x

x

A collective murmur of shock swept the Holdings Hall, punctuated by indignant gasps and mutterings denoting a variety of reactions.

At the less-crowded rear of the great room, towards the Hall's great double-doors which, so big and unaccustomed a number of perspiring bodies being present, had been propped half-open for the sake of ventilation, towards the scatter-cluttered edges of the gathering, a thin, shrill scream was audible. With a flurry of motion, one of the guesting women fainted. Others, overwhelming in their solicitude, crowded around to attend her.

A minute passed which seemed to the frightened Zakh like a day in fullness, sunrise to sunset. The Cossacks, through this timeless interval, stood like effigies of carven stone and, it seemed no less than a miracle of discipline to the boy, held their thrust. It was characteristic of the time and place that it occurred to not a single person among the gathering that this might be some kind of a prank.

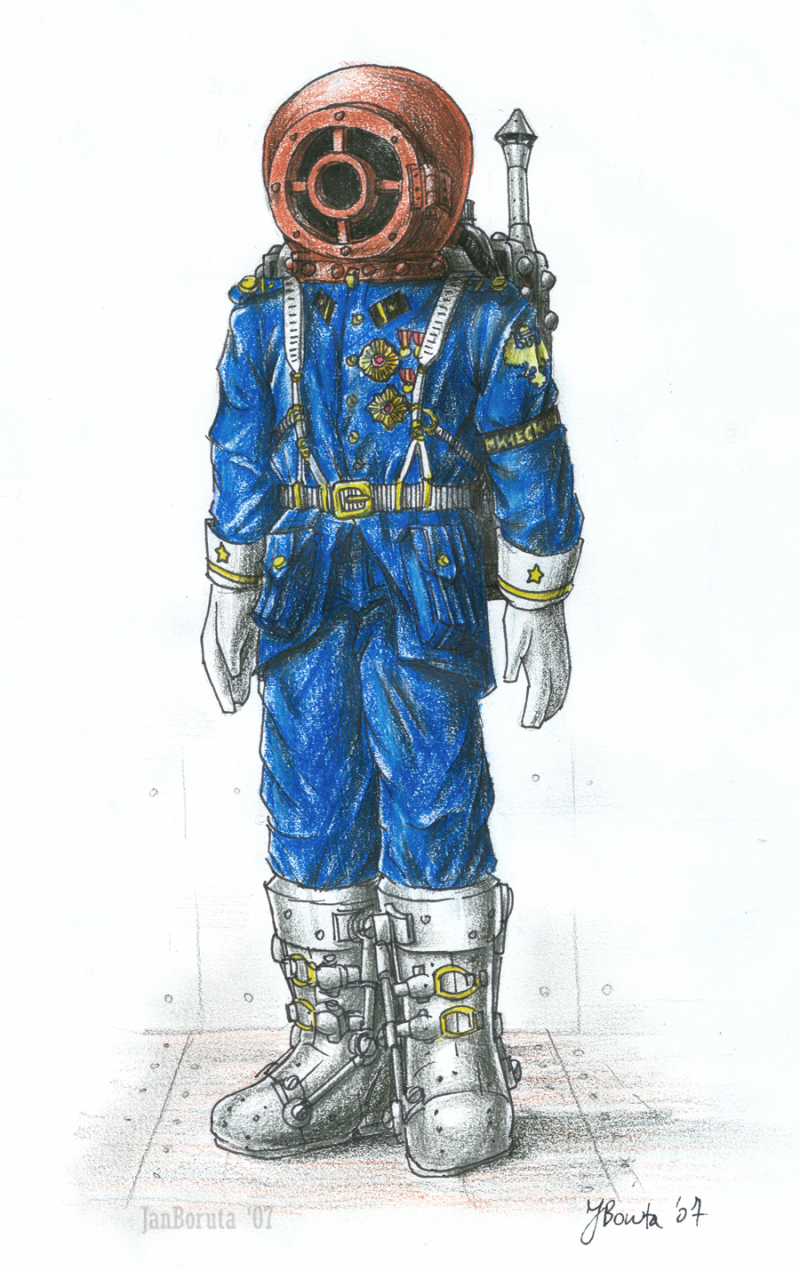

At last, amidst a high-pitched mechanical whine and an accompanying hiss of pneumoplastic tires rolling along the spotless translucent paving blocks, Aidos Zaytseva---his kerensky done away with and the ugly scarlet face of huammurabi ribboned into its accustomed place---wheeled his inexorable way along the aisle which had been cleared in courtesy for bride and groom.

