x

x

The wet blanket of the tropics wrapped itself around each man as he climbed down from the air-conditioned fuselage, the last link with Great Britain, the wife and kids, the pubs, Buckingham Palace, birds, Piccadilly Circus, Big Ben, Brighton Beach.....now, they really were there, sweat rushing to the skin's pores and the odd smell of Vietnam to the nostrils. That circus aroma of animals and sharp animal piss, perfumed blossoms, and the scent of tropic grasses and leaves mixed with the kerosene stench of jet fuel and motor car exhaust.

"They're not gonna put us in those bloody things, are they? If we get ambushed, we've bloody well had it," moaned Kelly, mournfully gazing at the US Army olive-drab buses, with wire mesh over the windows to prevent grenades lobbing in.

"Come on yer whinin' bastard, they're probably waitin' till tonight."

"Yeah, yeah," and he climbed in staring distrustfully at the onlookers, his hand resting on the pack holding his 20-round magazine, thinking, "I'll never get the thing on and cocked in time. Christ almighty....."

The buses rolled out of the Tan Son Nhot airbase into the teeming Saigon traffic: a rushing honking beeping mass of trucks, vans, cars, jeeps, motorcycles, motorized bicycles, farm wagons, converted Lambrettas, bicycles on "pedal power," cycles---a chair propelled by the driver from behind and its motorized version, all training a plume of blue smoke, all honking at each other, and with much arm waving by the drivers, weaving, overtaking, turning left and right, or suddenly pulling over and halting---an ever-changing mass of mobility in a blue haze, peopled by thousands of Vietnamese whose only common feature was black hair and slanted eyes. Vietnamese with round faces, thin faces, square faces, oval and triangular faces, dressed in drab pajama-type clothes---uniforms of green, khaki, white, and camouflage; western suits and ties, western dresses, and the elegant ao dai and dainty parasols for the women; and the universal school uniform of white shirt and dark shorts or white ao dai. The women and girls who walked elegantly, aid dai tails fluttering, or balanced demurely and expertly on the pillion seats of motor scooters and motorcycles, were in a class of their own, as a chic Parisienne or slim Indian woman in a sari are in their own class.

