Eugene Rathbun loved teaching music at Dallas City High School in the imposing three-story stone edifice complete with bell tower and turrets, everyone called the Castle. Raised in Chicago with a degree from Northwestern and thinking nothing existed west of the city’s suburbs but cornstalks and old poops who liked watching paint dry, Eugene took his first job “out in the boondocks where the state poops out along the Mississippi River,” he joked to his friends and family, partly in jest; mostly in dejection. “I’ll be back in the city in a few years teaching at a real high school,” he promised.

That was 47 years ago.

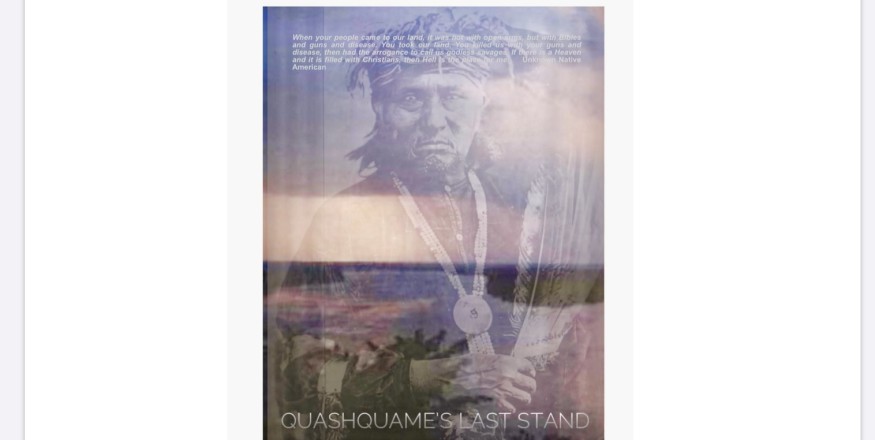

Although he initially felt like he had come to teach music on Mars, Eugene slowly became beguiled by this place so steeped in history and in natural beauty, and began to absorb the creative, intellectual—almost supernatural—energy that pulsated from the area: Hannibal, MO, where young Sam Clemens’ imagination flowed inside a clapboard house on Bird Street, was an hour south, downriver. Galesburg, Illinois, the boyhood prairie town of poet and biographer Carl Sandburg, was an hour east . . . through the cornstalks and old poops. An awkward, young attorney named Abraham Lincoln rode the judicial circuit here, learning law and oratory. (Sandburg came to write the definitive biography of Lincoln in 1939–his four-volume “War Years″ won the Pulitzer Prize for History a year later). Prophet Joseph Smith set up his Mormon community in Nauvoo, the next town over, until he was assassinated, his followers booted from the land and exiled into Iowa on their long, forced trek to the Great Salt Lake. Eugene was in the dark about the rural area being the natives’ last sliver of homeland a couple hundred years before, and their genocide and forced removal, as American abominations like that were written out of textbooks.

If not for this area’s heady early influence on these fertile young minds, the odds are favorable that there would have been no Gettysburg Address, Emancipation Proclamation, or bios of Lincoln’s life, because the 16th POTUS would have been someone else. Shoot, we might even be two countries right now if not for him; there may have been no Tom or Huck or even Mark Twain, for that matter; no 17-million-strong Church of the Latter Day Saints, he liked to ponder, for what that’s worth.

Eugene Rathbun especially became fixated by the view from the bluffs that rose 500 feet from the river valley below. From this lofty perch, he could get lost in the panoramic, unobstructed beauty of the land stretching out below him.

He strained to see Fort Madison, Iowa, a railroad town, tiny across the river, looking from up on high like one of those little train villages that are ubiquitous around the holidays. He loved it up here because he could let his imagination soar with the turkey buzzards: kites without strings, they were!

From up here, where the only sounds were insects and the wind, he could revel in the river’s many emotions: its placidity of summer sunsets mirrored on its smoldering surface; the sinking sun, a dragon’s breath lighting up the water as if it was gasoline; its muddy waves churned up by angry springtime storms–a tempting swim for Willie Wonka; its frozen bleakness with the few sapphire ribbons of open water offering sustenance for bald eagles, otherwise, she remaining cold and aloof ’til spring. Walking the bluffs became his peace and quiet away from the cacophony of nearly a hundred semesters of lower education band practices.

Steeped in the history of the region and feeling comfortable with his (mostly) well-behaved students and (mostly) involved parents, Eugene slowly lost his appeal for Chicago’s clamor and culture and began to embrace calm and contentment in a town just a few years past Mayberry. A town of honest church-going people who would kindly offer help when needed. A tight-knit community of patriotic farmers, factory workers, hunters and fishermen. A tidy little town where folks took pride in themselves, their homes, yards, and gardens. Marrying the town’s sweetest beauty sealed the deal.