He halted. The noise of his passage ceased with him. He had reached the feet or Eugene fils and Maria Petrovka, standing frozen, much like each of the others in this place, paralyzed with shock, their faces white, their mouths agape. Zaytseva turned in his chair and faced the elder Sorokin.

It was one of those rare moments in the destinies of men which would alter all that had preceded it, likewise, determining everything which was to follow afterward. The look the two exchanged was hard and cold---all present felt it so---more tangible a thing than the destructive energies which the Cossack's upraised quickblades were capable of generating. It could not have been more visible had it been fashioned from a bar of steel. Veronica stood beside her husband, an unfathomable expression upon her insanely beautiful face.

The crippled Zaytseva placed both useless, withered, motionless hands upon the armrests of his chair. With a grunt of expenditure, he pressed his weight upon them, elevating himself a few lines from his seat. By slow degrees, his awkward, atrophied feet slid like the unliving things everyone believed them to be from the treaded metal tray upon which they had so long rested, placed themselves before the chair, and, stirring to life, planted themselves firm upon the key-locked blocks of the floor. Shifting his weight, Zaytseva rose to take a stance upon those feet, separate from the chair which, to all who knew him, had always seemed like a part of his very being.

"You have speculated," Zaytseva spoke as though addressing the crowd about him, yet never took his gaze from the shocked face of Eugene the Sorokin, "why a man might choose, if choose he did, in a civilization capable of nerve- and limb-regeneration, to stay helpless, useless, trapped in and dependent upon an obsolete, noisy monstrosity such as I have just surprised you by abandoning." Now at last although he trembled with the effort, he turned his head, scanning the breadth of the Hall, taking them all in, one, as it seemed, by one. "I have been aware from the first how this marked me in the estimation of many as a kind of freak, maybe physically, genetically incapable of such regeneration, or, far worse, a psychotic, some kind of mystical fanatic."

In a sudden, furious gesture, he stripped the mask of the ancient lawmaker from his face, revealing handsome, hate-contorted features. Gathering composure, he shook his head as if in sorry and turned back to the Sorokin. "As you know----as each and every one of you is all too well aware for the sake of my privacy and self-esteem, I was, in my long-ago youth, a warrior in service to my family Axmadov, my beloved Premier, my revered imperium-conglomerate. I was, as yet, entirely undistinguished, but destined, at least within my own fancy---as many a boy-soldier is in his dreams----to remarkable and valorous achievements." He shrugged. "As the fortune of war would have it, I fell wounded in the first battle ever that I fought, rent almost beyond redemption. It was the selfsame shockingly bloodsoaked incident wherein my comrade-in-arms and closest friend...."

From intonations of reverie and closeness to tears, Zaytseva's voice assumed a sarcastic timber, the sheer malevolence of which made Zakh shiver where he stood, lost in the astonished crowd. It fell to almost a whisper with the repetition of the final phrase, before it rose again. "---my comrade-in-arms and closest friend, the erstwhile classless, penniless, futureless, peasant Eugene Sorokin, became the hero of the day and of the Cosmopolity by virtue of rescuing what remained of poor unlucky Aidos!"

The last few words were shouted. Now silence fell once more. Zaytseva stopped speaking as abruptly as he'd begun. Nobody present thought to fill the oppressive silence with a word or question, even the noise of movement. Stunned, as he would never have been in physical combat, taken aback by the injustice of the accusation, its unexpectedness, by his closest friend's treachery, the Sorokin stood pale and silent as his son.

The Cossacks stayed rigid. Their human officers imitated them, watching with minutest attention every gesture Zaytseva made---when, from strictly tactical considerations, they should have been watching the accused---hanging upon his every word.

