Betz Langdon saw very little of her neighbors over the next few years. She left them to mourn, but would leave bottles of booze at their back door sometimes during holidays that were no more, or just when she sensed they needed to get batshit plastered (the blame and accusations that go hand-in-hand with loss of a child might have wafted through her open kitchen windows).

She remembered decades back to some of the blowouts her and Eldon had had but once the fur settled, would hit the Circle C together and drink and laugh and, after last call, do the dirty. She was gonna try like hell to salvage her friends’ marriage, she told her grandson Billy, and liquor is quicker. Cackle.

Betz’s concern was not unwarranted–”statistically, 80% of marriages where couples lose a child end in divorce,” the grief counselor who welcomed Jack and Julia to the therapy group was quick to mention. The Mayhews, buoyed by the eternal optimism, left during the first break and opted out of the therapy group for good.

Life got worse: Julia was fired from her factory job. Her work was adequate, HR assured her, but other employees had complained about her “having emotional issues.” Ya think? The union that Julia had supported for 11 years supported the accusers; the rep, a co-worker and former friend, took her key card, yawned, and showed her to the gate.

Jack saw what professional entertainers had to go through--laugh tho your heart is breaking--backstage at the television network many times, but now it hit home as he had to continue his radio role as the congenial Fatboy.

Most of the songs he spun, blasting lyrics like “Iiiiiiii wanna rock-and-roll all night, party every day!” seemed pointless and stupid and somehow, a personal affront. And the irony of it all was that he, who probably earned every right to drink every drop of Stolichnaya vodka in the studio, remained sober through each minute he was working–it was the owner, his friend who brought him out here and who was rolling in money because he had created an entity that was number two in market shares--who was now drinking it straight up and on the air.

Jack was discouraged and distraught; earned the scant dinero he was being paid. As best buds, it never occurred to him to sign a legal agreement about anything--it was all about just starting the station from scratch and having some fun like they did in LA. As the money poured in, though, Jack just assumed that he would share the wealth, although his only raises were the use of the company credit card for gas money for the hour drive down and the hour drive back home again, and the hackles of the drunk asshole whenever Fat played a song deemed not permissible.

Music was not Jack’s refuge, it was his job, and he got through each shift okay because he had to, with Julia’s union wages suddenly replaced by unemployment checks. His relief was the quiet darkness of his after-midnight drive home--radio off, wondering how his life became this nightmare, worried sick about his wife, anxious about the growing stack of bills piling up, exhausted from the fights and recriminations, hopeless about the future, grieving for Julia and Angie’s grandparents. Panicked over ‘what the fuck next?’

Whenever he did need his own emotional musical release, he did it with the Stone’s mournful tune, Blinded by Rainbows--lyrics that mocked his whole fucking stupid idea of maybe, just maybe, finally living “happily ever after” was possible the first time he crossed over the fucking river to here. Lyrics tinged in Jesus, emoted by Jumpin’ Jack Flash:

“Did you ever feel the pain

That he felt upon the cross?

Did you ever feel the knife

Tearing flesh that’s oh so soft ?

Did you ever touch the night ?

Did you ever count the cost?

Do you hide away the fear?

Put down paradise as lost?

Yeah, you’re blinded by rainbows,

Watching the wind blow.

Blinded by rainbows.

2

By 1997, Eugene was mostly a stay-at-home hermit, and who could really blame him. It didn’t take long after the shitfest for him to know with certainty that he was now the laughingstock of the town that he loved so dearly.

Wherever he went, it seemed to him, folks would greet him politely enough with an Eddie Haskell-like, “How ya doin’ Mr. Rathbun?”, but then he could see shoulders shuttering, heads rocking back and forth a bit--sure detections of building laughter--when they turned to walk away. He and Winnie also dropped out of United Methodist, reminding himself that the ruptured septic tank was probably still good for a few good laughs at church get-togethers, especially during summer socials and the breaking out of their goddamn soft-serve ice cream machine.

