgeons aboard the gunboats would probably be able to patch him up without serious consequences.

"Have you any idea how lucky we are to be out of that mess?" Douglas muttered to Sergeant Zykov.

"I thought we were going to be skeletons in the river mud, sir," Zykov said with unwelcome candor.

It was midmorning by the time the expeditionary force stood off the riverbank west of Ikaphoghar. Not a shot was fired from shore as the launches began towing their craft as close to the land as possible. The flat-bottomed chaikas were admirable for this purpose. Ikaphoghar was only two miles away and this riverbank obviously should have been defended as the only feasible seaward approach to the city. The rebels, apparently, were adopting the Asian tactics of defending themselves only from within their walled cities; soon enough, no doubt, they'd seize upon the practicability of striking from ambush from cliffs and canyons.

Dimitri and his battalion breasted their way through the dirty water from their boats to the muddy bank of the river. They sorted themselves out in company formations, stood at ease, and looked about them with tourists' eyes at the lines of date palms nodding featherly in the insubstantial breeze from Lake Rahar, the forbidding desert behind the riverbank, and the wagon road straggling along the edge of the desert towards IIkaphoghar.

General Gorshkov, the commander of the provisional brigade, and his regimental commanders were holding a quiet and undramatic conference off to the left, the general puffing on a cigar and listening to the suggestions of a staff officer. Without the uniforms, they would have appeared to be a group of sportsmen on an outing, discussing the prospects of the hunt.

Offshore, the gunboats idled, the black snouts of their 3-inchers pointing inland and their boilers working up steam for the dash up the riverbank, once the landings were completed, to cover the brigade's assault on the city from the left flank. The chaikas were being used to lighter in several pieces of the light artillery which had been lashed to the decks of the gunboats.

When the conference adjourned, Colonel Spravtsev came over to Dimitri, his thigh-length, old-fashioned cavalry boots kicking up a little sandstorm in the haste of his approach. It seemed likely to Dimitri that his battalion had been given the honor of leading the assault. Senior officers rarely hurried in your direction unless it was news of that kind.

"You're going in first," Spravtsev told Dimitri. "Take your outfit up the road and hit the town from the west. The rest of the brigade will come up behind you and form a line of battle to your right. The first scouts have returned, and there's no line of resistance between here and the city. But watch out for a surprise attack from ambush along the way."

"Any idea how many people they've got defending the place?" Dimitri asked. He tried to visualize the desert city with its rotting walls, reeking bazaars, mosque, khan's palace, and the sprawling brick slums surrounding them. Is there any fieldwork outside the city?"

"No fieldwork," Colonel Spravtsev said. "But they've got a line of riflemen placed behind a kind of low wall on the west side of the town. You'll have to make your crossing under fire to get at that wall or somehow manage to storm the bridge. The brigade is barricaded, so there's a good chance you'll get a bloody nose whichever way you decide to go."

"General Gorshkov's orders are that you're to push into the town if you can do so without taking heavy casualties. Otherwise, you're to pin down the enemy in their positions and wait for the rest of the brigade to come up on your right. No rashness now, Karamazov. It's not worth it. We can invest in the town and take it at our leisure, if necessary, but we'd like to take a sizable bag of prisoners if the price isn't too high."

"What about support from the artillery?"

"My God, Karamazov, how much do you want from a simple little operation like this, going up against undersized fellows who can't short worth a damn?"

Dimitri noticed that Alexei had moved close enough to overhear his exchange with Colonel Spravtsev and that he was smiling unpleasantly. Somehow that near smirk bothered him more than Spravtsev's undiplomatic way of expressing himself. Both he and Spravtsev knew that the colonel wasn't suggesting that Dimitri was being overcautious, but Alexei obviously thought he was being rebuked.

"Anyway," Spravtsev continued, "they haven't unloaded the guns yet. Make tracks for Ikaphoghar, Karamazov, and good luck."

The battalion swung out onto the road towards the city, deeply rutted by the lumbering befegaru carts which were the principal means of transportation in this oblast. It was only noon when the column rounded a bend in the road and caught sight of the roofs of the city they were about to attack. The battalion came within several hundred yards of the fortified bridge whose watchtowers commanded the western approach. At least a hundred rebels, Dimitri observed through his field glasses, were placed in the bridge defenses and behind the barricade, and others could be seen popping their heads over the low wall covering the river crossings to the right. He gave orders for his companies to form a skirmish line.

Douglas summoned Alexei for a fast consultation behind a clump of scrub growth. "I'll take the Arkhangelsk company and demonstrate to the right of the bridge," he said. "You make a rush for the bridge itself, and if you can take it with the first assault---fine. Otherwise, pull back."