2

Winifred Margurite Burg Portlock was the only child of the only child of the only surviving child of Louis Burg, the successful automobile maker and the builder of Blackstone, the family’s locally-quarried limestone mansion adorned with hand-carved native hardwoods and set with magnificent Tiffany windows. (It was whispered about town in awe that the furniture was so exquisitely crafted that Queen Victoria of England offered a million dollars for it so she could gift it to a duke, but Mr. Burg had turned down her offer.)

The stately home, architecturally a river reflection to the Castle, stood grandly in front of three factory buildings as if trying to hide their red-brick inferiority. (Eventually, time took two of them down; the third became a pizza-making factory/roller skating rink, Little Italy, then the regionally renowned Riverside Supper Club after that).

Growing up in Dallas City, and in small-town America generally, during the Fifties was the best of times. The town boasted three grocery stores all doing well, each with its loyal customers, and stores for jeans to jewelry lined the three blocks of Oak Street. The half dozen cafes were thronged by teenagers hanging out and playing pinball and drinking sodas and shakes or roller-skating across the second floor of Little Italy.

Two car dealers, both reputable members of United Methodist Church, on either end of town enjoyed the competition to sell rocket-inspired, eight-cylinder metal monsters that were selling like Moonpies after Sputnik; the many service stations were in a perpetual price war to see who could feed these thirsty, fossil-fuel-spewing-missiles-on-wheels with the lowest price of gas in town!

The only business on the ropes of this bustling little burg was the Rialto. Like all other local movie theaters across the country at the time, its silver screen had given way to tiny ones at home, displaying ghostly, black-and-white images lit by cathode tubes, mesmerizing millions.

The innocence of sock hops, white-bread pop singers crooning puppy-love lyrics for high school make-out sessions (heavy petting, at most) and shakes and skates was shattered when Oswald killed Kennedy. National optimism was also splattered in blood and brains that day in Dallas, turning a national youthful frivolity into adult seriousness. America was changing: Bobby Darin gave rise to Bob Dylan; segregation fell to the Equal Rights Amendment, signed by Democrat President Lyndon Johnson in 1965, despite strong resistance from anti-integration forces. Abortions were legalized by the United States Supreme Court in 1973.

The folks in Dallas City clung on. Sure, some of the kids went ga-ga over the Beatles and the Stones and the Kinks, a few braver high school boys even started sporting long hair despite the sissy jokes-but for the most part, they remained insulated from all the turmoil they witnessed each weekday evening in their half-hour spent with Walter Cronkite.

Drugs and commies seemed to be running rampant on college campuses by the look of the stoned-out hippies burning their draft cards and their bras shown on the nightly news, but so far the only anarchy coming into Dallas City seemed to be an occasional bag of ditch weed a college kid would bring back home to share with fellow alums. Let’s keep it that way, praise the Lord!

And then there was Vietnam, a war that divided the country as surely as the Civil War had done. Most supported the conflict, at least early on, and the town gave a grand solemn, patriotic public funeral when Private First Class Randall Samuel Simpson came home in a box, killed during heavy fighting near Con Thien in July, 1966.

The American Legion color guard and six uniformed veterans solemnly led Simpson’s star-spangled casket through the double metal doors of the Castle’s add-on gym, followed by veterans who made it back from their wars alive, followed by Dallas City Boy Scout Troop 104. The basketball court where Randy showed off a fairly decent jump shot became his catafalque. The bleachers were packed with mourners; the dias packed with praiseful eulogies about the brave young man who sacrificed his life for our freedom.

Private First Class Simpson, only 19, died a hero--the rumors around town about him sneaking into the girls’ locker room to pilfer their bras and panties during volleyball practice a year earlier, conveniently and patriotically, forgotten.

3

Winifred, known by all as Winnie, was an overachiever, feeling from an early age she had to vindicate the Burg family name: Bulldog cheerleader; straight-A student; Betty, of Archie comic book fame, popular in that era, made carnate; girl scout; Christian. She breezed through high school, unchallenged except for band--she wished that, of all things, playing the clarinet was as easy as calculus.

Her striving for musical perfection paid off, at least romantically. On July 4, 1967, (known as the Summer of Love in pop culture and Independence Day since 1776), and back in town from college, she spied her dusty clarinet case tucked away on a bottom bedroom shelf and decided to give it the old college (high school) try. The park would be nice. The river’s calm and it’s not too muggy yet, she thought. Her first few warm-up scales shooed away the Canada geese; after that she thought she sounded pretty good, even though the good-looking guy who was slowing down his car to listen seemed to disagree.