Now Eugene was sending Winnie down to the lumber yard for building supplies, employing and instructing the Amish from McDonough County to add doors that went nowhere; to replace the stairs in the back hallway with odd-sized steps; to install windows that overlooked drywall; to install a toilet in one of the closets without plumbing (less chance for another blowout, is what he told her).

The workers—straw-hatted, hand-sewn-denim-shirt-and-dungaree fashionistas—put their noses to the grindstone (literally sharpening their tools on them) and never openly commented about the work they were doing up on Rathbun Lane, but then maybe they think modern society is over-indulged and neurotic with our electricity, luxuries, computerized gadgets, and such. Those dedicated to the 19th century don’t need a pill to conk out at night.

Eugene came to like these simple, contrite people. They were good and honest and moral, worked like fucking dogs, and cared little about financial reward, unlike the money-grubbing cockbites who slapped this goddamn, see-through shithouse together.

Today, the workers were called to put a lock on the attic door, which to Winnie, didn’t seem odd any more. Nor did her husband’s raging outbursts, or his foul language. Now 73, Eugene was showing signs of dementia, she worried.

More often than not recently, she would find him wandering the house in the dead of night trying to find my way back home to Rock River, he would mumble as she guided him, catatonic, back to bed. During daylight, he became a magpie, repeating in monotone, some gibberish word she made out to be methihkwiwi or something–his new mantra of sorts.

This morning her husband had pored over his empty squares, fuming about the state of the world/the country/the state/the county/the town/the weather/politicians/society that had gone to hell, and shook his head in either disgust or disdain as he gripped his pencil in concentration. And then, when Gene broke the silence with his mantra of sorts that echoed off the ceiling, and then broke out in a giddy laughter, something in her faded memory click-clickety-clicked—me think me wee wee. . . could there be a weird connection?

3

Suzanne Beatrice Burg was born February 2, 1911, and was a gift from the angels, as noted by the Dallas City Weekly Review. A paddlefoot-tag-along to her four older sisters, she was the only one who outlived them all before she even turned three.

The roller coaster accident that claimed her siblings had brought a pall to the town that was still reeling over the sinking of the great ship Titanic that had claimed over 1,500 lives the year before. Locals began to talk about the toddler’s miraculous survival from drowning in amazement and pity. Some were calling her the Unsinkable Soobie Burg, a riff from Titanic survivor, Molly Brown.

As reported by the Review a week after that fatal July Fourth, it was neighbor Julius Barnes who was out feeding his goats when he suddenly heard the gaggle of girly delight turn to screams of terror:

“Then I looked down from the bluff towards the river and just seen ‘em little train cars flip up and go down,” is the way he described it in print. “By the time I got to the scene, it was too late to help any of the poor little souls trapped underneath--then seen the baby bobbing towards shore thinkin’ I might be able to save that ’un.”

Barnes told how, when he plucked her from the river, little Soobie seemed only affected by her sopping diaper, and babbled, “me tink me wee-wee.” “Me tink me wee-wee” quickly became the pitiful buzzword in gossip around town, wringing a bit of levity from a real life nightmare when laughter was verboten.

The Review reported that Louis and Clara Burg received mourners into Blackstone, but they did not attend the funeral or the burials on July 9. As best folks could recollect, they were never seen much in town after the accident, having closed the factory for good the following Monday. (It was rumored that Burg’s guilt was so heavy about building the leisure ride that killed his daughters that he never picked up another wrench the rest of his life.) Nannies and cooks filled the bill as nurturers, making sure Soobie was cared for and fed until she was shipped off to a Chicago boarding school when she turned 14.

Maybe it was survivor’s guilt, maybe it was just the sad, strange wonderment of what her sisters might have been like had they lived, maybe it was seeing her mother and father growing more crazy with age, but Suzanne rarely returned to her hometown. Her parents’ obituaries only mentioned her presence in passing. (Louis died of tuberculosis, a choking disease affecting the lungs, on September 12, 1922; his widow, Clara, died tragically four years later on Christmas Eve. A housekeeper found her pretzeled body at the foot of the grand staircase, splayed light from the Tiffany windows spotlighting her crumpled corpse as it lit her daughters’ little alabaster faces a decade and a half earlier. Oh! The twisted ways of fate!