"And then what?'

"Wait for further orders."

"I hope you don't intend to stall until the artillery comes up and blows that bridge away for you. We'd lose one hell of an opportunity."

Dimitri studied his brother briefly. Alexei's face was tense with excitement, alive with the prospect of whatever it was he looked forward to on the other side of the battle. Glory was one word for it, somewhat tarnished from excessive use. Himself, he reflected momentarily, for himself there was only a tearing emptiness inside. Maybe it was fear---partly it was, certainly---and definitely, it was the dread anticipation of the ugliness ahead. Once you were "blooded," according to theory, you were callous to the ugliness of armed conflict. Dimitri doubted it would ever be anything but sickening to him; he could never be a veteran in the sense of indifferent acceptance of death and suffering. His strongest and vainest hope was that the next hour would somehow be telescoped in time and that it would be a fast blur---no matter what the outcome. Alexei, however, was living more intensely, soaking up the tension and uncertainty of what lay ahead, than he could enjoy any other moment in his life. Alexei anticipated nothing but the joy of untrammeled action, with no fast forethought of the consequences.

"Just follow orders," Dimitri reiterated, wishing he could say something more forceful. "It's my responsibility."

Alexei had started to rejoin his company when Dimitri said, "Just a minute, Alex." The younger man turned in his tracks, evidently hoping that Dimitri would permit him the discretion of pressing the attack no matter the cost.

"Good luck, Alex," Dimitri said.

"Is that all?"

Dimitri nodded.

Alexei, his face impassive, acknowledged with a half-salute and went on his way.

In a line that was almost 300 yards long, Dimitri's company advanced towards the scrubland bordering the low western wall of Ikaphoghar. Dimitri had passed along orders that the Arkhangelskis were to push as close as possible to the wall without suffering too heavily from rebel gunfire. They were to take cover and keep up a steady fire against the enemy line.

Before giving the signal for the advance to begin, Dimitri looked down his skirmish line with approval. The men had been detached from their father's plow handles not many months ago, but they were calm and steady enough for their first time in combat. The Swedes and Finns, gawky towheads with pale blue eyes, slouching and unmilitary, would never really fit into any uniform but overalls. Their response to him as an officer had been decidedly casual, not rebellious, but not enthusiastic either. Still and all, they looked like men who would do the work of the infantry competently.

Dimitri held out his revolver, aimed skyward, and fired one shot. The Arkhangelskis started, plodding silently forward, as if following invisible furrows, without a single yell. Dimitri was at the left side of the line, with Sergeant Zykov and his musket beside him.

By the time they cleared the rough scrubby meadows and bushes, they were within range of the riflemen behind the wall. A desultory and inaccurate fire greeted them. The range, Dimitri estimated, was about 250 yards and the enemy was equipped with Mausers, but they weren't making their shots count.

Dimitri and his company plunged into a small trench, about thirty feet wide, each man standing shoulder to shoulder. The company climbed out of it without having suffered a single casualty.

To the left, where Alexei's company was launching its assault on the bridge, a much heavier firing broke out.

The Arkhangelskis were just starting up the dusty wall of the trench when a field gun opened fire from the Turanian line, off to the right.

The first shell burst among a small group of stragglers hauling themselves out of the trench in the middle of the skirmish line. Several men simply disintegrated in rags and bits of flesh, others lay in the dust with gaping wounds. One man, Dimitri saw, was all but cut in two. A few strings of tissue were all that held him together, yet for a few horrible seconds his legs thrashed and he screamed and slobbered and begged someone to shoot him. Could the warmongers in Moscow imagine that this was what valor in battle meant? "I don't know whether to vomit or run," Dimitri heard Sergeant Zykov say---and that seemed to be an accurate summation of the rest of the men.

Another shell burst slightly short of the line and tossed up a fountain of mud. The Arkhangelskis blurred into the dusty and sterile earth.

The Turanian gun had them directly in range.

Either they had to retreat to the cover on the other side of the trench or go forward.

Dimitri lay there for a moment, wondering if he could get them on their feet for a run at the wall. The rifle fire wasn't half so dangerous as that single field gun off to the right.

He was slowly rising to his feet when he heard a yell of Viking-Teutonic rage that welled up from every throat in the company. The Arkhangelskis had gone mad. They were jumping out of their burrows, waving their bayoneted Mosin-Nagants, and howling like maniacs.

Before Dimitri could issue an order, they had taken battle out of his hands and gone loping towards the wall. Al that was left for their commander was to follow his men as best he could.