“Do you have a permit to play that thing in the city park, miss?” the driver sporting a porkpie hat asked with a false sense of Chicago bravado in his voice. “Because I think there’s a noise level ordinance in this town.” This was one of the few times in Eugene’s life where he felt brave and emboldened, odd as heck, as women, especially beautiful women such as this one, intimidated the crap out of him. “And you seem rather close to the noise ordinance level limit. But, please, don’t let me stop you!” He chuckled to ensure that his comment was to be taken in jest and urged her on.

Her reply was encouraging.

“My family used to own this town, sonny-boy, so shove the noise level ordinance up your—down my licorice stick!” Oh my! Did that sound suggestive? she wondered, then blushed, then laughed, then started the song again from the top, this time blowing the woodwind with marching band force.

Eugene poked his head and arms out the car window and feigned directing her. When she finished her sonata, he pulled over and parked so he could give her a standing ovation, and-oh! my gosh! is he actually doing this?-walked over to introduce himself.

“Bravo! Bravo!” he shouted over his own applause. “Baby Elephant Walk,” an instrumental written by Henry Mancini especially for the clarinet, for the 1962 film Hatari!” he stated matter-of-factly, “and a rousing rendition, I might add.”

“Thanks, sonny-boy. Who are you and why the trivia?”

“Hi. My name is Eugene Johnathan Rathbun and I’m the new high school music teacher, starting next fall,” he bragged confidently (where was that coming from?), “and you are just the gosh darn prettiest gal I’ve ever seen!” (did he really say that?). “How do you do”?

His lame pick-up line and her reciprocating clarinet serenade must have click-clickety-clicked, for a year later she became Mrs. Winnie Rathbun, dropped out of college, and returned to Dallas City to raise a family.

4

Now Eugene, in his almost half century of high notes, low notes, wrong notes, sharps and flats (some intentional), slimy spit valves, split reeds and lost sheet music, was ready to retire. He had conducted bands through stirring strains of John Phillip Souza marches (or as stirring as a small-town high school pep band can muster) and through reworked renditions of sometimes controversial rock songs. (His idea to perform the Clash’s Rock the Casbah at the winter concert back in ’06 might not have been his finest hour when a few concerned parents complained that the word casbah opened up fresh wounds from 9/11. Them Muslims tried to bring their Sharia law here to destroy our freedoms!!! a letter in the Dallas City Weekly Review read. NEVER FORGET, Mr. Rathbun!)

He and his bride had lived a good, full, rather inauspicious life; their only heartbreak that she miscarried in her first month of pregnancy, twice, had faded like a diminished chord. The family they had dreamed about and planned for did not happen. There were no kids to inherit what they had worked for, so why not retire? Shoot, he would receive a full state pension and could rest comfortably after socking away most of his pay all those years for the proverbial rainy day that, thank God, never came.

Darn it! Eugene and Winnie Rathbun decided he would call it quits and do it in style by building a brand new house on the outskirts of town! And he knew exactly where it was to be built—his walking sanctuary on the bluff. The LOT FOR SALE sign came down, their promise for a happy retirement keyed up an octave.

It was as if fate itself had smiled upon the Rathbuns that this undeveloped parcel of land outside the city limits had just become available for development. In quick order, the property was deeded, the blueprints for the double A-frame (designed from a dream Eugene had to mimic twin teepees) were mechanically drawn, the perimeter staked out with little orange flags.

5

November 3, 1991, marked the beginning of the end when the Rathbuns’ dream home took shape. Eugene drove up the bluff after his last class before lunch to meet the excavator who was scheduled to be there earlier that morning but was a little late finishing another job. He was not complaining (Eugene was the type who never complained), for now he could enjoy the ground being broken and the foundation being dug, and not have to be back at the Castle until school let out. Then it was marching band practice for the homecoming parade on Friday, his last, and rehearsal for the halftime show during the football game pitting the Bulldogs versus arch rivals from the county seat, the Blue Boys.

Waiting anxiously in his car with Queen’s, We Will Rock You, the ubiquitous sports anthem played at every DCHS sporting event during the last decade still roiling through his brain, Eugene watched the little orange flags outlining his new digs snap, seemingly angry, in today’s raw wind. He shivered and turned on NPR and half-listened to two opposing senators debating a first-ever trade agreement between the US, Canada and Mexico that was starting to be kicked around Congress. One senator was calmly touting the deal as a great business boon for all Americans; the other was not so sure.

6

The impetus for a free trade zone began with United States President Ronald Reagan, who made the idea part of his campaign when he announced his candidacy for presidency in November 1979. In 1988, the Canada-United States Trade Agreement (FTA) was signed; shortly afterward Mexican president Carlos Salinas de Gortari proposed a similar agreement in an effort to bring foreign investment into his impoverished country to U. S. president George H. W. Bush. As the two leaders began negotiating, the Canadian government under Prime Minister Brian Mulroney feared the advantages Canada had gained through the FTA would be undermined by a US-Mexican agreement, and asked to become a party to the talks.

