x

x

"Let the rains fall," Adam Sorokin declared to nobody in particular, "I am nonetheless content."

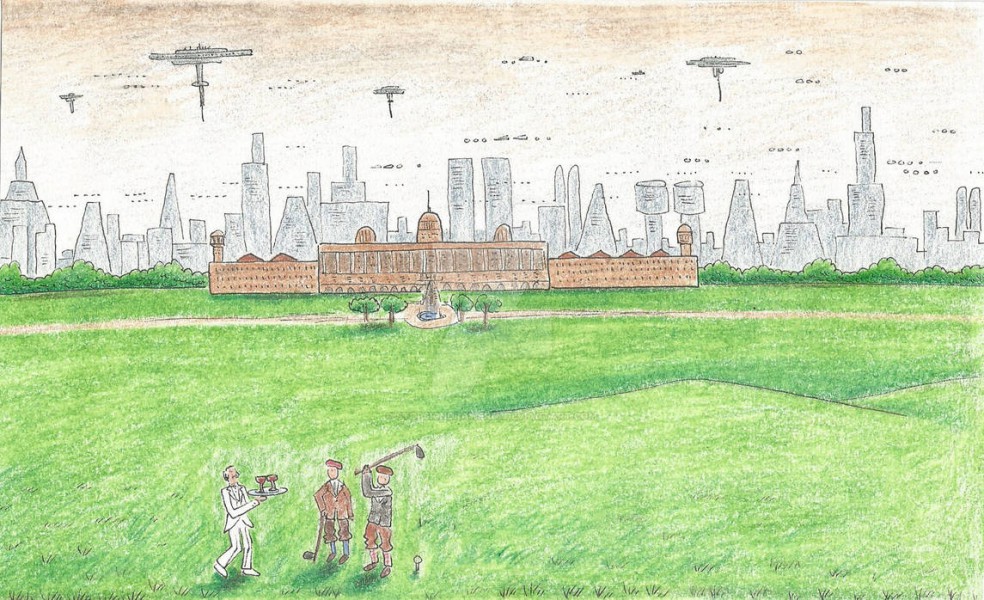

It was a remarkable confession from one unused to voicing his emotions. Tall, broad of shoulder, he claimed that mixture of brown skin, fair hair, and dark eyes under coal-black brows that marked him son (firstborn and principal heir) to the famous warrior-nobleman, Oligarch-Hereditary of Genrich. He gazed out the multi-paned windows of what an earlier era had called a library into the meadow surrounding the holdings.

The day, having dawned unnaturally brilliant, had deteriorated into light drizzle drifting from a gray overcast more typical of the planet. Oblivious to the weather, half a hundred of the Holdings' croppers stooped in the meadow, gathering mistberries and storm-herbs which, later in the season, would sustain them during the perilous sirleaf harvest. Excepting the quaint hats they wore, streaming with moisture, their clothing was identical to the younger Eugene's. Had Eugene Senior been here, he and his family might have joined them in their labors.

"I ask both of you," Adam turned and faced into the room, "how could family affairs be more gratifyingly concluded? Our father, eight years a widower now, remarried this week amidst all the pomp and circumstance which our age, and his station in the natural order, afford...."

"And into a rich connection," intruded a male voice from across the room, "offering limitless political advantage."

Adam hid the sour expression this cynical utterance might otherwise have cast upon his face. What had been asserted was true enough: Aidos Zaytseva, second son of the Oligarch-Hereditary of Boshia, Oligarch-Appointee in his own right, father of the bride, was an old acquaintance of the family Sorokin. In past decades, he had become a powerful figure in the Cosmopolitan 'Stasha. Less lucky than Adam "the" Sorokin, he'd been crippled in the conflict which had made Sorokin a hero and given him an Oligarchate of his own, establishing the current dynasty upon Genrich. That Zaytseva lived at all was the senior Eugene's sole credit. However, that constituted no reason----he broke off the diatribe he'd been about to deliver, smiling instead at a female figure seated nearer by.