At last: "Poor Aidos stayed helpless, at least took measures to convey such an impression, in consequence of a secret, sacred vow of determination. Cruel chance, nothing more, had elevated this unworthy nobody who stands before you, caught out in his misdeeds, to the peerage. Yet, owing to the intimacy of wartime friendship and the advantage afforded by casual conversation in like circumstances, for some time before my personal misfortune, I had come to suspect both his loyalties and his intentions." Showing the strain of standing for so long, Zaytseva inhaled and exhaled. "Yet I was he who, unwillingly that is true, was ultimately responsible for the fame, wealth, and power that he won. Thus, I vowed to set affairs aright myself, staying in this chair where fate had placed me, until my suspicions to confirmed and I could expunge the evil I had unintentionally accomplished, while others, including this upstart himself, gossiped amongst themselves about me and were wrong."

The speaker allowed another dramatic pause, as if gathering his composure for a final effort. "Eugene Sorokov," he rolled the syllables across his tongue as if they were at once distasteful and savory to him, "having fraudulently arrogated yourself to the title Oligarch: in the name, and upon authority of his Wisdom and Autocracy, Murad IIXI, Premier of that august and terrible imperium-conglomerate we know as the Cosompolity of Romanova...." He paused, enjoying the moment, searching faces about him for signs that the ritual was being performed to the absolute letter of the rules. "I arrest you and your renegade, half-bred spawn according to the law of the land, in the presence and sight of numerous interested and distinguished guests, for the high crime of treason, in that you have held and acted upon an overtolerant attitude towards rebellious 'holdouts' upon the Premier's dominion of Genrich, and given ship-sanctuary to his enemies, planet-wreckers, picaroons, and desperados of the Deep!"

Of a sudden, space appeared around the elder Sorokin, evaporate of humanity, as if all who had been at his side now wished to be disassociated with him. It seemed natural that the Oligarch-Honorary and Lady Malinovsyn-Korochuvak were nowhere to be seen. The Lady Veronica, as well--and for some reason this did not shock the boy---had taken several steps backward from her husband, leaving him alone to confront her father's dire accusation. The wry smile upon her lips left no doubt as to the position she would be taking in this affair.

Unaware that he'd acted, and even less aware of what he intended to accomplish thereby, Zakh alone in all the room stepped forward to his father's defense. Scarcely had the boy taken three short-legged paces when he was stopped from behind. A hand descended upon the collar at the back of his neck, took him, swept him up, all in one seamless gesture, into the iron embrace of a slave-warrior at the end of the row of Cossacks. As the breath was squeezed from his lungs, his struggles went unnoticed by the inhuman creature.

Almost the last thing Zakh remembered, as a sparkling red haze descended before his eyes (poor substitute, he thought, with the insanity of hypoxia, for the salute he had so looked forward to) was the gray-green, immobile, merciless expression of the Cossack, the rotten stench of its cannibal breath. What snatched him from the brink, saving his life, was the sound of a scream. One of the officers had fallen upon his face, a stick---a stout tubular knife affixed about the axis of an unworkable Ravina Effeiel, lurched towards the Cossack holding Zakh, and with the slight weight of his body augmenting whatever power his muscles could bring to the task, jammed the bloody rust-toothed point into the creature's rippled back, where kefflar uniform and thick-fleshed ribs covered the kidneys. The blade penetrated no more than two lines, leaving the weapon to stand out from the inhuman soldier's body like the solid limb of a tree.

More from curiosity than pain or anger, the Cossack turned, dragging Terrible Yvan and the weapon around, pawed with one hand at its back, wrenched the Ravina Effeiel free of the bloodless wound, and took the old man by the face, covering his agony-distorted features with the span of its gray-green palm. The fingers closed, blood pooling about their tips, until, with a gruesome noise Zakh would carry in his memory the remainder of his life, the skull fractured at the crown and burst, spewing brain matter in all directions. The Cossack tossed what was left of its assailant at a wall, measures away, where the body struck, sliding down a broad scarlet smear onto the graniplastic floor, no longer recognizable as anything that had ever been human.