Some of the Turanians, taking one look at the pale-eyed lunatics rushing at them, dropped their guns and fled. Most of them, however, tried to stand their ground, kept firing, and tried to defend themselves when the Arkhangelskis hurled the wall and flailed their way into the Turanians' midst. By the time Dimitri and Sergeant Zykov clambered over the wall, the Arkhangelskis had seized the position and were eager to continue the advance.

Well before nightfall, Ikaphoghar had fallen to the Russian forces and the rebels had fled the town, taking with them most of the population. Dimitri's company had seized fifty to sixty prisoners and herded them into a compound built by a British trading company. The only repulse was suffered by Alexei's company, which took a number of casualties trying to storm the bridge and then retired as Dimitri had ordered. General Gorshkov, Colonel Spravtsev, and other senior officers were unstinting in their praise of Dimitri's "well-timed assault" which broke the Turanian resistance even before the rest of the brigade came up to their right and wheeled into the city in a futile attempt to cut off the defenders' flight.

"I'm afraid, sir, it wasn't timed or planned at all," Dimitri told General Gorshkov. "The success was an accident. I had intended the attack on the wall as a demonstration, to divert attention while my other company attacked the bridge. It was a case of mass insubordination. The men went forward without orders."

"I hardly think we'll throw them into the guardhouse," the general said.

Dimitri established battalion headquarters in the offices of the British compound while the rest of the brigade billeted itself in the buildings around the plaza. Outside the plaza, it was an eerily empty and silent city. Except for a few Mongolian shopkeepers, who were doing a roaring business with the Russian troops, the twelve thousand inhabitants had preferred sharing the rigors of the desert with the rebels to rubbing elbows with the Russians. The propaganda streaming from Rakllama's printing presses obviously was having its effect, even in the hinterland.

Dimitri did not see Alexei until later that evening after Alexei had seen to it that his dead were buried and his wounded were properly cared for. Alexei reported to him at battalion headquarters, a bruise the size and color of an eggplant disfiguring the right side of his face, where he had been butt-stroked by a Turanian rifleman.

Alexei saluted with punctilio and said, "Congratulations, sir, on your magnificent victory this afternoon."

Dimitri shrugged and said, "It wasn't planned that way, as you know. At ease, Alex. Sit down for a moment."

"No, thanks, there's still work to be done---housekeeping chores, mostly. Maybe I'll be more successful at them than the fighting."

"Good Lord, Alex, you're not taking the setback at the bridge personally, are you? It was just too strongly defended. Nobody can blame you for that."

"Hardly a consolation. I lost a dozen men proving it couldn't be taken. I'm wondering why you elected to attack the wall and not the bridge. A shrewd choice, at any rate."

"I'm not going to quarrel with you, Alex."

"As you wish, sir. I'd better get on with my work. Colonel Spravtsev suggested it'd be a good idea if we pried some information out of the prisoners. The general would like to know which way the Turanian forces are headed before he begins pursuit. Incidentally, I understand the battalion is destined to garrison Ikaphoghar while the rest of the brigade hunts down the rebels."

"That's right."

Dimitri had been trying to assess Alexei's attitude, his odd calm, as Alexei spoke of questioning the prisoners. He hesitated over how to caution him against excess without offending him and wished for the ten-thousandth time he had a less touchy subordinate. "Alex...." he began. "Don't be too vigorous about prying information out of these people down in the compound. I think I know something of the Turanian temperament. They're proud and courageous people. You must have noticed that from the way their untrained men held their positions today. A little kindness will go a long way with them, especially since they've been taught to expect brutality and contempt from us."

"Kindness?!" said Alexei with a chilling laugh. "To the enemies of Mother Russia? I think not, dear brother."

"The fight's over. You can't take revenge on unarmed prisoners."

"I am under direct orders from Colonel Spravtsev." Dimitri spun around and walked out without awaiting dismissal."

Dimitri and Sergeant Zykov bedded down on the floor of the office. Dimitri was exhausted, having missed the previous night's sleep, and fell into a dreamless pit of slumber. Sergeant Zykov, whose instincts were more catlike, was awakened shortly after midnight by the sounds of a disturbance below. He looked out the window and saw the prisoners huddled on the ground, the sentries pacing on the walls. Much louder now, a howl of pain and defiance welled up from below, the same sound which woke up the sergeant.

Sergeant Zykov went over and shook Dimitri's shoulder repeatedly until he woke up.

"What is the meaning....."

"Sorry, sir, but there's something going on down there you might want to know about."

A moment later came another of the animallike howls.

