x

x

As Oswald Arison lay on his bed, the hands of death slowly creeping up to caress his face, his final wish was simple. He wanted his greatest accomplishment to not only stand strong through the ages but to have his blood forever live with it. So, just as his attorney and dearest friend was melting the wax seal to Oswald’s will, he scratched down one more line,

“May there be a member of the family attend the Arison academy with each passing generation.”

The line at first was almost throwaway; meaningless. His two sons, Bruce and Sawyer had already attended the school Oswald had so meticulously run, and Bruce’s son, Mordred, was already set to go. There was never a doubt that every well-fit young man from the age of 12 to 17 would head over to the prestigious school in their own name: The Arison Academy of Excellence. For over eighty years, Oswald’s rule was followed with what appeared to be gracious ease, but in reality, the foundation was slowly cracking and nothing could be done about it.

Generation 1: Sawyer had died of the white plague before having any children.

Generation 2: Mordred had a sister, who, torn apart by her family’s continual expectations and warped view of a home, fled to the Seychelles islands and was never heard from again. Upon hearing the news of his missing daughter, Bruce Arison simply shrugged his shoulders and huffed,

“Her children will not be Arisons anyways.”

But the final nail in the coffin was with the only remaining Arison heir, Mordred. He had never failed to make his father proud and quickly got married after finishing his studies at the academy. There were murmurs of him, “rushing into things,” but in Mordred’s eyes, it was not only for the sake of the family… but for true love. Not less than a year later a baby was on the way. The nursery was already painted a pale blue and filled with toy doctor kits or number-teaching books; everything their little boy needed to be the next shining face of the always successful Arison line. Yet the nursery was nowhere in sight when the storm would arrive.

It was an early delivery. Despite all of the doctors’ assurances and tests, that torrid day on a Spanish hillside was when the baby decided they were done with waiting.

“Mordred, dear, do you think we can eat this?” Adelaide called to her husband, who was busy flipping through schedules coated in scribbled ink and colourful stuck-out tabs.

“I wouldn’t,” he reprimanded to his wife, just as she reached out to pick a bright magenta bulb from a cactus. He flicked another tab down on his planner.

“We need to get going, we’re too far off course.” Mordred continued, gathering their hiking bags to depart. No answer. He looked up, and saw his wife clatter to the ground.

“I told you not to eat that! You’ve gone and poisoned yourself!” Mordred said, his face growing the same colour of the fruit as he hobbled towards her. But Adelaide shook her head, her eyes wide.

“It’s the baby, he’s coming.”

Mordred’s heart seemed to sink into the sand below. He might as well have ripped the pages out of his schedule and used them as fertilizer for the cacti since it served no other use. No plans, no warning, and not an inkling of what to do next.

Somehow, things were brought back to a sense of order when Spanish locals joined in to help the labouring woman and her erratic husband, bringing her shelter and plenty of water. It was not long before the delivery was complete.

Mordred smiled for the first time in a long time at the birth of his first child. He beamed in the heavy light of the late afternoon, his back cast in shadow as a weight seemed to be lifted off of it. The blood of Arison would live on, and Oswald’s rule would be carried for yet another generation—

“A beautiful baby girl!” Adelaide cooed, finally holding the baby in her arms. Mordred’s smile faded at once.

A girl it was, with her father’s harsh ink hair and her mother’s eerie emerald eyes. And she was named after the very fruit her mother was so tempted to eat before she was born. The locals called it prickly pear in English, but that wouldn’t do. They settled on the Latin genus name: Opuntia.

“Opuntia,” Adelaide smiled to herself as she rocked her baby back and forth, while Mordred was retreating farther and farther into the icy trenches of his mind. Little did they know that prickly pear was also known as, “the devil’s tongue,” and a devil’s tongue their daughter would have.

Opuntia wasn’t aware that she was unwanted at a young age. She at first was delighted by all the talk of immediately having a younger sibling, a little brother. She bounced around as a toddler as her parents went through test after test and procedures. She giggled as her mother set her down in her crib, before turning to her husband solemnly.

