Chapter 6 (A gilded cage)

Harry was back on the bottle; the verbal abuse would start from morning to night. He knew as I knew, I was alone in the world now. My grandfather had passed away.

I bit my tongue, and I allowed it to continue. I wrote to the church, but he intercepted those letters. He ruled, and I obeyed. He never punched me again, a throttle now and then. I lived with it. I had to.

Things changed the day he placed a baby in my arms and told me to raise it.

I didn’t ask questions. This little being changed my life, the verbal abuse I shrugged off, it was now part of my daily life. But the baby, changed my life. I knew I could be anything the day I held him.

Harry named him Henry Atkinson. I was as happy as a pig in well crap.

Henry changed everything. I had someone that depended on me, someone I knew loved me, didn’t judge me. A child does not see colour, creed or ones standing in the community. A child strived on love. I loved him dearly.

I raised him as I was raised, with a few grey areas. I needed him to see the world as I did. He was a beautiful baby, loving and such a good baby.

I found my voice again. Henry taught me, that I could be anything as long as I believed in it. I put my foot down. I would raise Henry, not Harry. The abuse didn’t change. However, he came to my bed less and less, it didn’t alleviate my fear of Harry. It made me fear him more, not knowing is by far worse. I couldn’t tell when he would snap. I was in a grip of constant anxiety.

A routine check-up, made my worst fears come true. I had an inoperable illness, one that was killing me slowly. I tried with all my might to hold on for Henry, time, and the lack of treatment had me bedridden.

Henry was old enough now to know that I was dying. He was a remarkable young man; I was very proud of him.

I dear say, dying changed my life, yet again. I think the burden on Harry was too much for him to bare, and he rewarded me with my freedom.

I was ready to leave this world. I had loved, and I had lost. I was ready, but that was not written in my starts. No I was brought back to life.

The day you are told you are going to die, you change your perspective on life, but the day you are told, you have borrowed time, you really start living, because every minute is precious.

I received an inheritance from my father and my grandfather. The farm was left to me.

When I was discharged. I went home. Another family had moved in next to my house. I no longer felt alone. The need to live, forced me to become stronger. I was a difficult few months, I got through it, because I had a reason to live.

I hired labourers. Not slaves. I forced my body to clean my own house. Each day I was a little stronger. I never fully recovered, I am still sickly, some days are just worse than the next. I still carry on, because I have a reason to live. I haven’t quite completed my circle. I was free, things around me were changing. People were evolving.

The day I knew I could stand, really stand on my own two feet I went searching for Inkosi. If all it took was to look at him one more time, my circle would be complete.

It still amazes me how time can fly by without one noticing. When I saw Funani again, he was a young man. An adolescent, and fluent in English. Mama had passed on. I think I had my fill of death, I knew then, I had not lived. I needed to live before I died.

Funani told me Inkosi had moved away to the Great Mountain. At first I glanced up at the blue mountains, he shook his head no.

“The Drakensberg?” uKhalamba in Zulu.

“Why? Why did he go so far from here?”

“He said he needed to see the world. Cities. He wanted to work in the city.”

I was gobsmacked. “I never knew that. Do you speak with him?”

“Yes, Madame. We write letters to each other.”

“May I have his address please?”

Funani walked back to his hut, and wrote down the address for me. “Ngiyabonga.” He smiled, and the likeness between him and Inkosi slammed right into my heart.

I sat down and wrote the longest letter of my life. How long it would take to reach him, I couldn’t tell. It was a weight off my heart, knowing he was alive and well. I know we change, I could never imagine him, in a suit. Without his dear skins. I tried to form a picture in my head to no avail.

I had written the telephone number down. I think I looked at it a dozen times a day.

No one called anymore, so I knew if it rang, it would be Inkosi.

A month passed, I had to learn fast, how to maintain a farm. I read books, spoke to my neighbours. A man came to my aid, not a white man. A brown man, my neighbour.