"And, heaping fortune upon fortune, leaving me at liberty to seek my own happiness." He lifted a hand towards the voice which spoke of connections. "My younger brother is awarded new responsibility, in which, perverse thought it be, he finds as much satisfaction as I in the prospect of marriage." He glanced up, through the ceiling as it were, towards the old tower. "My baby brother, at death's door not long ago, is now on the mend. Old Hans Petrovka had him up and about this morning, were you two aware?"

Upon a low stool beside the room's modest firegrate (another the size of Zakh's bedchamber dominated the great dining hall) Mistress Maria Petrovka glanced up from the cleverwork held in the lap of her voluminous skirts and smiled back at her fiancé. Her hear, unbound and soft upon her shoulders, was a glossy brown. Her skin, over a frame of delicate bone, was fair where it was not heavily, and not unbecomingly, freckled. Her eyes, blue as Eugene fils' were brown, upon this account were close to black. A hardpine log inside the grate cracked with a startling noise and split from end to end, releasing a thousand short-lived fireflies to dance up the ancient chimney.

Above the fireplace hung the cadet Arms of Sorokin. A modest shield with an asymmetrical straight top and a symmetrical upwards curving bottom, supported by native cronsettos resting on a golden platform. A lavish crown, or coronet, rested atop the shield, it being a crown of heraldic roses with a velvet cap and rows of precious gems decorating the outer sides. Cadet as might be, the shield of the Arms of Sorokin had recently been redesigned to incorporate 4 tusk-joweled Genrichian thrai heads to serve as the emblem, or charge, and a luxurious ribbon, partially wrapped around the supporters, carried the motto: "Profit, Equality, Prosperity." This device was symbolic of the Zaytseva family, therefore also of the senior Eugene's bride, Veronica. Decades younger than the Sorokin---and, some avowed, inhumanly beautiful---she was the golden-tressed daughter of Aidos, once a fighting comrade to the senior Eugene.

Above the shield, upon hooks cast from ancient cartridge brass, hung the original. An awkward mass of steel and green polymer, it made a subliminal statement about how precolonial arms were overcome by the quicklbades of invading Romanovans 100 years ago. Both sides had fallen from mutual exhaustion, the invaders' maladaptation to the planet, and the vicissitudes of a bigger war which had thus far lasted 1,000 years. The Holdings were hung about with many such outdated artifacts.

The burning log settled in its irons, tossing sparks. Maria pulled her skirts from the foot of the firescreen and inspected them for scorch holes and embers before speaking. "Permit not old Hans to hear you call him such. It would distress him, for he repents of youthful days misspent amongst rebellious woodsjacks."

Eugene shook his head. His hair was straight, and being somewhat longer than was fashionable, brushed the collar of his well-worn brownish-green outdoorsman's jacket. "Should I call him by the name the Unsurrendered among his kinsmen give him, 'Hans the Uncled'? It is an ungainly calling, though I have heard it claimed it was a custom in those ancient times, which saw this planet first settled by our Predecessors, that a weaker foe must say 'uncle'----I'll never understand why---for mercy from stronger."

Maria made a gentle noise denoting scorn in one of her gender and breeding. " 'Unsurrendered' do they call themselves, why making mock of one like Old Hans? Your father, I think with too much kindness, names them 'Holdouts.' Are they not those who have retreated, unmolested, to the deepest forest and the mountain fastness, partaking in full of the great oral Bargain he first put to them---thereby bringing unprecedented peace and happiness to Genrich---one of tolerance and, at an arm's length, coexistence?"

"And therefore," Adam gave his tutor's logic a cynical twist, "who is uncle-ing whom?"

"Uncled." Eugene repeated the nonsense word as if he heard neither his brother nor fiance. "You know, that might be a corruption. 'Cowards who have bought their survival through submission.' The unculled. Hideous thought! You are quite right, my dear, I shall never call Old Hans by such a name again, he who was first henchman to Vladisruslan Bogdanov," Eugene had pronounced the name bo-GUN-doff, "leader of the genuine rebels upon Genrich!"