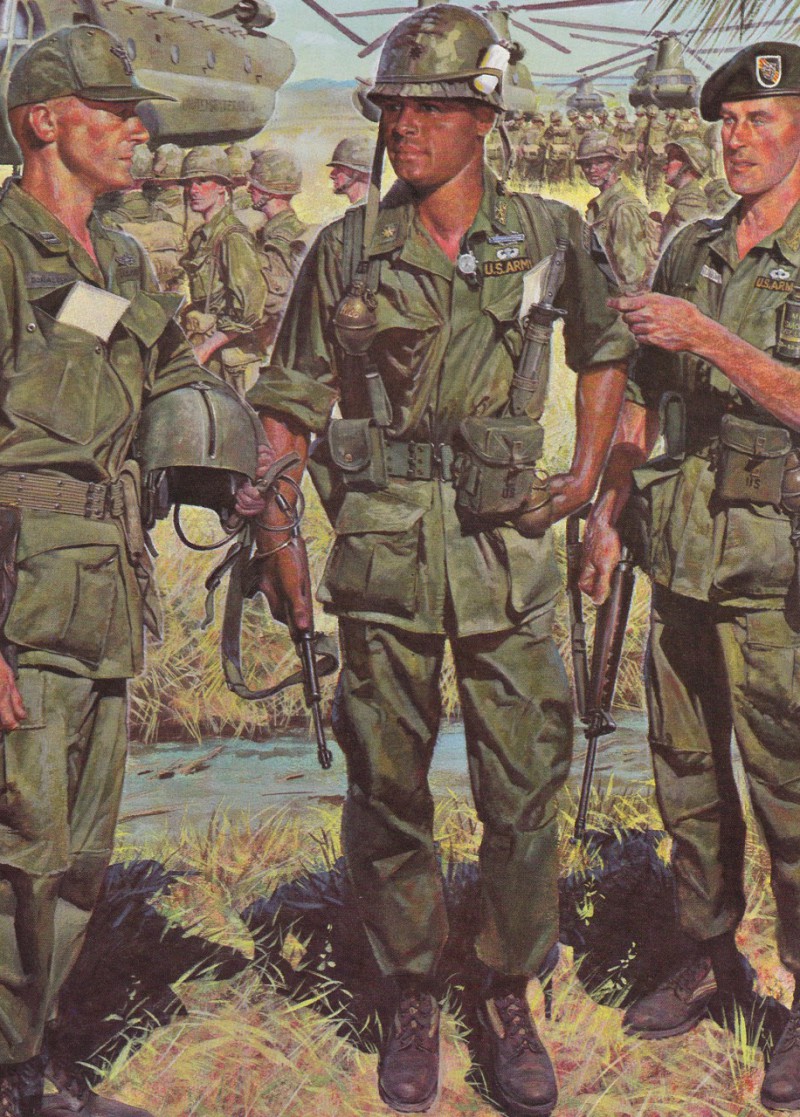

The convoy left the city behind, and its escort of US paratroopers took up position ahead and behind on the highway leading east from Saigon. Young soldiers with brilliant markings on their green uniforms---white parachute wings, white name tags, "US ARMY" in gold, gold rank badges on sleeve and collar, and the universal white T-shirt visible at the open neck of the shirt.

"Look at 'em---like show ponies in field dress---every bit of color gives 'em away. A sniper's delight!"

Driving east along the highway the men were confronted with the flat landscapes of Asia---smooth water-mirror surface of paddies reflecting the peasants walking along the dividing earth "buns"; brilliant green of rice plants; subdued green of shrubs, dark cool green of fruit trees, and strips of jungle; thatch-roofed houses; flocks of white cockatoos starting up and circling; children everywhere running, playing or tending younger children, jumping up and down at the roadside to attract the attention of the ben ngoai for the always popular cigarettes or sweets; adults gliding with the smooth jogging step under the balanced loads at each end of the yoke; in the distance the timeless Asian presence of the small man under his conical hat trudging through the mud behind the round-bellied patient buffalo. Overhead, the birds---both feathered and steel. Against the blue sky and clean white puffy clouds paraded all kinds of aircraft from buzzing Cessnas to roaring Skyraider fighter bombers. Twelve dragonfly shapes of the world-famous "Hueys" threshed their way along, two F100s climbed steeply, underwings laden with streamlined shapes, and circling around and down in all directions were the fat transports---the 4-engine jets and their chubby propeller-driven bombers; the sky filled with silver birds. Later, they would be camouflaged, but now they all glistened in the sun.

The buses trundled through the airfield gate and turned onto a zigzagging red dirt road that followed the perimeter, past the hangar, past the parking area for the Vietnamese Air Force Skyraiders and Cessnas, and the scrap heaps of aircraft destroyed or damaged beyond repair by enemy action or accident; mingled in the pile were the corpses of the B57s destroyed in the recent mortar attack. Standing to the east of the main complex was a building with a square tower on one end like the figure L on its back, an old French post that became known immediately as "the fort." The Vietnamese airfield defense soldiers---a nondescript group in various stages of somnolent ease, ranging from chairs tilted back and feet on the parapet, to hammocks slung under the roof---occupied a series of pillboxes. Beneath the "growth" that had occurred since the French built them, the original pillboxes could be seen: concrete, narrow firing slits and barbed-wire defenses. The Vietnamese had added sandbag parapets around the roofs supporting jerry-built structures to keep off the sun and the rain. The bigger once included chickens, ducks, and families. None gave the appearance of alertness.