Dimitri and the sergeant hurried downstairs, through the compound, and into one of the ground-floor rooms of another building where the sounds seemed to be coming from. It had formerly been used as a storeroom but now was bare of all but a table and some chairs. A cluster of army lanterns swung from one of the rafters in the middle of the room. Until a few hours ago it'd been used as an operating room by the regimental surgeon, and in one corner was a wooden bucket testifying to his handiwork, overflowing with bloodied dressings, bandages, and cotton swabs. A mangled hand that had been amputated halfway to the elbow seemed to be groping its way out of the bucket. The stink of blood and chloroform and disinfectants was almost overpowering.

Now the room was being used for less merciful proceedings. On the table, still bloodstained, was a Turanian with a ridiculously distended belly. He was tied to a table and a funnel had been placed into his mouth.

The other occupants of the room were Alexei, his first sergeant, and two privates.

Just as Dimitri and Sergeant Zykov entered the chamber one of the privates poured dirty river water into the funnel while the Turanian thrashed about and uttered strangled cries.

"What the hell's going on here?" Dimitri demanded. "What are you doing to this man?"

Alexei turned around abruptly, resentful of the interruption. "We're giving this fellow the water cure. He's got a gallon or two in him now. I believe it's time for another question." Alexei leaned over the prisoner and inquired in an impersonal voice, "Now, once again, you scum, where did your people go when they left Ikaphoghar?" The little man on the table, his eyes rolling with terror but still obdurate, shook his head.

"Sergeant!" snapped Alexei.

Alexei's hulking first sergeant stepped forward and suddenly crashed down on the prisoner's painfully swollen belly with his elbows and forearms.

The prisoner screamed and a column of water shot up from his gaping mouth. A paroxysm of heaving and vomiting, followed by a trickle of blood, seized the subject of the interview.

"That's enough!" Dimitri bellowed, trying to keep his voice under control. "All of you men clear out of here at once. You, too, Zykov!"

After the men had filed out, Dimitri faced his brother and said, "Did Colonel Spravtsev order you to torture these people?"

"I was given the job of finding out where the rebels are hiding and, by God, I will, providing no lily-livered son of a bitch interferes with me."

Dimitri shot his fist into Alexei's face and watched him sail backward and collapse into a corner. He stood motionless as Alexei regained his feet. "Come on," Dimitri said. "Make a move at me. It seems that about every five years I have to batter the daylights out of you to teach you manners. Don't you realize it's peculiarly unfitting for one brother to call another a son of a bitch?"

Alexei chose not to attempt retaliation, and slowly buttoned his tunic. Dimitri knew he wasn't afraid to fight it out, because they'd fought on close to equal terms too many times in the past. Alexei, he believed, was hoarding his wrath for some bigger revenge.

"Whose side are you on?" Alexei said. "Your Czar's? Or those raggedy-ass rebels in the desert?"

"I've known Colonel Spravtsev for a number of years, and I know damn well he'd never sanction using force on a prisoner of war."

"They won't talk without encouragement," Alexei said. "And this fellow here is the only one in the compound that speaks Russian. He won't even give his name or where he's from. He spat in my face, the bastard." Alexei fingered the livid bruise on the side of his face. "For all I know, he's the one who smashed me in the face with a rifle butt."

"You'd better get out of here," Dimitri said wearily.

"All right, you serve him tea and ask him kindly to tell you where his friends are. If our columns march into an ambush, because we didn't get the information we need out of him, it'll be your fault, not mine. I'd give the water cure to every one of the little bastards out there in the compound if it would save one of our men's lives. Can you say the same?"

When Alexei had left, Dimitri went over to the table, unbound the prisoner, and helped him to a sitting position.

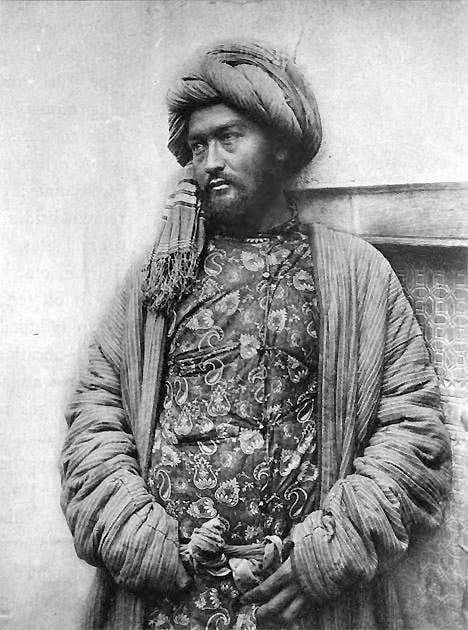

The retching finally came to a halt, and the man raised his head. Dimitri saw that he had a broad forehead and finer features than most of the people of Kenzank he had seen. He dressed differently than most Turanians, too, his turban being green, and his pantaloons striped.

