x

x

"Sorokin?"

It seemed to Zakh, huddled blanketless again beside the caliprette belowdecks, that he barely slept a minute when he was aroused---albeit in a manner gentler than yesterwatch---by a hand upon his shoulder and a shyly spoken word.

"Sorokin?" Zakh startled awake nonetheless, heart hammering. He would not have been shocked to learn it could be heard by all sharing the gundeck. His inarticulate grunt and sudden movement must have been as startling to the one who awakened him, a thin, ragged boy his own age whom Zakh hadn't seen before. The boy jumped back, out of what he thought was Zakh's reach, and swallowed. Word of what the stowaway had done the previous watch must have gotten around to all hands.

"What do you want? I'm trying to sleep."

"Forgive me....." The words tapered off before an unspoken "sir" as the boy realized he had addressed Zakh as a person of rank. "I mean, Second Officer von Baumbach's passed word he'll see you right away upon the maindeck."

Well, Zakh thought, here it comes. He wondered---not for a moment did he anticipate justice or extenuation----what would be done with fresh meat that killed a crewbeing. Maybe he'd be crisped upon the purge-field like one of the first officer's loaves after all? Or did they have something worse in mind? No, they couldn't. What could they do any worse than what he'd already seen? Likewise, he wondered why the punishment in store for him had not occurred before now.

Thus preoccupied, Zakh nodded to the boy, never realizing it was the reflexive, impatient, condescending gesture of a born aristocrat towards and unfamiliar servant. Nor did the boy, at least nominally Zakh's superior (like everyone aboard the Zilvagabond), understand, in surrendering to Zakh's casual superiority, how he betrayed his own unconscious estimate of their relative positions and volumes more, besides. Had Zakh been ready to understand, he was being informed of the manner in which recent events were viewed by those who had witnessed or heard of them. The sleepy crewbeings all around them (disposed--yet another indication---a discreet distance from Zakh's chosen place) were roused from fatigue-induced torpor by more than curiosity, although the fact was lost upon both boys.

Instead, as Zakh seized the caliprette to pull himself to his feet, a shock of pain washed through him, every muscle---overworked by unfamiliar tasks, strained further by the fight, stiffened by what seemed less than an hour's sleep---screaming in dire complaint. Zakh, who had thought himself fit, was torn between the urge to scream along and a more powerful compulsion to void his stomach. He did neither, maintaining silence by force of character, another unconscious aristocratic act. He found himself awakening to greater alertness than he was used to. Whether this was attributable to the uncertainty of his circumstances, or the difference between physical labor and sedentary lessons, he was in no position to say. Biting his lower lip and inhaling, he brushed shaking hands down the soiled surfaces of the clothing he'd slept in, and---with a gesture similar in tone and meaning to the one he'd earlier given---bade the messenger precede him and followed.

Some, here upon the gundeck, were idlers, supposed neither to be working nor sleeping during this time. They stayed below out of the way of the working watch or to avoid being assigned extra labor. A majority dozed in silence, catching---or accumulating---extra sleep, as was ever the practice of those under discipline, but some were active, telling tall-tales or gambling. At the latrine, Zakh and his companion watched four crewmen drag a young lady, screaming in a language neither understood but obvious in her pleading, from where she had been sleeping, to be gang-raped before the dull, uncaring eyes of any individual on the deck too apathetic to look away. Despite every cruel lesson he'd learned so far, Zakh started forward.

The boy beside him seized his sleeve. "No!"

"Somebody's got to...."

"She's propmarked, don't you see?" The urchin pointed a bony finger at the girl, her screaming now stifled, held by three of the men as a fourth took a turn between her legs. Peering into the gloom for something he did not in all truth want to see, Zakh, numb and horrified, discerned a mark upon her flank.

"Propmarked?" For a second time, he fought the urge to puke.

"Da, propmarked. The biggest, toughest, crew-quarters czars will burn or cut favorites, girls, manlovers, all according to taste. Likeliest her prop's a noncom, loaning her out. She'll learn soon enough: crewwomen that cause trouble get chained to the maindeck hatch for one watch, maybe two, spread to be used by anyone."

Zakh gulped. "For refusing sex, they are given by their...."

"Their prop."

"Proprietor? They are forced to....they are given over to anyone unashamed to take his pleasure in public from an unwilling victim?"

The boy shrugged as if the rising and setting of the sun were being questioned. "There are some who consider it an honor---being propmarked, not hatch-spread---a measure of protection from all users, if you'll pardon the expression. If I hadn't stopped you, you would have been hatch-spread in her place. It's not an end to be desire, as it's a good deal harder upon men than women."