Suzanne absorbed the city, and in May of 1929, just 18, she married a rich, young, self-made Chicago hotshot named Portlock who lost everything six months later in the stock market crash. They had one child together, a girl named Barbara Jean, Winnie’s mom, born soon afterwards.

The Unsinkable Soobie Burg, the only heir to the Burg fortune and needing cash now, tried to unload Blackstone, but during the Depression folks couldn’t afford the dirt surrounding the three-story edifice, especially in small-town mid-America where poverty and drought were really taking a toll on lives and crops. And who would want to start a factory when spending capital was scarce?

Her and hubby returned one last time to Dallas City to gut the place of its finest furnishings to sell piecemeal to various Chicago pawn shops, pennies to the dollar. The stuff held no sentimental value: no, quite the opposite--Suzanne only felt contempt for this place and for her parents who remained stuck in the summer of 1913, and anger at how she was forced to watch their pathetic vigilance waiting for the other girls to get home from school every day. Grief sucks--in their vain and hopeless delusions, Louis and Clara ignored their living daughter as if it was she who died.

That money went fast, gone mostly to bootleg booze in speakeasies about Chi-town, a little bit to satisfy the baby’s barest needs; while legal liquor got Soob through the 1930s. Her drinking only improved after 1942, when Corporal Portlock was blown to bits by a German mortar near Reims, France during World War II.

Barbara Jean, sick of her mother’s drunken rambling about how her sisters’ died while she lived, and then, at 11, being the emotional crutch for her widowed mom, moved out at 15, got pregnant at 16, and gave birth to daughter Winifred on April 10, 1947.

As indifferent to their progeny as were two generations of Burgs since 1913, Barbara was over-protective of little Winnie, helicoptering over her when she wasn’t trying to support them both. Things were getting tough in the city--veterans had come home from the butchery of the war and wanted their jobs back--Rosie the Riveter was nice and cute and thanks, but now get back in the bedroom and the kitchen where you belong--and because the returning heroes were marrying and starting families, rent prices in the city were skyrocketing.

What to do, where to go, came to her at her mother’s hospital bedside as she lay dying of pneumonia, a condition where fluids fill the lungs, similar to how dear old dad went out, and in a more morbid kind of way, like drowning, just like her sisters all those long years ago.

Suzanne, on oxygen, seemed at peace and back in time, recalling fondly now the quaint town across the state where she had come from. In times less lucid, she would call out to her sisters in a pique of coughing fits and gasping, asking if this is how they felt when they were fighting for their last breaths that Independence Day afternoon. She rejoined them, her sisters and parents, on October 16, just after 10 PM in spirit only. Her body was laid to rest in Chicago’s Mount Hope Cemetery, per her final request.

Four days later, Barbara Jean and three-year-old Winnie were on a one-way train ride to Quincy; then on the Doodlebug (a short line car) up to Dallas City. She had moved here for a new, simpler, cheaper life, sure, but also to redeem the reputation of the Burg family name, demeaned by decades of urban legends and tales of a haunted Blackstone.

She got hired on to bake pizzas, and found a house--an entire house--not a walk-up with four walls to rent that seemed almost free compared to her monthly dues in Chicago. Mother and daughter, back in town to close the Burg family circle, regularly visited her great-aunt’s graves in the town cemetery and peeked through the windows of the mansion that hadn’t yet been broken and boarded up, still empty after all these years.

Standing on the riverbank where her mother was rescued, Barbara Jean told her young daughter for the first--and only--time the “me tink me wee-wee” story that she had been told her a thousand boozed up times--baby talk phonetics that click-clickety-clicked only when Winnie Burg-Portlock-Rathbun turned old and gray.