"And," added Adam, "our mother's father."

This time Maria expressed involuntary and uncharacteristic surprise.

"Do you not know," Eugene explained before his brother could lecture, "that my mother, Gabdrakhimovishin, nee Bogandov, came to the Holdings not just out of love, but as a highborn hostage? She, the only offspring of the rebel leader, dwelling in the heart of Romanova-on-Genrich, as it was then known?"

"It was your vehemence that moved me, beloved," answered Maria. "I thought this to have been part of the Bargain. She must have been a great...."

"A great something," he interrupted, "so the Holdouts called her. It hurt her all her life. Sometimes I think that this---not the genetic the sputniks speak of with such eloquence, which made her birthing of us, and our unborn sibling tough----was what killed her at the last."

Silence followed for a time. Never upon previous occasion had such delicate, sanguine matters been discussed between the two brothers, let along with someone else who was, however temporarily, not yet of the family.

"But...." Adam continued as if there'd been no intervening period of silence, as if the thoughts of all three had not wandered elsewhere, but still lingered upon the same subject, which indeed they did. "I brought it up to tell you something else you might not know, nor Zakh, either." He glanced towards his middle brother. "Nor even you, Adam, at a guess."

"What could it be, elder brother, that you've learned that I have not?"

Adam smiled. Even his love Maria could not guess what feelings the expression intended to convey "When Vladisruslan Bogdanov had died---to his surprise of old age and natural causes---and likewise our mother before her time, peace was still fragile and in need of husbandment. Terrible Yvan Dragomilov, not really terrible as his colloquial name suggests, who had been Bogandov's chiefmost lieutenant---came here afoot, of his own accord, willing to become a humble servant in order to take, in some small way, our mother's place as hostage."

Adam's expression was a puzzled one. "Adam, you were quite right. I had not known. Why would anyone do such a thing?"

"I have explained, have I not?" He turned to Maria. "Perhaps you will see that when I called him 'Redshirt' it was in token of respect. Maybe we all---I, too, who has not thought upon these things in years-----will henceforth respect Terrible Yvan the more for it."

Maria nodded and started to speak but was by Adam interrupted. "On the contrary, brother, I disrespect him more who steps from leadership to servitude preserving a bargain made by others, decades old, which maybe did not require to. To 'Redshirt' and 'Uncled,' let us add 'Wastrel'!"

"Only," Eugene suggested, "if we grant you the honorifics 'Cynical' and 'Blackhooded.'" He observed his beloved suppress a grin.

Adam frowned. "Unlike you, my sage and elder brother, I speak of none of these affairs with any authority. They all transpired before my time, not to mention yours. I do wonder why savages everywhere resist those pragmatic philanthropists whose intent is merely to bring them the benefits of superior culture."

"It could be they believe," Maria offered as if Adam's voice had not been laden again with sarcasm, "the asking price of those so-called benefits too dear, even were they given opportunity to bargain or demur." Before Adam could add the words and phrases he'd had in mind, she turned to him. "Nor have I ever heard you speak with very high regard for the benefits of culture, your ordinary term of preference being, as I recall, 'effete eethot excrement.'"

Eugene's reply was half chuckle, half snort. "Much exists, my darling, of which Terrible Yvan might repent himself and does not." He attempted imitation of the ancient servant's voice. "Man did not always sail between stars in mighty ships....' Thus, he fills young Zakh's head with romantic tales of sailing the galactic Deep, enveloped in colorful and subtle auras, propelled by insubstantial sails bellying in the tachyon wind, sometimes being dashed to pieces in neutrino storms." This time the snort was unmixed with humor. "He pursued the selfsame folly with his grandson and namesake and has none but himself to blame for whatever befell the boy in the end."

Maria sighed. She knotted off a stitch, wielded the fiberaser without which no human fingers could have severed the stubborn thread, pocketed the implement, and folded her work around its hoop. "You are the best of men, beloved. I cannot help myself but to love you most immoderately.....'