“You heard what they said, what if I don’t want to risk it?” She murmured, before switching off Opuntia’s bedside lamp. “I’m ill, Mordred, I can’t keep doing this.”

“I promise, my love, this will be the last time. But we have to try…Arison--”

“It’s all about you,” Adelaide snapped at him, closing the door shut behind her, but still talking fiercely enough that Opuntia could hear her loud and clear.

“What if I died? Would it be worth it then? If you had your son for your stuck-up school, would you-”

“One more time, Addy, darling, please,” Mordred said to her, clasping her hands in his. “We have to try,”

They did try, and Opuntia knew this. Miscarriages through miscarriages finally gave them another life, but the amazing gift of life was not amazing enough for Mordred Arison.

“And the sex?” He asked the midwife, mere seconds after the freshly born baby was picked up by her.

“You’ll be happy to know it’s a baby girl, perfectly healthy is what matters most.” She beamed. But the look on Mordred’s face showed that he did not agree.

Halle was born two years after Opuntia. Opuntia remembered poking her head around the corner of the bedroom to see a crowd of women adoring and caring for the baby and her mother, but shrouded in shadow, simply smoking a funeral cigar, was her father. She didn’t understand. She thought he was a monster, that would snatch at the baby from the shadows if it wasn’t for the midwives’ protection. She remembered being upset that she couldn’t see her mother, who was bedridden for the next week. She didn’t understand anything then, that was a curse that would follow her around like her father’s smoke. Billowing thicker and thicker around her and her parents. She watched her father pace his study and bury his nose in books instead of playing with his children outside. She watched him from her frosted window in the early hours of the morning as he drove away to the looming boarding school up the hill. The school that looked like it was scratched to life with a pen, with its sharp turrets and tagalong church house next to it, wearing evergreen trees as a coat. She didn’t know why, but Opuntia’s eyes were always drawn to it, even before she fully knew what it was. She was just told that it was a place she would never step foot in, but that didn’t stop her from dreaming.

She’d make stories and play games that took place there. She, her school friends and sometimes her sister would jump from tree top to tree top, trying to rescue each other from the clutches of Dracula, who obviously resided there. She’d even brag to her classmates that the school was in her name, but most of them were never wowed.

“Who cares?” scoffed Michael DeAngelo, “That school is for boys only. I’m going there next year, and you’re not. Now THAT’S something to brag about.”

He was right, after all. No girl had ever gone to Arison Academy, and she knew that. But it didn’t stop her from trying to kick Michael in the knees all recess long until her best friend had to drag her away.

“Why do you have to listen to Michael? He’s just a bug,” he said exasperatedly after finally letting her go. Teddy Dodgerson. Their families had known each other since before they were born. They were like two sides of the same coin, the one that everyone liked, and the one that everyone was afraid of.

“You better not be talking,” Opuntia replied, crossly. Teddy was also, of course, going to Arison next year, leaving her at the New Versine junior high.

“I know it’s dumb, O.P,” he sighed, wiping the sweat from his brow after dragging her across the schoolyard. “But, you know… it’s just the way it is.”

“Do you know how embarrassing it is to have my name, here, while groady boys like Michael get to go to the academy?” She knew she had the grades, and she had the connections, even the wealth to go to that school, but there was just one thing stopping her.

Teddy, in Teddy fashion, knew when to stay silent. He shook his head sadly just as the bell rang.

But little did Opuntia know that the great Arison Academy was closer in her reach than she had thought.

As the next school year grew closer and closer, the summer slipping away through peachy skies and weather moderate enough for New England, Mordred was also slipping more and more. He had more hushed conversations with his wife, speaking in quick, panicked voices that they thought no one could hear. But Opuntia listened with a glass to her ear, hiding from the maid and the cook’s disapproval.

“There’s no one left, Adelaide, no one. Oswald’s rule will be broken and I will be a disgrace to my family, do you not understand this?”

“Mordred, darling, it’s out of our control. We tried everything we could, I assure you no one will blame you.”