4

The busy bees in straw hats and dripping in denim were just finishing up the attic job when the phone rang. Winnie took the call in the kitchen on the cordless, then conversed in the pantry because of the commotion the Amish were making. Calling was Charles McDonald, president of the Hancock County Historical Society.

“This is her,” she replied, drawing a deep anxious breath, missing not having a cord to fidget with when asked if Winifred Rathbun was available.

“Didn’t uncover any location or formal name regarding your inquiry about the phrase, me tink me wee wee, and I researched several sources,” McDonald responded. “Then I got to thinking phonetically–maybe it was an Indian language, so if I could figure out what people spoke it, I could figure out its meaning. I looked up different versions of the word, wanted to start with the local tribes, but had to drive down to the Quincy library to find translation dictionaries.”

“And?”

“And, yes, I got lucky and found the meaning,” he drawled, building up suspense.

“And?”

“It’s methihkwiwi…means hail is coming down, in Sauk, Mrs. Rathbun,” he said before the receiver grew quiet with a short intermission of silence. “You there, Mrs. Rathbun?”

“Yes, I’m here. Mmmmm…hail is coming down, huh?” she replied, noticeably disappointed. “Well shoot, that doesn’t tell me much. Must be a word my husband picked up from tv--either from watching documentaries on the History Channel or from the Burlington cable station he likes that airs only 1950s westerns and the embarrassing dialogue of white actors cast as natives speaking rudimentary English as if they were slow and stupid,” she whispered, more to herself than to the researcher at the other end of the phone line, some of Eugene’s cynicism rubbing off on her.

“Yep,” he agreed and cleared his throat. “So anyway, the story of your grandmother as baby Soobie Burg feeling bad because she wet her diaper seems to be just that. ‘Me tink me wee wee’ just plain old baby talk. Doesn’t seem like a connection with the word your husband seems to have taken a liking to. Personally, I think the two are mere coincidences.” She could hear his voice change back to that of an authoritative historian. “Anyway, I hope this helps, Mrs. Rathbun. Please feel free to contact me any time should you need more questions answered. Good day, Mrs. Rathbun.”

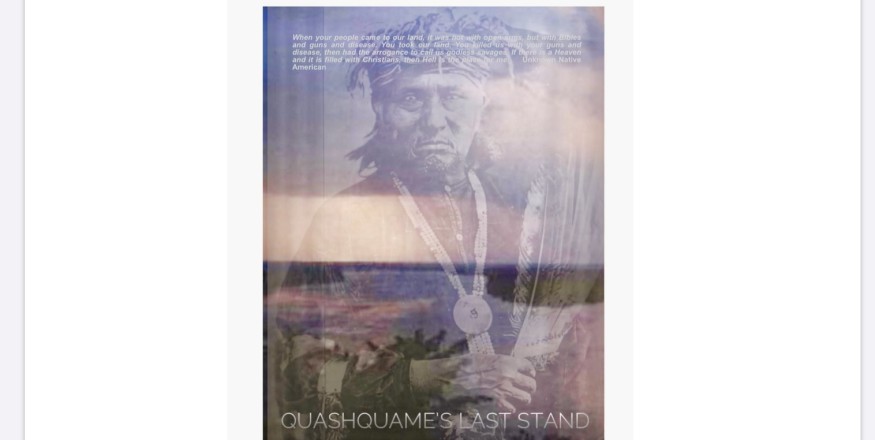

Winnie cradled the phone, paid the waiting workers in cash, then sipped her afternoon chamomile at the bay windows. She wasn’t so sure there wasn’t a connection. Hail is coming down…somehow a warning for all the crazy stuff with the house because Quashquame’s grave was desecrated?

She thought about Eugene’s deep slide from decency, his new Sauk mantra, the Burg dysfunction since July 4, 1913, and me tink me wee wee. Was it a warning--then and now--that tragedy is in the air? she wondered. Her staunch disbelief in ghosts and curses involving dead Indians was beginning to soften.

ns3.140.250.173da2