A faint, ironic cough interrupted her. Adam's brother, seated across the room at the secretary which had become his sovereign domain, was of lesser stature and lighter build than Adam. His hair was thin, sandy-colored, his eyes a paler shade than normal to the family to the family Sorokin. In his bridegroom-father's absence---as, in truth, was more and more the case even in the elder warrior's presence---he was attending the estate's complex accounts. Running the index finger of his free hand along the bands of barcode in the ledger, he paused, adding this brisk notation, correcting that careless computation, turning his flat-tipped ulsic smartbrush one way and then the other, making each precise, vertical stroke the proper width to be read by man or machine. Having heard Maria, he looked up, favoring Eugene with a wry glance.

In Eugene's expression were mixed embarrassment and pride at Maria's confession before a witness. He grinned back, foolish, at his brother, addressing his reply to her. "Pray, Mistress Zaytseva, how could you resist?"

The scowl on her face was merely mockery in part. "If you please, sir, forbear to interrupt. I love you well. Else, after these dreary years in which to sample it, I would never have considered dwelling the rest of my life upon this damp and gloomy planet you Sorokins all adore so."

She set her cleverwork aside upon the woven lid of a native basket, rose, and, brushing at imagined wrinkles in her skirt, joined Eugene at the window. Adam kept his head bent over the ledgers spread before him, but was, without insincere pretense to the contrary, giving them an attentive ear.

" 'We Sorokins,' maybe I ought to begin saying," she continued, taking Eugene's hand. "Yet, for all of that, and more besides, you are most charming in your naivete-"

"Wait now, my girl!" The warrior's son brought himself to full height and shook her hand off.

"Sir," she insisted, catching his hand again, "If you will not take offense at your tutor saying so out of a humble sense of her bounden duty."

"It is true enough and true again," he shrugged. He laughed, seizing her small, soft hand in both his bigger, rougher ones. "Though I might with justification claim my naive appearance to be sophisticated dissimulation. Terrible Yvan says they have no masks upon Genrich and must fashion their disguises out of words. The truth is, I had never a head for history, for politics, for economics of any kind. Like my father, I am..."

"A warrior?"

"I? No. A farmer when you boil down the froth, albeit with a fancy title. Would you undertake, despite the obvious difficulty of the task, the unsuitability of the material at hand, as it were, to educate me?"

She laughed. "Is this not the thing which I was brought here to accomplish in the first place?"

He nodded, smiling as sweet memories welled up in his mind of having fallen in love, unexpected by none but himself, with the "old maid" hired from the capital to be teacher to his brothers and himself. "Da, and I confess that you have educated me in ways I had never before anticipated."

"Eugene" Maria blushed a darker color than her freckles and was compelled to turn aside for a grace-saving moment, although a pleased smile touched the corners of her lips. Adam conspicuously ignored the pair, finding deeper interest in his accounts than had been the case the previous moment. After a time, Maria cleared her throat and assumed a tutorial tone. "For that, darling farmer-when-you-boil-it-down, you shall pay forfeit, and naivete being a curable condition, allow me to earn my keep as a teacher one last time...."

Eugene, knowing her well, shrugged in resignation to the inevitable.

"In the matter," she began, "of cultural benefit and precolonial resistance, few individuals at present appreciate the extent to which ours is an unprecedented period of historic contrasts, of wide-ranging exploration, remarkable invention, intellectual innovation...."

"Amounting," Eugene interrupted, disdain sincere and heavy in his voice, "to no more than the filching and in-smuggling of 'foreign' ideas."

Maria shook her head. "You are the country squire, are you not? Have it your way, for the nonce we shall reverse the polarity of evaluation. Set against all I have described, a dreadful philosophical corruption too base to speak of in decency, a general moral decay which besets long-established institutions...."

"Take care, lady," Eugene aped a sternness of address learned from his father which, in that individual, was no more genuine, "lest you speak treason towards the interstellar Cosmopolity to which the family Sorokin pledges fealty, and whence derive our power, prestige, and privileges."