Zakh was allowed scant time to mourn the death of his old friend, scarce enough for it to register upon his mind. Jostled by the Cossack, he was reminded of the tokarev-weapon at his side. The Cossack's crushing hold had forced the sash about his waist upward, jamming the pistol into his armpit. With only one of the Cossack's arms wrapped around him, Zakh's own arms were free. Wrenching himself around, Zakh seized the steel and plastic handle of the weapon, jerked it free from its holster, shoved it into one of the Cossack's soulless eyes, and pulled the trigger as fast and as many times as he could. Blood spurted from the ruined eye. The Cossack staggered, its body shuddering.

The crashing multiple reports of the ancient chemenergic pistol filled the great room as no humming quickblade could, breaking the spell of startled inactivity which held everyone in as firm a grip as the Cossack held Zakh. Many things took place at once.

The Cossack let Zakh go and fell dead upon its face, almost crushing the boy a second time. Zakh scrambled from beneath the fallen giant, the weapon smoking in his hand. All about him, people screamed and backed away, disminded and fearful of any unknown, alien device that could overcome a warrior they had presumed invulnerable.

"Zakh!" Eugene fils and his brother Adam dashed through the open space the crowd had cleared for himself and Maria, later for Zaytseva, afterward for Zahk, leaping upon the glittering new riding machines that hovered upon their dormant purge-fields beside the overloaded gift-tables. The vehicles leapt forward, engendering a kind of panic of their own among a crowd that had this day suffered too many surprises, clearing a path. Adam swept up Zakh into the saddle-seat in front of him as Eugene steered towards Maria, having hesitated a moment, thinking first to rescue his father.

"Seize that man for me!" Zaytseva's command was obeyed. Two Cossacks fell at once upon the Sorokin, taking him by the arms, the crack of broken bone being audible to all within the room, forcing him to his knees and holding him there.

"Go!" he shouted to his sons. "Avenge me! AHHHHH-VENNNNNGE-MEEEE!"

This fortunate distraction lent precious moments to the sons' attempted escape. As Eugene fils' machine roared past Mistress Maria---the young man's split-second hesitation had not happened without consequences---she, too, was taken with cruel force by a Cossack who, controlling the struggling woman with one great, gray-green, knobby hand, struck out with the other at the eldest son, fetching him a glancing blow upon the forehead which sprang scarlet.

"Run!" Maria cried. The room began vibrating with unleashed purge-energies. The Cossacks thrust after the brothers, unmindful of innocent spectators who fell like sheaves of harvested grain. Eugene had no choice but to obey.

"I shall come back for you, Maria!" Thus he shouted over his shoulder as both vehicles smashed through the half-open doors and were gone across the meadow before the Cossacks could further act. Zakh's last thought within his father's house was of his pet glob, Zero, locked up and forgotten in the tower bedroom, and of what might now become of him.

Within the Hall, a squad was shouted together. Cossacks being capable of speeds afoot which seldom failed to astound the most sanguine of advocates of machine warfare, and commanded by Zaytseva to pursue the fleeing brothers to the ends of Genrich if need be. As their surviving officer conveyed this in hysterical terms to his gigantic underlings, he emphasized each order with a heavy-booted kick which sank deep into the unrelenting torso of Terrible Yvan lying upon the floor before him. Other Cossacks would follow in the squad's wake once transport could not be commandeered. The brothers would not become aware until sometime afterward how, from this logistical delay, proceeded an infamous and general slaughter of the household retainers and their families, leaving behind one individual in fifty who managed to escape into the surrounding forest, thence into those mountains in which they themselves would soon lay hiding.202Please respect copyright.PENANALIzdp3s2dS

Blotting out Zaytseva's voice and the screaming of the officer, Eugene's words echoed within Maria's mind: " I shall come back for you, Maria!"

"I know you will, beloved," she sobbed to herself, watching the machines dwindle in the distance, unmindful of the hard hand crushing her wrists. "I know you will."

ns 15.158.61.51da2