Following diplomatic negotiations dating back to early 1990, the leaders of the three nations signed the agreement in their respective capitals in December 1992. President Bill Clinton signed the bill into law a year later, on December 8, 1993. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was created to eliminate tariff barriers to agricultural, manufacturing, and service; to remove investment restrictions; and to protect intellectual property rights. This was to be done while also addressing environmental and labor concerns.

The effects of the agreement regarding issues such as employment, the environment, and economic growth were, and remain, controversial. According to a 2011 article by EPI economist Robert Scott, nearly 700,000 U. S. jobs (mostly from the manufacturing sector) were lost or displaced as a result of the three-country deal; according to the Sierra Club, NAFTA contributed to large-scale, export-oriented farming, which led to the increased use of fossil fuels, pesticides, and GMOs (genetically modified organisms). In their May 24, 2017, report, the Congressional Research Service wrote that the economic impact of NAFTA on the U.S. economy was modest, primarily because trade with the other two countries accounts for a small percentage of its gross domestic product.

7

“Blah, blah, blah! Who gives a hoot. I’m soon to be retired!”

Eugene flicked off the radio and chuckled to himself as the wind buffeted the car like the river would a jon boat down below. The pitch and rolling of the older model, low-mileage Buick (buying a new car was a big decision and Eugene hated making big decisions; besides, they never really went anywhere) combined with what was probably the beginning of another head cold (as anybody in the profession knows, educators fight off viruses from September to March. It comes with the territory) was starting to make him dizzy, almost seasick.

Chilled, he put on his lucky porkpie hat that he had worn while driving the width of the state for the first time, the day he met his wife, and at their wedding reception that was celebrated at the town’s VFW banquet hall on 4th Street, next door to the volunteer fire department shed and catty-corner from Sacred Heart Catholic Church. Today was another lucky day.

Eugene ignored the touch of nausea and got lost in the day from up here: autumn smells like a library, if books were printed in chlorophyll, he thought to himself, drawing a deep breath. Today, the landscape was anything but placid, first indicated by the snapping little orange flags. Leaves from the trees that anchored on the islands were dappled bits of flying, flaming yellow, gold, crimson and scarlet, looking like they were forced from a confetti cannon. Green daubs of vegetation, fighting to remain relevant, blended with dabs and splashes of sienna, umber, and yellow ocher where the sun hit right; jagged trees and sky reflected from the broken-mirror effect of the agitated water. His mind’s eye equated the scene with the crescendo of a symphonic piece, for nature is simply music that we can see, he mused.

His flight-of-fancy took pause when Eugene saw the tell-tale banner of diesel smoke belching black and blue from the grader bellowing up the gravel trail, kicking up dust, roaring loudly--a mechanical glutton ready to gorge on 10,000-year-old soil. He could feel the ground weirdly vibrate and rumble from the steel behemoth, perhaps like the natives felt in the days when the railroads were first going through. What a thought to flash on, he thought for a second, then dismissed the feeling with joy. What a relief to get the foundation dug before the winter ground froze! They could begin construction very, very soon, by golly! Hallelujah!

He got out of the Buick and did a pretty fair happy dance, considering his arthritic knees and the head cold he was fighting off.

“Hey, Mr. Rathbun. Howya doin’?” the operator asked.

Dicky Peterson, class of ’79, fifth seat trumpet (he tried!), always liked his big-boy toys. In high school, he dragged the length of Oak in his hunter-green Plymouth Roadrunner, cherried with a four-on-the-floor transmission and racing-slick tires, and was always fascinated by big machines. After graduation, he was beyond jazzed to be hired at a unionized backhoe manufacturer in nearby Burlington, Iowa. Big machines. Big money. Enough to buy his own heavy equipment and do some excavations on the side.

“I’m excited as all heck!” Eugene replied. “How long do you think it will take to get the foundation scraped down?”

“Be dug out by dark, easy, once we get goin’,” he replied. Then, looking out over the bluff, gushed, “this is a great place for your new house. You got it made. You’re really quite lucky, Mr Rathbun!”

Eugene’s excitement was dampened by his ex-student’s unpleasant, unexpected reply--did Dicky Peterson just yell to him, “you’re really quite fucked, Mr. Rathbun?” Did he really use such an ugly swear word? And why the weird muffled voice, Dicky? he wondered before remembering his growing head cold and dizziness, and how words can be distorted by the wind. So, he dismissed the answer as that, and got excited again as he watched the mechanical straight-edge shave off the first few feet of topsoil laid down during the last Ice Age. Then another. And another.

The groundwork was going as planned until Dicky Peterson brought up something more than dirt--caught in the behemoth’s iron jaws were some very tattered, faded fragments of woven cloth in designs of once beautiful color and bones that proved to be human. The digging was halted until spring for the required archeological excavation.

ns3.15.221.46da2