Across the deck, the rapists stood joking with each other, straightening their filthy clothing, and abandoned their sobbing, disheveled victim. Zakh looked at his companion, discovering he detested the sight of the callous boy as much as he detested what had happened. Almost as much as he detested himself for having watched without taking action."

"Upon men, you say?" he asked at long last. The question was rhetorical. He was recalling what had happened to him his first hour aboard the adventurer. "I wonder." With no further word upon the subject, he headed for the ladderwell.

Despite the general disinclination to educate "fresh meat," Zakh had been neither too busy nor too unobservant during his first watch of have learned something of the circumstances he shared with them. Even now, despite his worries and the horror he had just seen, Zakh had more time and composure than heretofore to look around him and absorb the significance of what he had thus far observed.

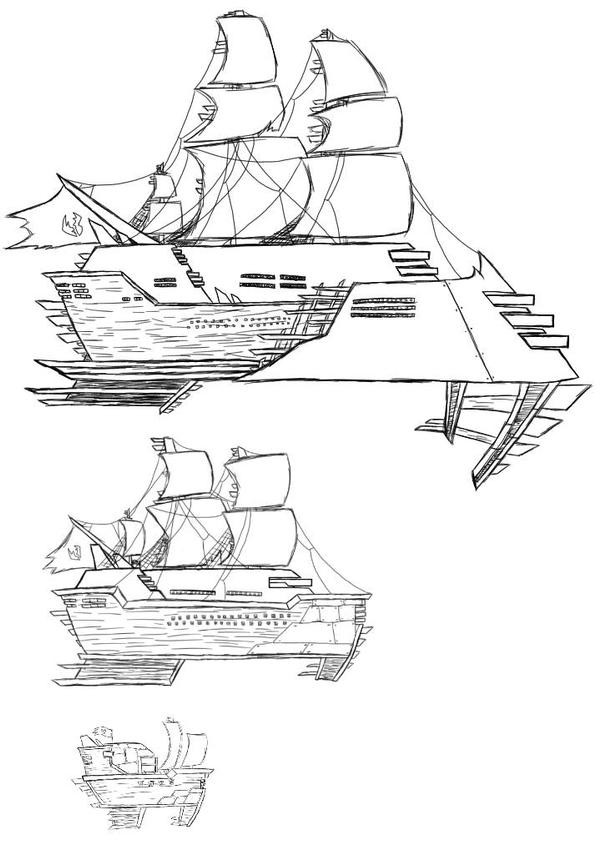

A starship typical of the period, Zilvagabond was an adventurer, a small, swift passenger-freighter of fifteen projectibles' strength, capable of reaching any destination within known space, defending herself against predators, or were it her wont, practicing predation herself. Penetrating all levels, integral with the great length of her mast, were inlaid traceries of metal and silica. The system was ancient and devoid of moving parts. The starsails, impermeable to tachyons which drove her through the Deep, were sieves for other energies. Like the purge-field rider, they trapped quanta, channeling them through the yards to the mast circuitry, which altered them in curious ways to produce power beyond comprehension of an earlier age. Zilvagabond boasted nothing resembling batteries, reactors, or generators, having minimal need to story energy accumulated from the Deep. Her circuitry required scant attention from her crewbeings, the chance of malfunction---save from damage so severe the entire starship would be destroyed in the process---being unheard of.

Divided into levels, Zilvagabond afforded room for passengers, officers and crew, the working of her defenses, and cargo stowage. The gundeck Zakh knew; less fortunate crewbeings, without status, slung hammocks between nine primary projectibles and cargo partitions, for this level was, despite its warlike name, in principle a hold. Also, upon this deck, by the circumference of the ladderwell which was also the foot of the mast, was the galley, at most times padlocked, source of the boxes which had cost Rodya his life. (Zakh discovered within himself no qualm considering the older crewman; it might as easily have been Zakh's life which was forfeit.) The two boys, alike and yet so different, entered the well within the mast, a hollow structure of strong, lightweight material spanning six measures at its foot, whence it taped to but finger's width a verst forward.

Above the gundeck lay the boatdeck, named for six-small atomsmash-powered steam-rockets swung outside the Zilvagabond's hull. She reserved her boats----more expensive to operate than the lubberlift and less reliable---for ship-to-ship travel, hull inspection, repairs, and emergencies. Upon this deck as upon others, ample stowage could be found. Here also were junior officers and less-pampered passengers quartered. Zakh noticed, as they climbed past this level, no sign of a hatch. Access was through the commanddeck alone, a provision to defend passengers (in particular, female passengers) and boats from pressganged crewbeings given to mutiny and desertion. Under different circumstances, Zakh knew he might approve this arrangement. As it was, he understood it, and this seemed sufficient for the time being.