She ignored him. "---and the territories, celestial, geographical, and otherwise, they have controlled for centuries." Of a sudden, Maria brought herself closer to Eugene, as if beseeching warmth against the weather outside, which could not touch them in this cozy room, or maybe from weather of a different kind, further away and colder. "It is a time, beloved, of reason and brutality, of heroism and villainy, of virtue and depravity."

"In this," he asked, "does it differ from any other time?"

"Agreed," she answered with a sigh, "it is not unique in that regard. What sets it apart, I think, is the degree to which conflicting qualities are found among us, maybe in the fact that they are less to be discovered in conflict with one another than in combination within the same individual."

"Sentimental moralistic nonsense!" Adam sealed his smartbrush with a fastidious flourish, closed his ledger, and turned in his seat to face them. His expression was one of disgust. "Personalities have nothing to do with history. Nor, I warrant, do they...."

He was interrupted by a gentle knock at the room's double doors. Without awaiting an answer, a girl entered with a tray, set it upon a table intended for the purpose, and departed, closing the doors behind her. Maria poured three cups of the steaming drink, known hereabouts as "storm tea," brewed from the same stimulant herbs which the croppers gathered in the meadow outside the window. She offered one to Eugene who took it in both hands, another to Adam, who accepted it without rising, and took one for herself.

"Adam,' Eugene asked after he'd emptied half his cup, "you were warranting something?"

Adam's momentary blank look vanished as memory overcame the effect of interruption. "I was, yes: the human personality is unchanging. It is constant over the eons, and cannot, upon that account, represent one factor in the path history takes. The human personality understands only wallowing self-gratification and the brute force of authority needed to temper it----to print a phrase---into constructive mettle. Thus your savages have no right to resist that which is its own justification.'

Warming to a subject they had previously disputed, he cleared his throat. "Let us eschew sentimentality and be analytical. As is well understood, civilization is characterized by the source whence it derives its energy. In previous ages, animals and slaves, steam and the combustion engine, fission and fusion, powered the fundamental machinery, and thus determined all else of politics and economics, even of personality. So, in our 42nd century civilization is everything desirable accomplished by means of 'purge-physics'---"

" 'A technique," Eugene jumped into the recitation, "of discriminating between fundamental properties of matter---mass, weight, inertia, potential and kinetic energy---and exploiting their separate characters.' Schapiro and Sugarov's Physics The Future, Chapter Four, if memory serves. I know the catechism as well as you, younger brother, Maria taught it to us. And your logic leaves somewhat to be desired, as well. Do not lecture."

Wise in the ways of brotherly disputation, Maria uttered not a word.

"Save your advice," retorted Adam, "for those who have need of it. If Maria taught us, by the Premier, she should know the lesson better herself."

Eugene opened his mouth to say something, but never got a word out. The doors flew wide. In the hallway entrance stood, beside the girl who had admitted him, a cropper, wet from rain and dripping upon the carpet.

"Begging your pardon, young master," the cropper touched his forelock, self-conscious of his clothes, "Zauri Vasifsoy's put the tail of a shadlizard through his foot. We have need of Terrible Yvan before the poison starts spreading."

"By all means." Eugene's answer was brisk. In truth, he was relieved to be given an excuse to leave this pointless argument. He didn't appreciate Adam's not-so-subtle chaperonage. The Genrichian custom---that what he and Maria had pursued with the greatest joy and vigor earlier was now, with the announcement of their engagement, denied them until their wedding night---was an increasing burden and annoyance to him.

He nodded at the servant girl. "Find Old Terrible Yvan and send him straightaway." to his brother and fiancee, he added, "I shall go myself, to see if I can be of assistance."

331Please respect copyright.PENANA1lJGPbol8Q

331Please respect copyright.PENANAZGhDfgERCV

331Please respect copyright.PENANA6biCNOe9ug

331Please respect copyright.PENANAQNvkqUNOOw

331Please respect copyright.PENANAGA4ghnwSmq

331Please respect copyright.PENANAZ53n2SKcWq

331Please respect copyright.PENANA6OZkLGRg2W

ns13.59.22.238da2