He was different, to anyone I have ever met. I was aware that his forefathers arrived here in eighteen-sixty, which laid the foundation for the Indian community today.

I also know, they did not come here willingly.

Arjun Puranam was Tamil. I had no idea what that meant at the time. He taught me. I guess I needed to understand, just as I needed to understand Inkosi.

I didn’t know whether Inkosi had a surname. I never asked.

Arjun fasted, most of the week. When I cooked and offered him food, he would explain to me why he didn’t eat meat. As time went my respect for him grew in leaps and bounds.

Inkosi did phone me. So much time had changed both of us. He was married, he had another son he named Sifiso, it meant ‘wish’.

He called me once, and never again. Arjun never asked me about my past, I was the one asking all the questions.

It was months later when he asked me to come into his house. He showed me where he prayed. He explained whom his Deities were, and what each did for him, and why he fasted on specific days.

I have pushed against everything, if my father was alive, I think he would have had me committed.

I wanted to understand, I was too old to be rebellious. Times were changing, I had changed, my love for Inkosi would never die, but I fell in love.

I fought it for the longest time. I had to, I was honestly playing with fire. Yet I understood Arjun in ways I didn’t understand Inkosi.

Intermarriages weren’t uncommon. It was just kept under a lid.

I have to admit, I was afraid, I was afraid I would lose Henry and Funani, if I allowed my heart to dictate my future. My religion, was a factor, I never thought about that in the years with Inkosi, religion wasn’t a factor.

I became ill, as I said prior I had spells of bad health, ever since I left the hospital.

My chest was very sensitive, I had pneumonia, in layman’s terms, inflammation of the lungs with congestion.

Years back when I attended Boarding school, I had felt ill waiting to enter the classroom. He told the girl in front of me, that I couldn’t breathe. The teacher thought I was faking, but I collapsed.

It was determined by a physician that my lungs had collapsed. I was on the brink of death.

Arjun’s mother nursed me. The fevers racked at my body. My past became intertwined with my current life, I couldn’t tell the two apart. I think I might have called Arjun, Inkosi a dozen times. I saw him and Sheba, when I opened my eyes.

I don’t know how long it took for me to recover. When I was lucid Arjun would ask me, who Inkosi was. I told him my version of the truth, that Inkosi was my best friend.

When I was walking around again, I noticed subtle changes in Arjun. He seemed distant. He helped me with the farm. It had rained for a long time. Too long, the river flooded, homes were washed away. And the crops were rotting before my eyes.

No one could work. I guess Inkosi was right, his forefathers had shown me their wrath.

I was beaten once again. I had to sell. And I did, a lady living alone, was severely frowned upon. Worse so than one in love with a bantu.

I don’t know who bought the farm, I received my cheque via a solicitor. I now live in a small town near the Drakensberg. I have been living here for about two years now, the winters are cold, but not as cold as England.

I taught in a little rural-school, I had obtained my teaching certificate. Arjun and I speak over the phone once a month, I don’t ask about the farm. It hurts like hell.

Apartheid was abolished. Mama Nandi was right all along, the faces before me are, Xhosa, Zulu, Indian and white. I teach the pre-school children.

I overheard a Xhosa boy fighting with another boy.

On hot days we took the tables and chairs outside. The sink-roofs will melt the skin off a cat.

The smaller boy was crying, I scolded the older boy, and picked the little one up.

I looked down at the tear stained face. “Ubani igama lakho?”

“Sifiso.”

Time stood still, I placed the toddler on the ground and I asked one of the other teachers to watch my class, till the bell rang.

I walked down to the stream, I pulled off my shoes and my stockings and I sat in the stream and I sobbed. Yes, one can say many boys are named Sifiso, but not ones that look so familiar. I grew up with his father. I was only three months old when I first arrived at the farm.

I waited until the bell rang, then I did a terrible thing, I followed Sifiso home.

