Fools, because of their rebellious way, and because of their iniquities, were afflicted.

Psalm 107: 17

THEY TOLD HER SHE would die here. This place that she did not know, this dark, dank, rancid dungeon where nobody wished her well and most spoke languages alien to her....this place she would call home for the rest of her life. That's what they told her. It was getting harder to disbelieve them.

There were people in there who wanted her dead, some in retribution but most to establish their own notoriety. It would be a sure path to fame to kill her or one of her friends, known collectively as the Monte Carlo Actress Killers. That was the moniker that stuck in the international media. More imaginative than the Gang of Four, the Falling Stars, the Desperate Glamor Gals. Less chilling, to her at least, than the one that ran on the front page of Le Monde the day after the verdict: Poupees Cassees.

Broken Dolls.

So she waited. For a miracle. For newly discovered evidence. A confession from the real killer. A sympathetic ear to her appeal. Or just the morning when she'd wake up and discover this was all a dream. The last three-hundred-and-ninety-eight mornings, she'd opened her eyes and prayed that she was back in Hollywood, or, better yet, back in Hammersmith, London, England, her birthplace, studying more acting for the entertainment-starved American masses.

And she watched. She turned every corner widely and slowly. She kept sitting up. She tried to avoid any routine that would make her movements predictable, that would make her vulnerable. If they were going to get her in here, they were going to have to do it the hard way!

It began as a normal day like any other. She walked down the narrow corridor of H Wing. When she approached the block letters on the door's glass window----INFIRMERIE---she stopped and made sure her toes lined up with the peeling red tape on the floor that served as a marker, a stop sign before entering.

"Bonjour," she said to the guard at the station on the other side of the hydraulic door, a woman named Henriette. No last names. None of the prison staff was permitted to reveal anything more to the prisoners than their first names, and those were probably false, too. The point was anonymity outside these walls: because of it, the inmates, once released, wouldn't be able to hunt down the prison guards who hadn't treated them so nicely.

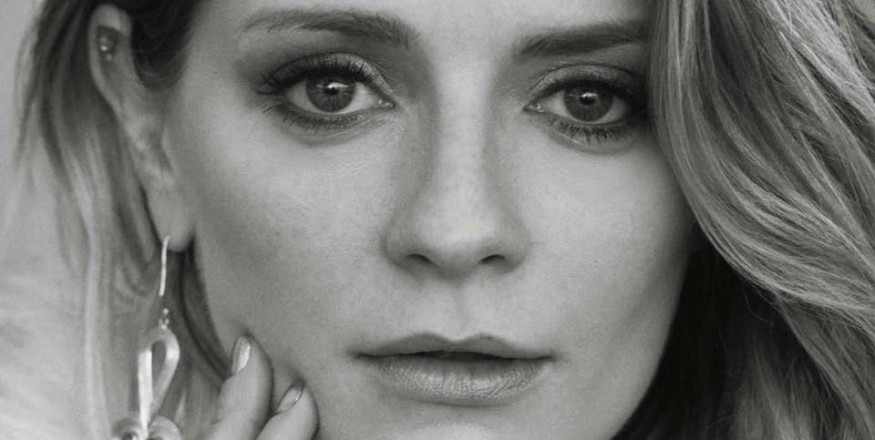

"Hi, Mischa." Henriette always greeted Mischa in her best English, which wasn't bad. Better than Mischa's French. After a loud, echoing buzz, the door released with a hiss.

The prison infirmary was the length and width of an American gymnasium, but it had a lower ceiling, about eight feet high. It was mostly one open space filled without about two dozen beds. On one side was a long cage---the "reception" area-----where inmates waited their turn to be treated. On another side, also closed off and secured, was a room containing medical supplies and pharmaceuticals. Beyond this room was a high-security area that could hold five patients, reserved for those who had communicable diseases, those in intensive care, and those who posed security risks.

Mischa liked the infirmary because of the strong lighting, which lent some vibrancy to my otherwise dreary confinement. She liked helping people, too; it reminded her that she was still human, that she still had a purpose. And she liked it because she didn't have to watch my back in here.

She disliked everything else about it, unfortunately. The smell, for one thing---a horrible cocktail of body odor and urine and powerful disinfectant that always bowled me over when I first walked in. And, well, fuck, nobody who comes to the infirmary is having a good day.

She tried to have good days. She tried very hard.

It was busy when she walked in, the beds at full capacity, the one doctor, two nurses, and four inmates who served as nurse's assistants scurrying from patient to patient, putting figurative Band-Aids on gaping wounds. There'd been a flu going around, and at JRF, when one person got the flue, the whole cell block got it. They tried to segregate the sick ones but it was like rearranging chairs in a closet. There just wasn't much room. JRF---L'Institution de Justice et Reforme pour les Femmes----operated at more than 150% capacity. Cells designed for four held seven, the extra three people sleeping on the floor. A prison intended for twelve hundred was housing almost two thousand. They were packing them in like sardines and telling them to cover our mouths when they coughed.

Mischa saw Rihanna at the far end, wrapping a bandage on an Arab woman's foot. Rhi, like her, was a nurse's assistant. The warden ordered that they not communicate, so they were assigned to different cell blocks and different shifts in the infirmary.

She felt a catch in her throat, as she did every time she saw her now. Rhianna had been my closest friend since she relocated (temporarily) to Salzburg to be with her boyfriend. They'd been living next door to each other for the past five years, sharing each other's secrets.

Well, not all their secrets, it turned out. But she'd forgiven her.

"Hey." Rhianna whispered in her lovely Caribbean accent. Her fingers touched Mischa's. "I heard what happened. You okay?"

"Living the dream," I said. "You?"

She wasn't in the mood for humor. Rihanna was a stunning beauty---tall and shapely with large radiant eyes, chiseled cheekbones, and silky, ink-color hair--which made it all the harder to see the wear around those eyes, the stoop in her posture, the subtle deterioration of the spirit that made her the idol of millions. It had been just over a year since the murders, and three months since the conviction. She was starting to break down, to give in. They talked in here about the moment when that happened, when you lost all hope. La Reddition, they called it. Surrender. Mischa, herself, hadn't experienced it yet and she hoped she never would.

"Movie night," Rihanna whispered. "I'll save you a seat. Love you."

"Love you back. Get some rest." Their fingertips released. Her shift was over.

***********

About an hour and a half later, Mischa heard the commotion as the hydraulic door buzzed open. She had my back turned to the entrance. She'd been helping a nurse dress a laceration on an inmate's rib cage when one of the other nurses shouted, "Urgence!"

Emergency. They had a lot of those. They had a suicide a week in JRF. Violence and sanitation-related illnesses had been through the roof with the worsening overcrowding. It was impossible to work a six-hour shift without hearing urgence called at least once.

Still, she turned, as guards and a nurse wheeled in an inmate on a gurney.

"Oh, God, no." Mischa dropped the gauze pads she'd been holding. She started running before the realization had fully formed in her head. The shock of black hair hanging below the gurney. The look on the face of one of the nurses, who had turned back from the commotion to look at her, to see if it had registered with her who the new patient was. Everyone knew the four of them as a group, after all.

"Rhi," she whispered.

Login with Facebook

Login with Facebook