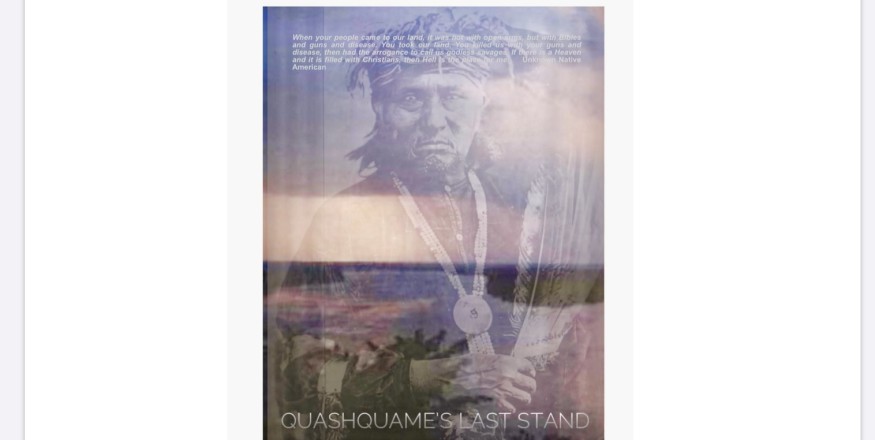

Quashquame knew the river well as it watersnaked from “northern Missouri up to southern Wisconsin,” the ancestral homeland of his people. He could never have imagined when he plied the arterial waterway as a boy that it would ever have come to this: that the light-skinned usurpers would swarm upon their land like insects, take it, and then add their stolen land with other light-skinned usurpers’ stolen lands and called them “states,” which in turn were knit into a much larger and more powerful territory the whites call “the United States.”

The very idea that the land could be bought and sold, platted and owned was as ludicrous an abstraction to the old Sac chief as not knowing that the soil itself was merely a cloak, like a rabbit‘s skin, a thin integument not covering flesh, but a solid sphere of rock hurtling through space.

He could have never guessed when he was a boy that the land theft and banishment of his people would be set in motion—all because of his foolish and fateful mistake made back in the long-ago year of 1804. Or of the subsequent massacre and removal of his people in the following decade. Or that his bones were going to be dug up nearly two centuries later, forcing his spirit back into this reality.

Quashquame prepped his canoe in front of the fort that was reconstructed in the 1970s, the early morning mist nearly as thick as the turbid water the whites call the Mississippi. The river was mostly liquid now, but still frigid and patchy with ice; the pre-dawn fog swirling dark and heavy enveloped the faux military post like a shroud, reminding him of what was lost all those years ago.

His weathered face betrayed a guilt-eaten sadness in the languid morning as he gazed up at the limestone bluffs on the Illinois side, the staging ground where the soldiers slaughtered, then removed, his still-alive surrendered people—an act made legal by his signing of The Treaty of St Louis, on November 3, 1804, concluded by William Henry Harrison on behalf of the United States of America and him and three other Sauk chiefs. The swindle transferred a huge area of land along the Mississippi to the United States. In return, the tribes received a lump-sum payment of $2234.50 and an annuity of $1000. It marked the beginning of the end.

He recalled in shame his friend Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak (Black Hawk) who disputed the deal, declaring that: “Quashquame was not authorized to sign treaties; that he had come to the gathering about a different dispute and was not expecting to negotiate land deals. That they appeared to be drunk the greater part of the time while at St. Louis.” Black Hawk bitterly rejected the exchange by saying, “I will leave it to the people of the United States to say if our nation was properly represented in this treaty? Or whether we received a fair compensation for the extent of country ceded by these four individuals.”

Quashquame had been interred over there, too, in spite: the funerary rituals prepared in haste and with malice; his wizened corpse wrapped in a blanket woven in designs of beautiful color and laid in a rough coffin in a sitting position; around his neck, his string of beads; on his head, his turban of braided cloth; around him, a jug of water, bowls of food, and his fan of eagle feathers that provided for his journey in a land of which this one was but a shadow. His detested remains were smuggled across the river and buried on the same bluff that was used as an Sauk shooting-gallery back in the day, then forgotten by history. Revenge has many fangs.

Quashquame now bared a chilly smile as he silently, stealthily, pushed off from shore, phasing in and out, paddling towards the streaks of orange, pink, and saffron that were waking up the eastern sky, knowing he would never come this way again. He looked back one last time at a fading Fort Madison, and then forward to the first town ahead, the cause of his resurrection.

“Ha! A chance to right the wrongs! Methihkwiwi!” he shouted, causing the early birds carousing on the water to take flight, and set out on his mission of revenge.

200 years before, he and his people had a fleeting moment of hope of restoring what they once had, of redeeming his mistake. On September 5, 1812, a group of Sacs and Foxes attacked the fort, killing and scalping a soldier who was caught outside the stockade on his way to the latrine. They shot burning arrows inside the confines, slaughtered the livestock, and destroyed crops.

In July 1813, their relentless attacks on the troops of their United States led to a siege of the outpost that was so successful that the soldiers’ bodies they killed could not be recovered, nor could those left alive leave the confines to even collect firewood. The soldiers were on the verge of starvation. The incessant war hoops night and day kept them edgy.

On the evening of September 3, 1813, US army men crept on their hands and knees through a 100-yard trench dug to the river and abandoned Fort Madison in flatboats. One remained behind a moment to torch it to the ground. For a long time afterwards the Indians called the spot Po-to-wo-noc, meaning Place of Fire. River men spoke of the burned-out remains as Lone Chimney.

Black Hawk observed the ruins soon afterwards, gloating that “we started in canoes, and descended the Mississippi, until we arrived near the place where Fort Madison stood. It had been abandoned and burned by the whites, and nothing remained but the chimneys. We were pleased to see that the white people had retired from the country.”

As if.

ns18.117.231.165da2