In due course, they reached the level above the inaccessible boatdeck and left the ladderwell. The maindeck they stepped out upon was "outdoors," atop---forward of---the hull. Crewbeings labored here, defended from rigors of the Deep by the all-enveloping purge-field, in what forever had been called a "shirtsleeve environment." When conditions allowed, informal cooking was done here, and it served the secondary purposes of exercise and recreation. The maindeck's prime importance was as anchorage and workspace for thousands of cables, standing and running, by means of which sails were supported and manipulated. Rising to the foremost extreme of the purge-field, the mast boasted three tiers of yardarms radiating outward in as many directions. Starships were oftentimes depicted bearing vast triangular expanses sometimes compared romantically to the wings of birds. Zilvagabond's rigging was at the moment nearly naked, giving her greater resemblance to a winter-barren forest giant.

Had Zakh expected a special reception (beyond question of punishment, the thought never occurred to him), he would have been disappointed. The incident of the previous watch, although not forgotten---nor was it likely to be----was by now relegated to history, no more than another disbelievable item of crewlore. Practical considerations held sway: Zilvagabond still lay above Genrich, the moonring forming a dusty halo about the planet. Much remained to be accomplished by officers and crewbeings before she got underway.

As the boys emerged, the messenger glanced about until he spied the officer who had sent him. Gesturing Zakh to follow, he made a winding way across the busy deck. Mr. von Baumbach, the second officer, was the individual certain others nicknamed Vanya. His duties included those of cargo steward, a task which, aboard a larger merchant-frigate with two decks of projectibles or a military dreadnought with a splendid and intimidating four, would likely be performed by a separate officer. They found him supervising the coiling of cables using a disciplinary aid of the same material. The boy halted---just beyond reach of the improvised weapon, a cynical Zakh observed---announcing completion of his mission. Von Baumbach eyed the boy as if searching for an excuse to stride forward and strike him. Finding none, with a disappointed expression souring his thin-lipped, arrogant face, Van Baumbach dismissed him.

"Sorokin." Zakh's name, as uttered, carried not the slightest intonation indicating what the man meant by it. Zakh had yet to learn that this was a species of cruel art, practiced to refinement by officers of this and other ships. A word thus spoken might encourage a guilty crewbeing (even one who wasn't guilty) into reading too much into it and betraying himself.

"Sir." This courteous appellation was delivered with equal (albeit unwitting and reflexive) neutrality, as none but one reared as an aristocrat might manage. The bodily attitude which the deliverer assumed, of stiffened attention, was something Zakh had in recent days learned for himself.

"Sorokin, against my better judgment, I am ordered to elevate you from the gutter where you rightfully belong, and attempt---in vain, I assure you it will be---to make more of you than you'll ever make of yourself."

"Sir?"

"Do not take an innocent tone with me, you murderous prick-teasing little manlover! You are qualified for one duty alone, as far as I can see, one which, however grudgingly, you have already performed. Were it in my hands, which, to my deep regret it is not, you would be safely disposed of and forgotten. Yet you are to become a ship's boy---at the behest of Mr. Dracul Putin---like the one who brought you here. Is that plain enough for you?"

Zakh tried to straighten his tired body, to stand more at attention than he was. He sensed this as an urgent necessity. Although his words were delivered in a harsh whisper---a bellow only by intent---and von Baumbach's expression was coldly superior, what Zakh saw, deep within his eyes, was disbelieving terror. Men, he had learned from his father, capable of such disminded fear, were dangerous. Something even more dangerous---deep inside Zakh---chuckled to itself.

"Ware the margin!"

"Idlers below!"

"Rigging hands aloft!"

Shouting seized the attention of both man and boy. Despite what he'd suffered aboard her, Zakh held Zilvagabond to be a wonderful thing. He had once, before reality imposed the choice, imagined any starship a better place than planetside. Now, standing at the foot of the quarterdeck still undismissed by her distracted second officer---and upon this account not technically among the idlers ordered belowdecks---he beheld a spectacle to make all previous pale by comparison.