Quyền Ngọc Quyên sat under her umbrella at her dusty mobile cigarette stall, a smoking incense stick casting fragrance downwind, along the street leading to the airfield gate. Quyen casually began to restack her wares, and only the most astute observer would have noticed that the number of packs she moved equaled the number of olive-drab buses in convoy that entered the gate. When comrade Loc came later to buy his American-made Pall-Malls, she would inform him how many Englishmen had entered.565Please respect copyright.PENANAm62mpoIIMO

565Please respect copyright.PENANAOtQ8HAVDGd

565Please respect copyright.PENANAfvHDzmzhZi

565Please respect copyright.PENANAwGZZdLqNGp

565Please respect copyright.PENANAorWYvyKfEZ

The buses halted and the men climbed down to find themselves on the inner side of the huge grassy rim of the airfield. Not a tree or bush existed for nearly a mile in any direction---and there was the first problem: since the bunkers and trench systems of Korea, the British Army had operated in woodlands, which, if nothing else, had plenty of trees to which one could tie one's waterproof shelter, or trim saplings to assist in the erection of a comfortable sleeping area. But to be dropped in an expanse of grass with no trees! They stood there, sweating under the blazing sun, straight from the mild British summer to torrid Saigon, baking in the huge frying pan formed by the great grassy depression, no shade, no prospect of any.

The position was a recently abandoned US artillery area, liberally covered with all kinds of debris. Ingenuity in the form of split ammunition boxes, sandbags, iron sheeting, and British entrenching tools soon formed a basis for a variety of 2-man tents.

The afternoon thunderstorms circled the town---not a drop fell on the Britons watching the gray curtains fall from dark cloud bases to mask trees, villages, the airfield buildings, the Vietnamese pillboxes: everywhere, but where it was longingly awaited.

Military matters take precedence over personal comfort, however, and defense against the VC had to be organized.

"Okay, Oscar, you'll be on the right here---hope over and find out where their left-hand pits are and tie in with them," ordered Ben Lowe.

"Right-o." Oscar turned, jerking his head in the direction of the US area. "Daniel, you and Aidan come over as well."

The three strode off through the long grass, rifles carried from habit, balanced on the right ammunition pouch, grasped around the forward woodwork with the right hand. The camouflaged helmet covers of US paratroopers were visible above the grass, marking where the Americans squatted or sat looking out over the area to the east. The closest, alone and with an M79 grenade launcher across his knees, looked up as the three approached, faces shadowed under the broad brims of their hats.

"Hallo, guv'nuh," greeted Oscar. "How ya doin'?"

"I'm in Vietnam. How ya think I'm doin'?"

"Listen, we'll be in the right-hand pits of our crowd over there," gesturing behind, "and we want to tie in with your mob. Where're your left-hand pits?"

"What the hell you talkin' about?"

"Your trench, man! Your weapon pit; your firing position!"

"Oh. I dunno."

"Well, look---where would you go? What would you do if the VC attacked now?"

"Ahh, look. Ya better go see that sergeant, he's sittin' under that tree over theah."

"Never mind," smiled Oscar, "come on, let's get back," to the other two, and all three walked back, highly amused at their first encounter with the legendary US paratroopers: a man sitting in a grassy field, not knowing what he was doing, what his arcs of fire were, what to do if the enemy arrived, and seemingly not interested.

"What the hell kinda soldier is that? Parachute wings, name tags, shoulder patches, rank badges, and he doesn't know shit from shoe-polish!" raged Daniel Serrano.

"Forget 'em. We'll have to put Boone's gun around facing back that way, that's all," calculated Oscar, stopping at the location. "Daniel, you link up on our left and I'll be in the middle."

"Right," said Serrano.

"Okay, c'm'ere you blokes. This is what we're doing tonight, at least. Those Yanks over there don't know what they're bloody well doing, so we'll have to spread out a bit and this is now we'll do it...." His voice rolled on, flat British accent, voice low-pitched from habit after years of training and the long weeks patrolling in Malaya.