"You speak Russian?" Dimitri said.

"Yes," the man said, enunciating very clearly. "I was educated in Kyiv as well as the great Russian University in St. Petersburg."

"Are you a Turanian? A Shi'ite Muslim?"

The little man spat fiercely. "No. My people are the Seraris. We are of the Sunni sect. Do you know the difference?"

"Yes."

"I am not a Turanian. My people have nothing in common with them."

"Then what were you doing in Ikaphoghar this afternoon?"

"I was not fighting with the rebels, if that's what you mean, although my sympathy for them may grow, particularly after tonight. That officer is your brother?"

Dimitri nodded.

"He resembles you in a way, but then all kufaris look alike to us. The Russians, the Chinese, the Mongols, it makes no difference."

"Did you prefer the Sultan to us?"

"It is not a question of preference, as we have no choice."

"I doubt whether most people would agree with you. At least I hope not. They seem to have a sharp memory of the Sultan's dungeons. The Sultan's prison in Korosun is about the grimmest place I've ever seen."

"Yes, the Sultan was harsh and we hated him. But you Russians are guilty of something just as bad in its way. It is your imperialism. Your smugness and condescension. You have achieved a refinement of the European talent for self-righteousness. We can respect the Mosin-Nagant in your right hand, but the Bible and schoolbook in your left are really intolerable."

"I still don't understand your presence in Ikaphoghar."

"Perhaps you would like to start pouring water into me again." The Sunni smiled boldly. "No, you are a different kind of man, not like your brother. I will speak freely. My name is Fenuldhun. I am what you might call a protege of Hanif Fenun, the Khan of Cteldun. It was he who sent me to the schools in Kyiv and St. Petersburg.

"I was sent to Kenzank to learn what I could of Rakllama's rebellion against the Czar, and what kind of people you Russians really are. I am afraid my contempt is balanced quite evenly between your people and those frightened maggots who ran away from their homes today. They should have died here on their doorsteps, if necessary. I warn you, do not come to Cteldun Oblast expecting so easy a time. We will fight you until there is not a Serari, nor a Russian left. We are a different people than these Turanians."

"Since you were here as an unarmed observer," Dimitri said, "I must apologize for the treatment you have received. If you had told my brother your story, he might have been less...."

"Cruel? I respect him for that. He is a strong and violent man. I believe, however, that a Serari would have conducted such an interrogation with more imagination and refinement. It would have been hard for me to withstand such an examination as my own people could devise."

"You'll have to spend the rest of the night in the compound, Fenuldhun. In the morning I'll take your case up with my superiors and try to arrange transportation for you back to Korosun."

"That is gracious of you," Fenuldhun said. "It does not alter our situation, however. We are enemies. You are the brother of the man who humiliated me. Did you hear my screams? In a Serari, such behavior is contemptible. Perhaps I have been overeducated. Learning, I think, deprives a man of certain primitive virtues. In my anguish, I laid down a curse on your brother. Unless I wish to forfeit my hopes of heaven, I must see to it that he dies as meanly and bitterly as can be arranged by one man for another. Do you understand?"

"Of course." Dimitri couldn't help grinning at the Serari's soft-spoken ferocity. "We Slavs have been known to lay down curses ourselves."305Please respect copyright.PENANAnWMUVlXEFf

"I am glad to hear that, honored sir. Know that this one will cause you no amusement, as it includes not only your brother but all his family."

When Dimitri returned to the battalion office Sergeant Zykov was sitting in a chair and polishing his musket. Dimitri walked over to the window and looked out over Ikaphoghar, the mosque minaret, the buildings of the plaza, the tiled rooftops beyond, and the curving shore of Lake Rahar beyond them. Strange country, part of the enemy territory now, bathed in the radiance of a moon so huge and brilliant it seemed to rest like a cartwheel on the horizon.

305Please respect copyright.PENANA5E6tXoa3bX

305Please respect copyright.PENANALsdVFlciSX

305Please respect copyright.PENANAqRJWkn3Dee

305Please respect copyright.PENANASggSK7rGu0

305Please respect copyright.PENANAcvS4v2retu

305Please respect copyright.PENANA5ntYxzlGnS

305Please respect copyright.PENANAd23N7MeRrL

305Please respect copyright.PENANAio38g9Z2m8

305Please respect copyright.PENANATzi8vSeV1Q

305Please respect copyright.PENANA5ocloPQZVN

305Please respect copyright.PENANAR5n5bsW89F

ns 15.158.61.55da2