“I can feel his disappointment now,” Mordred said in a pained whisper, “I can feel his eyes boring into me. I can’t take it,”

“What are you doing?” Halle was suddenly at Opuntia’s side. Startled, she dropped her cup and let out a string of curse words as glass shattered all over the floor.

“Go away. I’m busy.” Opuntia snarled. Halle could never get off her sister’s back.

“Well, you’re supposed to be in bed, and you’re not. So, I get to be up too.” Halle concluded, crossing her arms and pouting in her nightgown.

Opuntia rolled her eyes at her sister’s “indisputable” logic.

“So…What are they talking about?” Halle asked, leaning into the door as Opuntia feverishly picked up glass shards.

“Well, thanks to you I have no idea anymore,” she grumbled.

“Oh, really? I was watching you for 10 minutes, so if you don’t tell me, I’m telling them.” Halle pointed to the study door, then lifted her hand up to knock.

“Alright, alright, don’t be a fink,” Opuntia said. She explained “Oswald’s rule” to her sister, and how it was dangerously close to being broken.

“…So that’s why father seems so on edge lately,” Halle said in a more serious tone.

“More like our whole lives,” added Opuntia.

“Well, you aren’t thinking of going, are you?” Halle asked

“Don’t be a ditz. I’m a girl,” Opuntia said, though it pained her to say it. But the more she thought about it, the more she stood there in the hall, painted white against the oak study door, she thought that this could be her chance. Her father was backed into a corner, and for once, she could swoop in and be the child he always wanted. She was so lost in this epiphany that she didn’t hear her parents walk to the door. As Halle scurried away just in time, light flooded into the hall as the study door swung open.

“I can go to Arison. I can keep the tradition.”

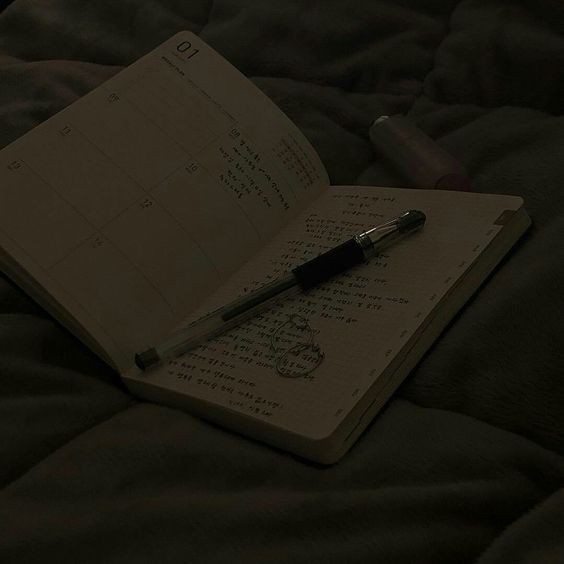

It wasn’t easy convincing her parents to let her go, or the school board, or the principal (since it wasn’t her father). After a long and tedious examination of Oswald’s will, it was concluded that it never specifically stated that it had to be a boy from each generation, just a member. It was Opuntia’s golden ticket. But this story isn’t about her first year at Arison, the struggles she faced, or the wild looks she got. It wasn’t about her second, third or even fourth. It was her final year of Arison Academy. The year was 1970. The Beatles had just broken up, and there Opuntia was, with her trunk packed to the brim once more. But she wasn’t getting the sleep she needed before her ascent to school in the morning. Instead, she was lost in her own mind and writing down on a fresh page.

She never needed much for her new school year. New pens, pencils; an eraser. But the thing she always asked for, without fail, was a Florentine leatherbound notebook. She kept it hidden away, deep in a desk drawer or stuffed under her pillow. And in there were the secrets of her heart.

Why do stars shine brighter just as your beauty dies?

Their distant light glows higher, celebrating my demise.

For the summer sun can no longer be admired from outside,

but fractured through a window pane, and absorbed by tired eyes.

Eyes that flicker wearily into the depths of another page

full of equations and endless words nearly forgotten by the age

Yet I know I worked so hard for this, so how can I complain?

Maybe stars celebrate my final year…

of being locked in my own name.

-O.M.A

ns 15.158.61.22da2