The evening meal was provided by American cooks, from the kitchens set up in a half-dug gun position. For the British, it was a hopeful sing of good things to come, despite some items on the menu a little strange to their palates. The unbelievable sight of bins filled with chilled cans of milk in various flavors and assorted fruit juices was greeted with grins between mates and awe in general of the US standard of feeding the troops. The current British supply system was born in the bottomless mud of France, 1916-1918, and bred over the Kodoka Trail, in both places what could be delivered to the front line had to be carried by another man, and so every ounce was grudged. Such niceties as chilled tins of milk never entered the heads of generations of quartermasters, catering staff, or the frontline soldier. For basebludging air force, yes, for the army, no.

After the evening meal, at dusk the ritual "stand-to." Don basic webbing, weapon in hands, occupy the fighting position, and watch your front while the clearing patrols move out from 3 points on the perimeter and sweep in a predetermined direction---clockwise or counterclockwise----to the departure point of the patrol on their left or right, and re-enter the perimeter. Any enemy with evil designs for an attack would be preparing during the last light, or at dawn; hence the "stand-to" at dawn and dusk observed for decades by British forces all over the world. How many millions have lain behind rifle and machine gun as the last light seeped away below the rim of the world, watching the replacing blackness rise up over mountains, deserts, fields, hedges, towns, rivers, swamps, forests, sand dunes, jungles, paddies, cornfields---over every type of terrain and in every climate, and watched the next morning the darkness gather in on itself and retreat as the returning light spilled over and another day started.

And at stand-to, further awareness that the US Army has its own ways: Americans regarding with curious eyes the British silently extinguishing cigarettes, carrying webbing and weapons to shallow pits, and watching the grass in front.

"Hey, what's goin' on, youse guys? Charlie gonna attack?"

"No, just stand-to."

"Stand-to? Oh, yeah." Going on with their unmilitary activities, transistors blaring, car and truck doors slamming, wearing of white skivvies and everything that is taboo during stand-to.

"No wonder the bastards get the shit blown out of them," whispered Aiden Quaid, turning side-on, so his gaze took in Kelly, peering into the gathering gloom at the American contingent cheerfully and noisily cleaning up after the meal, and in the distance the fully lit airfield.

"I thought these bastards were paratroopers---their best. Just fuckin' look at 'em."

"Yeah, I was talkin' ter one today----here he is overseas, nineteen, a paratrooper, a truck driver, and only been in seven months. They can only be half trained, mate. Jumpin' outta planes might prove they're brave, but it doesn't make 'em better soldiers, for God's sake."

Around the perimeter, dozens of other eyes looked over shoulders at the noisy, unworried Yanks, and the fully lit unconcerned airfield, and wondered at the commonsense of these very confident Yanks.

As the night tightened its grip on the world, from all around the flares rose into the sky as men in their barbed-wire posts fired the parachute-borne lights to disperse the shadows for a minute or two and bring a different light to the heart, oppressed by the heavy blackness outside the wire.

The tiny blink as the flare ignited in the sky, then the rapid silent blossoming of the minute sun, smoke trail visible for a short distance as the wind carried the flare and its parachute along, without noise, across the deep inky night sky. So every night, all knight, all around, the flares quietly flowered and drifted across the sky.

After stand-to, sleep, cigarettes inside the two-man tents, or yarns, until time for the 2-hour stint on the machine gun, gazing out over the moonlit grass, glistening silver and ink-black, ignoring the dark figures moving quietly across in front---not "Charlies," as the VC were nicknamed, but Yanks sneaking into town for a drink and women.

The clean-cut American brigade commander decreed that his clean-cut American boys would have no beer or spirits---and nothing more could be knowingly done to incite every self-respecting paratrooper and Briton to begin planning immediately how to get a taste of the forbidden fruit.

So across the sights of the guns drifted the dark figures, following twin wheel marks in the grass leading to the promising land. "Let the Charlies come, fuck 'em. We're gonna find us booze 'n broads in that mother-fuckin' town, man."

Thus had passed Day One.

ns18.223.211.185da2