The house seemed so quiet, I hid behind a tree. And Elderly lady opened the door for the little one.

I heard the voice behind me, but I only looked up at the sky. I willed my lungs to breathe.

“You do know Madame; I can report you for loitering.”

“I see.”

He could never hear his foot fall, I could feel he had stepped closer. He removed my sunhat, and let my hair cascade down my back. The feeling of his fingers against my neck turned my legs to jelly.

“No, you don’t see, you never did. One as stubborn, and spoilt, as yourself, she doesn’t see. I think age, wisdom and time might have cured her.”

He touched my shoulders and turned me around.

I looked up at his face. “My God, but you are beautiful.”

We stood like that for a while. Then we laughed, I have no idea why we laughed, even years back, we could laugh on cue.

“You need to eat Madame; you are too thin.”

“You do know I find that word offensive, and whom are you to tell me what I should do, sir?”

He lifted an eyebrow, he was dressed in long slacks, a button shirt, formal shoes, but around his writs were the deer straps.

“Well as it turns out I am your Principal. Miss Atkinson.”

I think I stepped back. “You are the headmaster of the school, why haven’t I seen you?”

“Funani is at college, he told me about the brown man, I guess I wanted to be sure, before I spoke to you, I know you have your moral compass, and I shall never again infringe on it. Not until you ask me to.”

“I am not married, not to Harry and definitely not to Arjun, I never laid with him, neither did I kiss him. He helped when the farm went under. I need to go back. I don’t know why, but I do need to go back, to walk between the sugar cane, too walk in the river, and to see my home. I know it’s abandoned now, and I know the land belongs to a Zulu, nothing could bring me greater joy, but I need to go home.”

He stepped closer, he no longer had the scent of homemade soap, no Inkosi had cologne on.

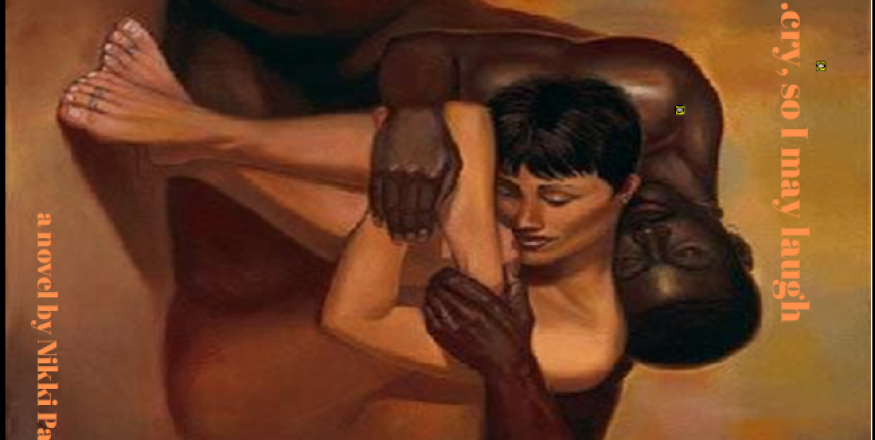

He took my face in his hands and he kissed me, I pulled him closer and wrapped my arms around him. I don’t know when we came up for air. He smiled at me.

“You have improved.”

“Oh bloody hell, really? You are the louse that taught me how to kiss.”

He laughed. “I did a terrible job; you really can’t kiss at all.” I mock punched him, but he grabbed my hands and held it over his heart.

“I am home.” I looked into his eyes, and I sobbed, he held me, I drenched his shirt with my tears.

“I am home.” He wiped my face.

“I’ll take you to the farm. This weekend. If that’s what you wish, I can do that for you, if you tell me one thing, only one condition.”

“Very well, ask. Are you asking as my Principal or my Chief? I need to clarify it first.’

“Neither, I am asking as your lover.” I blushed to high heaven, and he laughed at me.

ns 15.158.61.23da2