Devices employing electromagnetism---the motors driving Zaytseva's chair---could not operate within a purge-field. It was expected by those like Zakh, whose education permitted them to speculate without engendering sufficient cynicism to damage their belief in progress, that someday purge-motors might be invented. Some visionaries (this, too, included Zakh) believed that purge-fields themselves might be used as starsails. Meanwhile, working a ship such as the Zilvagabond remained labor-intensive. Uneducated and unspeculative sailors placed faith in the steam-winch (in sparing usage, as it consumed precious water) and in high-advantage hoists upon the maindeck, along mast and yards, and in their own impressive courage, strength, and skill.

Amidst shouted incomprehensibilities, dozens of men and women scampered aloft with a semblance of enthusiasm. Some climbed the rigging, which seemed to stretch from every portion of the maindeck into the complicated webbery of cables overhead. Others scurried to the platform where Mr. Putin had stood. In an instant they were whisked up the mast, outdistancing the climbers, until they and the platform seemed to dwindle in the distance and vanish.

More commands were issued, relayed by high-voiced juniors stationed at intervals along the mast. With a titanic skak! the first of the voluminous triangles unfurled between two long yards at the mizzentier. Another opened thunderously, and another. Higher aloft, crewbeings spread the triple suit of the maintier and the foretier, while others manned curved staysails which stretched in a staggered spiral from tier to tier.

Hove to, her modest requirements had been provided by a few smallsail, all but invisible from the maindeck, which kept her upon even keel and fed her galley. The lubberlift, regaining in the downward voyage most of what is consumed in the upward, required little to make up losses all machinery suffered. Now, purge-fields heretofore maintained in somnolence roared and flared where they encircled the quarterdeck taffrail, dazzling Zakh, making his eyes water. Augmented brilliance crept like a living thing, measure by inexorable measure, up the rigging, forward along the mast, into each of the sailtiers in turn. The adventurer Zilvagabond was cast off under all plain sail.

Zakh glanced back at Mr. von Baumbach. The man gave him a speculative eye. "I can, upon the other hand, select the manner and condition of your training, Sorokin. And I believe I know what is in the best interest of the ship." Whistling between his teeth, he summoned the boy who had brought Zakh to the maindeck. "Pass the word to Mr. Mikoyan. I wish to speak to him before he takes trainees aloft. Tell him I have another for his practice squad."

Hardened as the ship's boy might have thought himself, he glanced at Zakh, pity written in his eyes. He had seen crewbeings ordered aloft in a neutrino storm, when wild undulations along the mast and unpredictable vibrations in the yards threw them off into the purge-field, and, in precaution, double the number were sent aloft to replace them. Once, as part of a handful being punished for an offense committed by one of its members (when blame could not be assigned---sometimes even when it could---such punishment was ordered to weaken mutual support among the crew), he had been required to report upon the maindeck every hour for forty watches.

The second officer seemed gratified when his victim grinned in agreement, for the man was fooled by what he took for naive enthusiasm. It had always been a mystery to him why an individual, pressed into this horrible vocation, would prefer the miserable and perilous estate of a humble crewbeing upon a starsailing vessel to an alternative which, however desperate and final, was, given the multitude of means at hand, easier and more comforting to contemplate. Maybe a solution lay in the very peril which characterized life aboard a starship, for attrition among new crewbeings was enormous, leaving only those behind who loved life well enough to endure its agonies.

Zakh may have been one such, although for him the greatest hardship he anticipated, aside from what had befallen him upon what he now knew as the liftdeck, was the utter impossibility of sleep. Not only had he the other members of the crew to fear, he and others might be turned out at any time for drills or extra duty. Perhaps the boy labored beneath a burden of what he looked on as unfinished business, to be honorably disposed of before he might, in decent conscience, consider easier, more comforting alternatives. In any event, ordered aloft despite muscles aching from the previous watch (as well as his fight with Rodya), he went to it with an outward exultation which might have shocked anyone interested enough to be aware of it. That his attitude actually owed its existence to the identity of one going aloft with him escaped Baumbach, despite the fact that he had sent Zakh (nor was Zakh unaware of it) to die. Heading the practice squad was Zilvagabond's third officer, Mr. Kharkov---better known as "Vanya."

For Zakh it was a quick, easy climb up the ratlines, ladderlike contrivances anchored at the afterends to the maindeck. No crewbeing was ever sent far aloft the first time---the 3 great yards of the mizzentier were closest to the maindeck, not more than several dozen measures above it---intended, as the exercise was, to provide them with basic instruction in the working of the ship. Yet it was safer only in a relative sense. A fall from this height would kill with the same finality as any from the foretier, two thirds of a verst higher.

High in the mizzentier, Zakh and other neophytes were ordered to space themselves along the yards, each of three squads supervised by a seasoned hand. It was intended that they should practice furling and unfurling the starsails, and to this purpose some worn expanses had earlier been set upon this tier, great volumes of mesh sheerer and more flexible than that of which the hull was made. In this they were assisted by the footcable, of several gleaming strands, not unlike that from which the lubberlift depended, running through stout eyes attached at intervals to the aftersurface of the mizzenyard, and upon which, as might be imagined from its name, they placed their feet as they hung their arms over the yard and shuffled crabwise along its intimidating length. Veteran crewbeings eschewed this artifice of amateurs, preferring to run barefoot along the smooth upper surface of the yard. With equal spirit, they scorned the ratlines and scaled instead the cables like vine-climbing arboreals in some storyfile jungle of Zakh's childhood fancy. The boy believed a long time would pass before he would count himself among their number voluntarily.

No sooner had this passed through Zakh's mind when the 3rd officer made it plain that "voluntarily" would never be a word in currency aboard any ship for which he was responsible. With a sadistic chuckle, he inspected the green countenances of the dozen crewbeings allotted him for the drill. Strung along the mizzenyard, they clung with a loving dedication never demonstrated at their mothers' breasts. The cable danced beneath their unpracticed feet. None---including Zakh, who, save Vanya, had taken the position closest to the mast (suiting the 3rd officer's preference as much as his own)---was capable of contemplating anything except the blessed moment when they might be allowed to return to the comparative comfort and safety of the maindeck below.

"Here, timorous tartlets," he laughed, "is where we separate the living from the soon-to-die!" Swinging his right leg over the mizzenyard, Vany let his left foot---bare as that of any crewbeing, long-toed, with spurred and hardened heels---slip from the cable. Holding the yard with his right arm, he leaned down, undid the shackle, attaching the inboard end of the cable to a turnbolt upon the mast and began jerking at it.

Zakh was alert, fear forgotten in a wash of something hotter, cleaner than the terror which, seconds before, had dominated his being. Man and boy were blocked from sight of the others, not just by the uncontrolled flapping of the practice-sail, but by the crewbeings' fear, not a whit better controlled. Zakh watched and listened, calculating. Vanya opened his mouth to speak, Zakh could hear the preliminary catch of the 3rd officer's indrawn breath. Before it could be completed, Zakh jumped hard upon the cable, letting it take his weight, all but letting go of the mizzenyard.

The cable, no longer shackled, screamed outboard, taking Vanya with it. Its turnings, whistling with friction, it ran through the eye between the two of them, dropping Zakh his full height and whipping Vanya around, tearing his arm free of the yard. He hung but for a moment by the callused spur of his right heel. His own arms pained by past effort, straining with what was demanded of them now, Zakh scurried up the cable, regaining purchase on the yard. It was an instant that seemed to go on forever: Vanya still held the free end of the cable in his right hand; his trembling left reached towards Zakh; a pleading expression was on his face.

"Help me!" Another lifelong moment passed.

Zakh whispered, "None of that, now, sweetheart!" and let Vanya's whitened fingertips slip through the air a line from his own. Vanya's heel left the yard, his face yanked from Zakh's view. Once his desperate appeal had escaped the doomed man's lips, he was quiet. Accelerating as he fell--for some reason he continued holding the cable---his course deviated, becoming a steep curve as the cable, stopped at the bolt nearest Zakh, shrieked as it reeled slack from the yard and altered his fall. Instead of plummeting to the deck, he swung toward the purge-field. As he struck the limit of the cable's slack, the shackle was ripped from his hand. He continued onward, outward, and---with a huge, dull pop! and a flash of light---the Zilvagabond's 3rd officer vanished, vaporized like one of Mr. Putin's loaves.

Right, Vanya, Zakh thought. Inside, he was empty, experiencing nothing he could have named save for the mildest sense of satisfaction. Here is where we separate the living from the soon-to-die!210Please respect copyright.PENANAMnUIkEXFPV

It was a philosopher of crime, renowned for intelligence guided by experience, who observed that killing is best accomplished spontaneously, when means and opportunity are present by fortuity. Never having heard this advice, Zakh had nonetheless acted in a manner consonant with its sagacity.210Please respect copyright.PENANAG2PK18Xr4K

And thus became a ram among the sheep.

210Please respect copyright.PENANAee0XNc0AvI

210Please respect copyright.PENANA9hlhQ3ZED6

210Please respect copyright.PENANAE8nW0XLGZb